You have been developing your skills and confidence in critical thinking and analysis throughout all the projects in this unit (and previous units on the degree). The learning outcomes for this unit include showing your abilities to ‘examine… compare and contrast… outline your understanding… and critique. The project 6 exercises and Critical Review assignment support further honing your critical skills.

Take a moment to reflect on your confidence and understanding of what is meant by critical analysis and review. Familiarise yourself with the library resources and guides available to support skills in Critical Thinking. Post a reflective note on your learning log and on the Ethics and Representation Forum about using writing and speaking.

Reflection

Before my studies on this degree course, I spent over 30 years in engineering, with a long period of that time being both a scientific researcher and electronics engineer. One of the key attributes of that profession is the need to not take anything at face value. If a assumption is made, it must always be verified through some form of testing and the acquisition of data to support a conclusion. That has always made sense to me, but until the past couple of units on this course I hadn’t considered the application of this style of thinking to the creative arts. Critical thinking ideas that have been learned here mirror those concepts in engineering, where an assertion or argument is assessed using supporting and contradicting information. The creative world is entirely subjective, and I have learned that in many cases, particularly regarding photography, that subjectivity is categorised or classified as a result of critical thinking that identifies commonality or consistency in a series of works. A good example of this is the coining of the term ‘Documentary’, which is used to describe photography as a medium for capturing and representing an event, cultural trend or some other pattern of life. Photography was used to carry out this kind of work for decades before John Grierson started to use the expression to describe moving picture documentary, resulting is a retrofitting to the earlier work of photographers like Lewis Hine, Alice Hughes and Walker Evans. In learning about photographic genre and codes in the previous unit, I was able to further relate analysis to photographs with established ideas as the basis for a critical review. My essay last year asked the question about when a photograph does not comply with the usual visual codes of a genre, using Mohamed Bourouissa’s series about Paris’ Le Périphique, a ring road that divides regions of Paris with different social issues. I saw the image that I chose as documentary, while there was an assertion that it was landscape. By looking at the claim, investigating the corroborating and conflicting evidence, assessing against the widely-held ideas of the genres, I was able to draw own conclusions about the work. The evidence was more akin to established practice and historical art than the tested, measured data of my previous career, but I could see how the two uses of critical review could be applied in the same logical way.

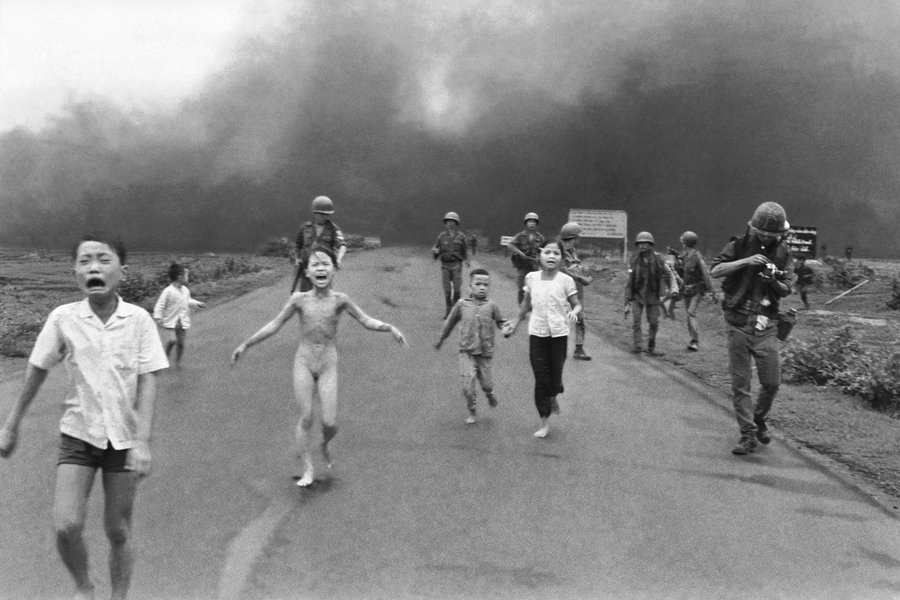

In this unit, we have considered questions that point to whether a photograph should be taken or published from the perspective of whether it is ethical or not, and whether it represents the subject faithfully and respectfully. Key to this learning has been the application of critical analysis to my own practice. By being able to assess the work of other artists and a their ethical standards or otherwise, I’ve been able to ask those same questions of myself. Factored into the thinking is time as context, because those questions are here and now, but often compared with decisions made during a different era. For example, the famous image of Kim Phuc, known as Napalm Girl, could be considered as historically important because anecdotally it helped change the US people’s perspective on the Vietnam war. Ethically, the photographer was doing his job, but the subsequent actions of his editorial in identifying the girl and beginning a spectrum of problems from the shy embarrassment of her nakedness to her use as a propaganda tool, that followed her as she grew up. Contrast this image with Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl (1984), which depicts a young girl staring directly at the photographer. This image was shot by another photojournalist, but it doesn’t specifically depict the horrors of the ongoing Soviet-Afghan war beyond the identification of her as an Afghan refugee. It’s a striking image, but more as a portrait of a girl showing both defiance and vulnerability in her aesthetically beautiful eyes. What happened after the picture was taken echoes the experience of Kim Phuc, although the girl wasn’t made aware of the image’s existence until 28 years after it was taken. In 2019, The Wire reported that the girl, named Sharbat Gula was angry when she was first asked about how she felt about the image (You’ll Never See the Iconic Photo of the ‘Afghan Girl’ the Same Way Again, s.d.). She went on to describe being coerced into showing her face to this total stranger, which for a muslim woman is considered sinful. The article goes on to question how McCurry and the publisher didn’t know or appreciate this at the time. For me, there is a vast difference between documenting a war and manipulating its victims into being photographed.

In terms of representation, we have looked at how to build relationships and earn trust with subjects ranging from complete strangers to vulnerable people, which may not appear at first to form part of critical analysis. However, by learning about our subject’s story in their own words, we are gathering evidence that may support or contradict our initial pre-conceptions. Working collaboratively moves us to a position where we avoid ethical issues such as harm or embarrassment, but also helps us avoid fixating on a single part of their identity. In the case of my planned SDP, achieving a balance between telling a story about the problems faced by LGBTQ+ and representing them as who they are: people who are not defined by their gender identity or sexuality. I recently wrote a post on my personal blog about unconscious bias and the danger it poses to our being able to see the real story.

https://www.richperspective.co.uk/blog/2023/10/check-your-bias-at-the-door

Conclusion

If critical analysis is defined as a lifecycle of description, analysis and evaluation, we have demonstrated its application to both works and behaviours in the context of ethics and representation. The benefits of reasoned argument, comparing and contrasting other practicitioners’ takes on a similar situation and supported by the clear and concise way that the thinking can be communicated. I asked one of my SDP subjects to consider how he wanted to be represented as a man, and as a gay man, before our shoot. When I arrived at his house, it was clear that he had conduced his own critical thinking on my question, because he identified three ways in which he believed people saw him. He asked himself whether he was subconsciously playing three different parts and to what extent these were defined by events in his life. Once he was able to articulate this, we were able to shoot images that represented all three. Critical thinking is a life skill, not limited to photography or engineering, and this unit has helped to reinforce this crucial point.

References

You’ll Never See the Iconic Photo of the ‘Afghan Girl’ the Same Way Again (s.d.) At: https://thewire.in/media/afghan-girl-steve-mccurry-national-geographic (Accessed 17/10/2023).