The Brief

Read ‘Rhetoric of the Image’ (Barthes, 1964) and write a reflection in your learninglog.

- How does Barthes define anchorage and relay?

- What is the difference between them?

- Can you come up with some examples of each?

- How might this help your own creative approaches to working with text and image?

The Essay

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen this essay by French philosopher Roland Barthes, published in 1964. The ideas of signifiers and signified, denotation and connotation were introduced when we were reading images in Context and Narrative [1]. Barthes sought to ‘spectrally analyse’ an image using the same structuralism ideas reserved for language. Barthes begins by writing about how linguists tend not to recognise ‘languages’ that don’t follow the structures originally theorised by Sausurre in the early 20th Century, citing the way that animals such as bees communicate with each other. Barthes wanted to see if images, also considered by some to hold little in terms of expression in language, could be read using the same principles of linguistics. As an example, he chose an advertisement for a French brand of ‘Italian’ food products called Panzani; this was what we looked at in our introduction to semiotics in Context and Narrative. Within the advertisement, Barthes identifies three messages; the linguistic which takes the form of the textual elements and captioning, the coded-iconic which is that which we visually read within the constructs of culture, and the non-coded; the elements in that are left. He treats the former separate from the latter two, arguing that the separation of them would serve no purpose. It is when he looks at the linguistic message, the idea of anchorage and relay are discussed.

Anchorage is the name given to text that seeks to answer the question ‘what is it?’ as Barthes explains, to limit or contain the element of uncertainty that the image creates. Although not explicitly used to describe what is in the picture, an anchor should be clear enough to restrict the creation of multiple narratives about either the whole image or parts of it. The anchor doesn’t only refer to the denoted elements that the image contains, but also the connoted which means that interpretation is also restricted. In his essay, Barthes uses an example of an advertisement or D’Arcy Preserves where some scattered fruit is included in the image alongside the caption “As if from your garden”. This anchors the viewer to a particular item (the fruit) but also the idea that the preserve is made from good things (the reference to the garden). When I read this part of the essay, I was reminded of the Lurpak advertisement that I looked at in Exercise 1 [2]. In that case, the caption read ‘Empires were never built on muesli bars’, which doesn’t refer to any single element within the accompanying image, but stops us from believing that the food being represented was the stereotype of a ‘health food’. This text anchors in the same way as Barthes’ example. He goes on to say that the use of anchorage to promote but also reject a particular part of the image or a narrative resulting from it, is the most common use of text with imagery.

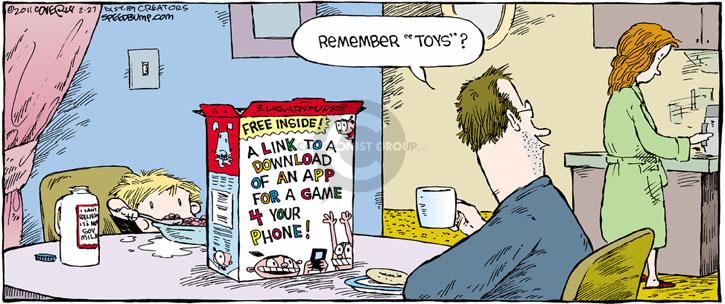

The relay is introduced as a less frequently used application of text to an image. Relay text is used to complement the elements in the image in a way that doesn’t describe them specifically but works with them to carry a narrative. The most common use of relay is in film where it supports the sequential building of a story by adding something about the subject that the viewer is watching. Barthes refers to comic strips as being good example of relay in action. Each comic frame contains as picture of characters set in the context of some action. The relay text guides the viewer to the story either by setting the scene or by being the dialogue between characters. Barthes points out that when relay is used effectively, the image becomes almost secondary in the reading of the story. See the example below:-

In this example, the text on the cereal box sets the scene of the frame. The speech bubble tells the story and the image shows a weary couple with a young child having breakfast. The image takes very little time to consume as a viewer as we are guided by the inclusion of the linguistic message (relay) and therefore don’t need to dwell on the iconic meaning of the image. Barthes makes the point that the idea behind a comic is that they are intended for people to consume quickly and rely heavily on the viewer bringing their own knowledge, both in terms of a code (language) to interpret the text, and in this example, about the current status of technology in our lives. Relay is not constant, as Barthes points out, it’s impact is felt differently depending on a number of social factors. With his Panzani example, the idea of Italianicity created by the text would only really be relatable to someone who wasn’t Italian. The use of the French language naturally puts the advert in the context of a French tourist who has some perception of Italian culture; they would have a different reaction to the linguistic message. In the example above, people of my generation would see the humour in the words spoken by the man, where children may not.

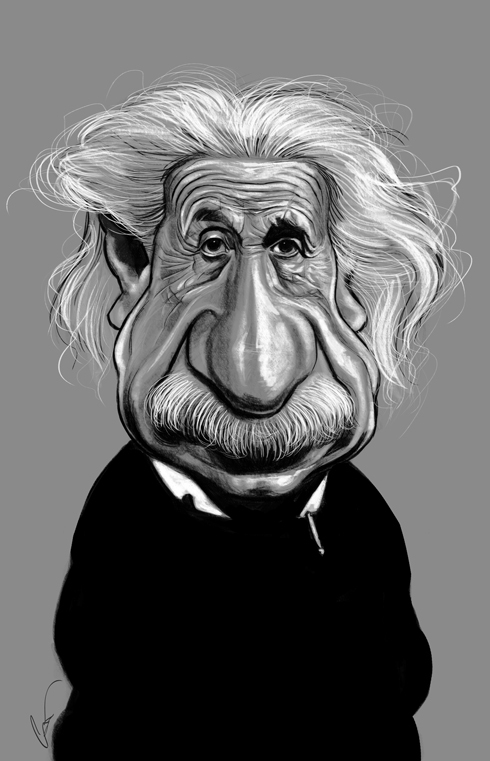

Barthes continues to explain that while images can be read using linguistic tools, photographs differ from drawings or paintings in that they contain uncoded iconic messages. What he means by this is that when a drawing is created, the representation of the subject is coded by the artist’s perception and knowledge, which is then read by the viewer. The representation doesn’t contain all information to signify the subject, but neither does the viewer necessarily need that to interpret it. In the most extreme case of caricature, the artist leaves some aspects out and exaggerates others, but we still know who the portrait subject is. Take this example.

We instantly recognise this as being Albert Einstein even though his famously wild hair, nose and moustache have been greatly exaggerated. The image is a likeness but not an accurate facsimile of the person it’s supposed to represent. Barthes argued that any image created by an artist has a code and in most cases, photography is the same. However, it is possible for photography to produce an image that is non-coded, i.e a straight copy of what is in front of the camera. The point Barthes was making was the even a non-coded image has information contained within, so if an extraterrestrial was presented with a photograph of what we know to be a tomato, they would not know a tomato but still see a shape and perhaps a difference in tone or colour. If we believe we can have an image with no code, the idea that a photograph is pure and truthful becomes believable. Barthes argues that the combination (and opposition) of both the non-coded and the coded cultural message, give a photograph its ability to relate to human history. As we have learned earlier in the unit, the idea of a point in history brought forward into the present via a variety of contemporary interpretations is a power that photography has that perhaps painting does not.

Barthes concludes his essay with the topic of the Rhetoric of the Image, linking back to its title. This deals with the interpretation of the symbolic message, influenced by culture. Barthes argues that the linguistic and denoted messages can be analysed as if a language, but the connoted messages are more difficult as they vary from culture to culture and are influence heavily by our attitudes and ideals around the signs in an image. In his analysis of the Panzani advert he identified four connoted signs but argues that there are most likely to be many more that depend on different areas of knowledge. He then goes on to conclude that the symbolic message within the image naturalises or balances the relationship between what is systematic denotation (what each element physically represents) and what is connoted (i.e. the potential meanings shaped by the environmental aspects mentioned previously). The rhetoric being referred to is how an image can be used to persuade the viewer in terms of what the image is about by using the structured meanings of the elements in the frame, but also by playing on their own psychological reactions to them.

Conclusion

Like many, I find Barthes difficult to read primarily because of his use of language and its translation from French to English. That said, there are some key messages from this particular essay in understanding how images can be used to structure meaning to a specific audience and how any use of text being either explanatory or suggestive depending on its relationship with the symbolic messages. Anchorage and Relay are shown to be used singularly, depending on the type of image. Anchorage as we have seen, signposts the viewer to the meaning of the image without leaving any room for interpretation and is used most frequently in journalism. However, I found Barthes’ explanation of Relay interesting because the text offers significant clues to what the image is about while letting the viewer build their own interpretation of the iconic message. Its use in comic strips was for me the revelation as relay hides in plain sight. If we consider a comic, we can understand the plot pretty much from just reading the text in each frame which at first suggests the medium is somehow ‘dumbed down’. The sophistication of comics is revealed in the way the text directs us to really look at the image and it is at this point that we realise that the symbolic messages in comic strips create many layered narratives. I now understand why when a successful comic strip character is represented in another media such as cinema, there is always significant debate over whether the characters and story arcs are faithful to the original ‘text’, perhaps more so than with traditional literature. Each individual reading of the comic will differ because of the social, environmental and cultural influences that Barthes refers to, but the relay text helps tell the story that the writers intended in the beginning.

In terms of how I might use anchors and relays in my future work, I think the main consideration is who am I creating for? Art is the expression of the artist, but I think I need to focus more on who I am trying to reach with my photography. With Assignment 3, I incorporated relay text in my album covers but the intent was only to support my story of the revival of vinyl without much consideration of how people might relate to it. The subsequent feedback suggested that the strength of reaction to the work was driven by the viewer’s own relationship with vinyl. The images were interesting, but I feel on reflection that the impact of the text wasn’t really strong enough to tell my story. I will endeavour to consider the audience more when thinking about including text in the series.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2020, “On Barthes – Tools for Deconstruction”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/10/25/on-barthes-tools-for-deconstruction/

[2] Fletcher R, 2021, “4) Exercise 1 – Looking at Advertisements”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/09/16/4-exercise-1-looking-at-advertisments/

[3] Unknown Artist, 2011, “Speed Bump”, Image Resource, The Cartoonist Group Website, https://www.cartoonistgroup.com/cartoon/Speed+Bump/2011-02-27/57901

[4] Unknown, 2015, “Doing Film History, Albert Einstein Famous Caricature”, Image Resource, Exeter University Blog, https://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/doingfilmhistory/albert-einstein-famous-caricature/

Pingback: 4) Project 2: Memories and Speech | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Something to look forward to!

LikeLike

It’s a tough read, but an interesting subject

>

LikeLike

I am still, very slowly, plodding through Camera Lucida, interesting but not bedtime reading!

LikeLike

Pingback: Assignment Five: Your Inspiration | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: 5) Project 2: Places and Spaces | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog