Introduction

So far in Part 4, we’ve looked at the use of text or the spoken word to tell factual stories about a subject that we can relate to as real. From the examples of remembering a brief conversation (Favrod), the experiences of domestic abuse (Fox) to the simple yet powerful emotions of a child wanting to establish their relationship with an absent father (Boothroyd), they are all narratives about real life. The photographs aren’t in themselves about real life, though. In Boothroyd’s series [1], the images are carefully constructed tableaux that, as we know, need not be about real events. Instead they need to provide the viewer with enough signifieds that help build a narrative that broadly aligns with the artist’s intent. Our imaginations and specific experiences fill in the blanks in the narratives, for example my own experiences of feeling isolated as a teenager and subsequent mental illness related to the death of my mother, made Boothroyd’s series resonate with me in a way that every tableau made sense to me. This is what we have learned about reading photographs; there is an artist intent that revolves around a personal interest, experience or story that they want to tell. What we realise though is that the story doesn’t have to be factual in nature – the photographer has an imagination as well. So what happens when the imagery and text are freed from being firmly anchored in reality?

Michael Colvin – Rubber Flapper (2015)

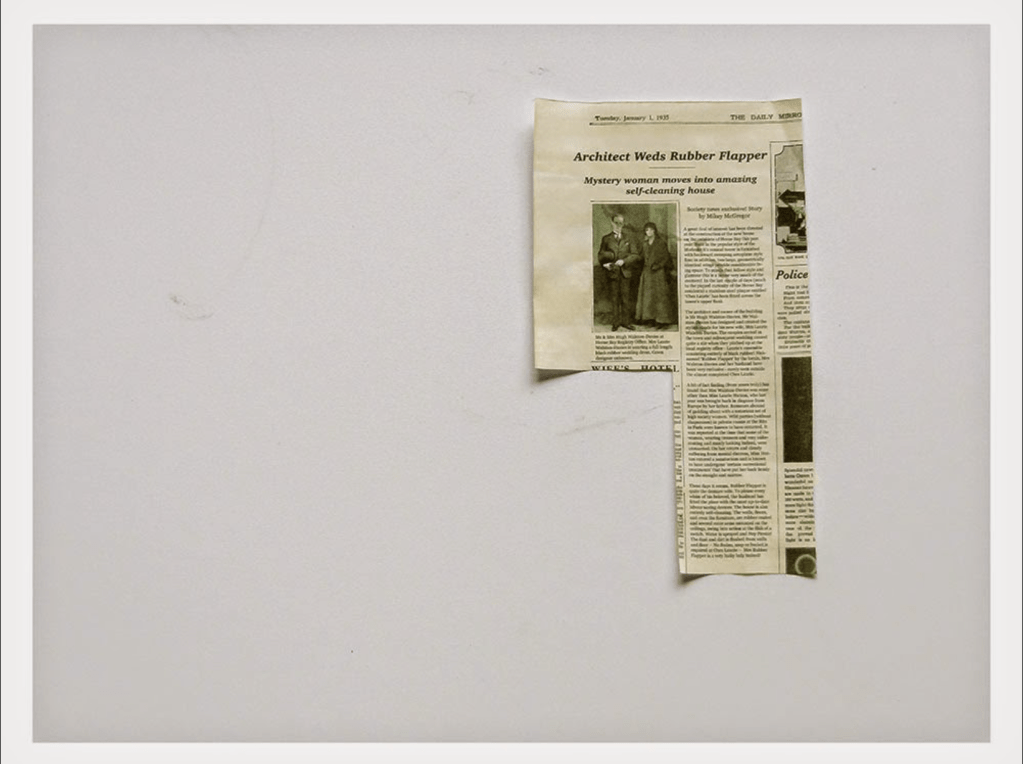

This narrative series by Colvin is the subject of an interview that he gave with OCA, where he describes how his ideas for narratives came about. The basis for the series comes from the refusal of Staten Island Officials in New York to acknowledge the sexuality and relationship of 19th Century photographer Alice Austen. Austen and Gertrude Tate lived together as ‘companions’ and partners in the tea room they ran in Clear Comfort, NY. The extent of their relationship was both hidden from and denied by the women’s families to the extent that their final wishes to be buried together was ignored. Colvin related to the denial of gay sexuality and used the further historical control of Austen’s estate, principally the refusal to allow research of her archive of work at the time of his assignment, to create a fictional documentary of a secretive woman who lived in a self-cleaning house. The narrative that the series creates a sense of observing the bizarre, sympathetically trying to uncover the ‘truth’ of the character’s life and a sense of unwanted intrusion when he makes progress with this quest. We have a combination of words and text that make the character come to life as Colvin places himself in the role of investigator. Colvin’s use of text is interesting here because he combines a related event with complete works of fiction. In the example below, we see what looks like a real newspaper cutting about an mysterious woman and her new husband living in a self-cleaning house. It’s based on Colvin’s discovery that someone did build such a house and lived in it for many years, but the cutting is a prop created by the artist. He includes it as a sort of scrapbook image with a more readable transcript telling some of the Flapper’s story to the viewer.

Another textual element comes in the form of a letter from the legal representative in charge of the character’s estate who withdraw’s consent to use material from her archive when the artist uncovers her sexuality. This connection to Austen, while fictional, tells a story about cultural attitudes towards lesbianism both historically and in the contemporary sense. Colvin’s series is shot to look archival and is so convincing that it’s difficult to tell real from imaginary. I find Colvin’s attention to detail astonishing, from the carefully constructed props to the post-processing and collage work that create the scrapbook aesthetic. What the combination of constructed text achieves here is the storytelling pointers that provide the context needed to interpret the series. By making the text the actual image as in the above, the series is completely plausible. Without the inclusion of these self-contained iconic messages, the series remains fantastical but lacks the glue to holds the narrative together.

Christian Patterson – Redheaded Peckerwood (2011)

With Patterson’s series, the key difference is that while Colvin was creating a fictional story that had some element of believable ‘truth’ to it, Redheaded Peckerwood is based on an actual event. The killing spree of two Wyoming teenagers in the 1950s was a notorious enough story to the extent that it had been used as the inspiration for a film called Badlands. In an interview with Jörg Colberg[3], Patterson said that he was surprised at how the real story of the murders was stranger and more tragic than the fictional portrayal in the film and he went on to think about how to tell that story through his own imagery. Patterson followed the route taken by the killers, investigated a variety of aspects of the case and used a mixture of real imagery (forensic photographs, news reports) alongside his own recreated tableaux photographs. He mixed composition style, colour vs. black and white and in some cased fabricated an image in terms of its place in the timeline, all to tell the story from his perspective and point of interest.

“I often say that Redheaded Peckerwood is a body of photographs, documents and objects that utilizes a true crime story as a spine. The story continually served as a source of inspiration and ideas, but what really excited me about my work was the expansion of my own artistic practice”

Christian Patterson[3]

Perhaps the most unusual images in the series are the constructed pseudo-quotations like the one below:

The phrase “you don’t know shit from Shinola” has been part of the US lexicon for many years, even after Shinola, a well known brand of shoe polish, went out of production. It’s a term that means ‘ignorant’ through the suggestion that someone cannot tell one thing from another. The image itself shows the product spilling over a surface and revealing a texture which isn’t obvious. Perhaps its addition in the series suggests that all is not what it seems in the story of the two killers. Aesthetically the image could be straight out of a 1950s advertisement, which matches most of the photography in the rest of the series. This is what the series has in common with Colvin’s. The fantastical meanings are there to be seen, but the photography and use of fiction makes us question the almost-default idea of the medium being truthful of documentary. We don’t know what is real and what is imaginary in either case, but both tell a couples story.

“Ultimately, I wanted the work to act as a more complex, enigmatic visual crime dossier — a mixed collection of cryptic clues, random facts and fictions that the viewer had to deal with on their own, to some extent.”

Christian Patterson[3]

Joan Fontcuberta – Stranger Than Fiction

The last of the artist mentioned in this Project is Joan Fontcuberta who takes the confusion with what is real and what isn’t to a whole other level. His series Stranger Than Fiction shows us fantastical ‘evidence’ of creatures, plants, people etc. that are so outragrous as to lead us to question what we know. When I first saw them I was reminded of the spoof journalism of the tabloids with their photographic proof of things like ‘a double decker bus found on the moon’ that were so ridiculous that they couldn’t possibly be real. Such lunacy doesn’t bring our faith in journalism or photography evidence of the truth into question, but there is something about Fontcuberta’s work that makes us wonder. Take the example below from the sub-narrative set called Sirens.

This photograph depicts the remains of a mythical creature call the Hydropitecus which clearly has the tail of a fish and humanoid skeleton, making it a siren or mermaid. The creature is fossilised in rock, lending credence to its age. We are told by the story that accompanies the series that the creature was discovered by a priest called Jean Fontana and is detailed in published scientific journals. The whole thing looks convincing enough that we need to apply our knowledge of history, folklore and mythology to review the narrative, after which we realise that it is totally fake. Then we notice the similarities between the artist’s name and the priest in the story, which sets our minds at ease – we were not fooled after all. The rest of Fontcuberta’s work in the series messes with what we believe to be true, with millipedes sporting full limbs, monkeys with turtle heads etc an in each case some legitimacy added by text or supporting documents.

“The idea that photography lies is based on a complete misunderstanding of what photography actually is or does. Photographs, by themselves, don’t do anything. They’re just photographs. But they can be made to tell a story or tall tale or outright lie when they are being placed in context, when they’re used to tell a story that might or might not be true”.

Jörg Colberg discussing the work of Joan Fontcuberta[6]

Open vs. Closed Narratives

The final part of this section of the course notes deals with the difference between open and closed narratives. Open narratives are those where the viewer or reader is invited to bring their own interpretation to the work through the text that is included in some way. The artists we have covered in Part 4 use primarily open narratives because it gives the work more depth; the text acts as relay in guiding them to a conclusion about what the work means. When we incorporate text that informs more than invites, i.e. anchors the story, we leave little room for the viewer to create their own. Examples of literature and cinema could be considered more closed than open. The notes highlight the importance of the difference between closed narratives and ‘closure’, the latter being inviting the viewer to draw their own conclusion from the many narrative paths to achieve some understanding. Closure does not mean that the narrative lacks the space for the viewer to bring their own ideas, more that it helps with the decision being made. The notes conclude with ways of thinking about narratives and how to use both fiction and non-fiction to enhance the visuals in our artwork.

Conclusion

The main learning from this project is that we as artists have the flexibility to completely fabricate our own truths with our work. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, but it does. The truth of photography as a medium is that people still see it as a factual representation that must real in some way. The artists here have used photography as a tool to challenge both our understanding of the medium but also so tell a story a particular way. Colvin explores the politics of sexuality and the denial or shame that society still struggles with when being honest about how they feel. We find ourselves wanting to know more about his character while all the time being taken in by the apparent authenticity of the documentary. Patterson combines the real story with his own research and perspective on the horrific crimes. The series mixes aesthetics but still manages to leave us confused about what is historical fact and the views of a contemporary artist. Finally, Fontcuberto messes with our belief system by making us look closely at the often jarringly obvious fabrications, as if asking “can you be sure, though?”. One consistency though is the impact of words in the form of text, supporting notes or as visuals themselves. Without the words, each artwork remains interesting but will little cohesion. Whether or not we choose to be inspired to be real or imaginary is really down to personal choice.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2021, 4) Project 2: Memories and Speech”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/11/05/4-project-2-memories-and-speech/

[2] Colvin M, 2015, “Assignment 2 – Rubber Flapper”, A Partial Moment Blog, http://apartialmoment.blogspot.com/2015/01/assignment-2-rubber-flapper.html

[3] Colberg J, 2012, “A Conversation with Christan Patterson”, Conscientious Extended Magazine, http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/extended/archives/a_conversation_with_christian_patterson/

[4] Patterson C, Unknown Date, “Redheaded Peckerwood – Photographs and Text by Christian Patterson, Image Resource, LensCulture, https://www.lensculture.com/articles/christian-patterson-redheaded-peckerwood#slideshow

[5] Science and Media Museum, 2015, “Joan Fontcuberta: Stranger Than Fiction”, Image Resource, Exhibition Website, https://www.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/what-was-on/joan-fontcuberta-stranger-fiction

[6] Colberg J, 2014, “The Photography of Nature and The Nature of Photography”, Conscientious Photography Magazine, https://www.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/what-was-on/joan-fontcuberta-stranger-fiction

Interesting Richard but I do find myself asking the question, particularly about Fontcuberto’s work ‘Why?’ But perhaps I am missing something.

LikeLike

Pingback: Reflecting on Identity and Place | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog