Introduction

This project deals with the idea of an artist’s work being a mirror for their experience or their influence over the narratives within the image or series.

Mary Kelly: Post-Partum Document (1973 to 79)

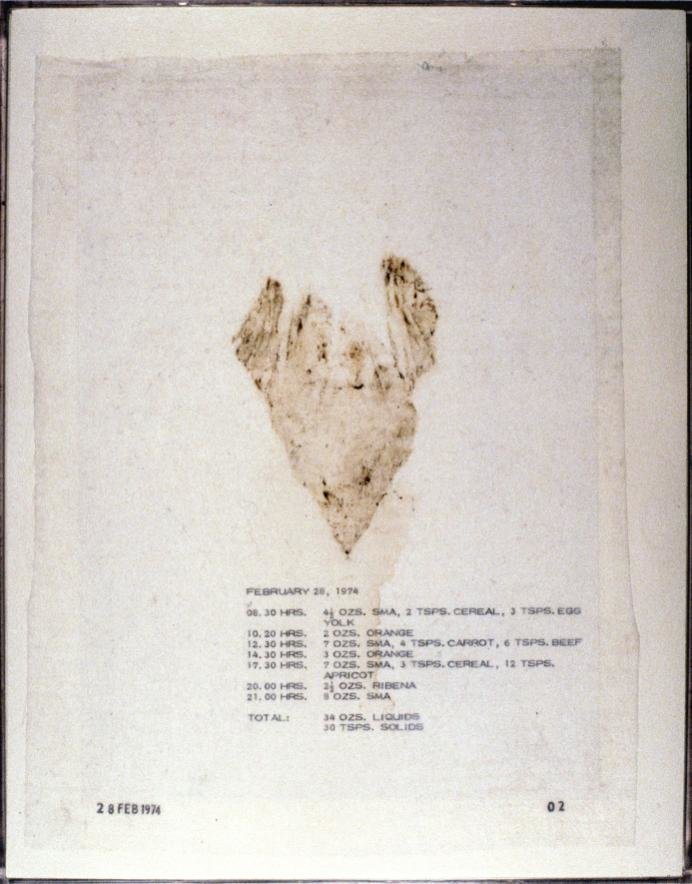

We are first introduced to American artist Mary Kelly, who created a documentary of the first 5 years of her son’s life in the early seventies. Kelly’s work is not photographic, instead using a variety of everyday items and transcripts of specific events to tell the story of early motherhood. Kelly’s intent for the work was to challenge the established idea of the ‘division of labour’ between the genders and she did this by representing a new mother dealing with the daily domestic activities with a young child. As Kelly was ‘post-partum’ herself, her work is told as a mirror of her own experiences. In an interview [1], Kelly said that she wanted the viewer to concentrate on the subject rather than focusing on the fact that a woman was telling it, so to me it was as much about getting the story told than it being about the artist. However, Kelly’s approach to the documentary is her own perspective on the day to day aspects of raising a child. Her work is almost scientific in approach, with meticulous notes and items included; the most infamous artefacts being her collection of nappy stains.

Kelly used them alongside a diary entry for the food that her baby had consumed that particular day. Her view was that the best way to see the baby’s development was to measure the output for a given input. This reminds me not only of a scientific approach to a problem, but also the work of Gideon Mendel. His documentary series Dzhangal[3] arranges the possessions left behind by migrants when they left the holding camp at Calais. I looked at this work as part of Context and Narrative, but it is now that I understand Mendel’s work as a mirror. His parents were Jewish refugees who escaped the Holocaust, which Mendel used to tell the stories of the disposed from his own personal perspective. The items themselves were randomly discarded, but the artist’s arrangement of them in the work juxstaposes the mundane with the signs of the oppressive treatment the migrants suffered as they were held at the camp. Both Mendel and Kelly avoid the obvious in their representations but their experiences come through clearly in the work.

Research Task: Elina Brotherus – this article can be seen at: https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/08/02/research-task-elina-brotherus/

Esther Teichmann (1980 -)

In a similar way to both Kelly and Brotherus, Esther Teichmann mixes a number of media to create her work. Her work first interested me because it is almost collage in nature, with the underlying photographic element being only one part of the creative process. If I reflect on my work on this course thus far, it’s easy to see how the act of photographing in the portrait genre limits my creativity. While I do think about what I’m trying to represent in the subject, the context, composition and lighting are prioritised to make an image. Teichmann, like the other artists, is exploring the relationships between subjects from her perspective and using whatever media helps her express herself.

Photography is always at the centre of my practice and was definitely my starting point. I think it’s such an elastic and physical medium, but fundamentally the thing that draws me in is the relationship between the real and the staged, the duality between the real and the constructed, the world that exists and the otherworldly. It’s this dynamic that keeps me wedded to the medium and continually excited by it.

Esther Teichmann in conversation with Emily Spicer of Studio International Magazine, 2020 [4]

The quote above makes the point that there is no reason for photography to remain in the real or documentary world. but instead can create a sense of the unbelievable. This makes perfect sense, of course but the learning for me is going to be how to embrace this as an idea in my own work.

Tecihmann’s work is clearly very personal and often evokes raw memories of her earlier life, of mourning and loss both as something that is experienced or anticipated. She makes an interesting point in the interview[4] about loss being both past and future where as a child we develop an understanding that we will inevitably lose something or someone and as we grow, we experience it. These experiences are inextricably linked but are also very different and are naturally unique to the sufferer. For me, this acknowledgement reveals why Teichmann’s work is so relatable despite her experiences being very different from mine. Her work is more impactful to me than Kelly’s because I have no relatable experiences in the case of the latter. Brotherus’ work creates a sense of empathy and recognisable heartache, but again I have little in terms of reference. Teichmann’s work, particularly Mythologies (2012 to 2014) evokes a sense of the sadness of isolation in what on the surface appears to be a bright, colourful and unnatural world.

When we look closer, the beauty of the surroundings takes on a sinister feel with it’s unreal colouring and enclosed nature. Teichmann’s hand-colouring of the images is fairly obvious, but for me that introduces the mirror of her experiences into the image.

The course notes make a point about how we might approach a mirror work based on our own lives

“Using mirrors of the self does not have to result in highly personal, therapeutic work, although it might. Think carefully about the issues you want to avoid and what you’re willing to make public should you decide to take this route. There are sophisticated ways of portraying situations that don’t entail divulging everything”

Identity and Place course notes Part 3, page 6

This is an interesting point in terms of choosing what part of ourselves to put into our photographs. It could simply range from an opinion on a topic based on experience, as with diCorcia’s series Hustlers, to something much more personal. Although not a direct reference, diCorcia was inspired to shoot the series of portraits of male prostitutes following the death of his brother from AIDS. His pictures have many possible interpretations, but diCorcia’s experience of loss comes through in the sympathetic way he represents the subjects. In this case, the artist isn’t really revealing himself in the images, rather including his sadness and bewilderment at the struggles of gay men in sex industry during the AIDS epidemic. In representing them this way, he is remains safely detached from the subject. In my case, the recent feedback on Assignment 2 about my self-censorship leads me to consider my subject for Assignment 3 carefully. My ideas centre around my own struggles with recovering from depression which have included a spell in hospital, excessive drinking, inability to work etc. While I am not ashamed or embarrassed by it, I wonder if my internal censorship prevents me from being completely honest about it in my work. This is something I will have to decide upon as I start working on the assignment.

Hans Eijkelboom – With my Family (1973)

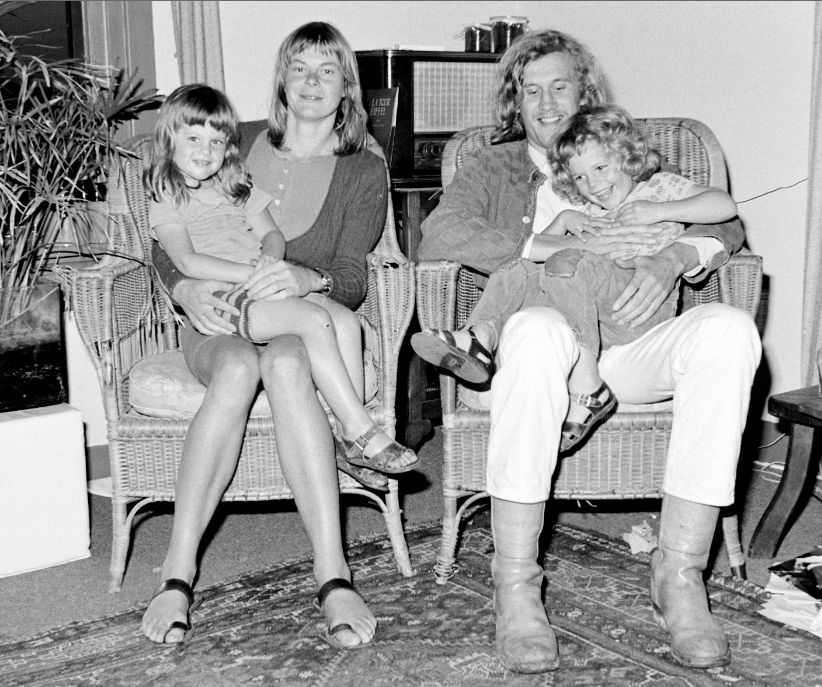

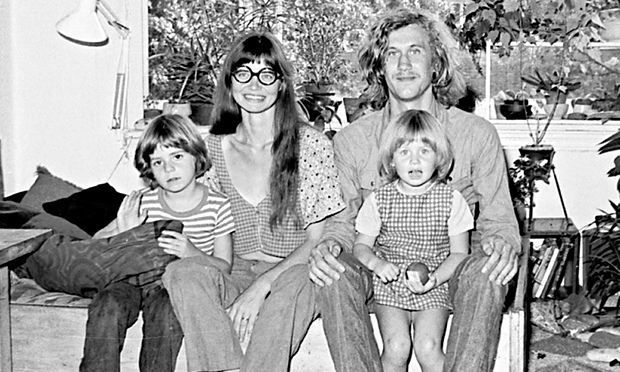

When I first saw this work, I was immediately reminded of Trish Morrissey’s Front (2005 – 2007) as the idea is similar. Eijkelboom pre-dates her work by 42 years but the similarities go further than the aesthetic. Eijkelboom waited for the men of the house to leave for work and knocked on the door [6], which seems like something we just wouldn’t do these days. Like Morrissey, he persuaded the mothers and their children to pose with him in what appears to be a completely natural scene. When viewed individually, there is nothing to reveal the deception but when the series is shown together, the viewer immediately asks how one man could have so many families. As well as the humorous aspects, the series is a commentary on the traditional ‘nuclear family’ with Eijkelboom at the centre of it.

From the series With My Family (1973) by ns Eijkelboom [7]

From the series With My Family (1973) by ns Eijkelboom [7]

Eijkelboom shows us a blurring of artist and subject in the way the others in the frame interact with him to the extent that we are drawn to the dynamics of the fabricated families in an entirely relatable way. When Morrissey approached her subjects on the beach for Front, she went one step further. She asked to swap clothes with one of the women in the group as a way of replacing them in the scene. What we see when we look at that work is something clever but also subversive; Morrissey does nothing to blend in with her surroundings as Eijkelboom did. In addition, some of her compositions deliberately contrast her with her surroundings as in the example below.

When we look at this image, the obvious thought is around whether Morrissey could be the mother of the child. Depending on how much or how little the viewer understands about racial genetics will determine how this photograph is interpreted. For me, the overwhelming message in the picture is the challenge to a ‘rush of judgement’ which is effectively provoked by the artist holding up a mirror to our view of the traditional concept of family. Like Eijkelboom, she succeeds in putting herself in the narrative I get a different sense of the mirror between the two artists; the former being a chameleon and the latter a cuckoo.

Hans Eijkelboom – Identities (1970 to 2017)

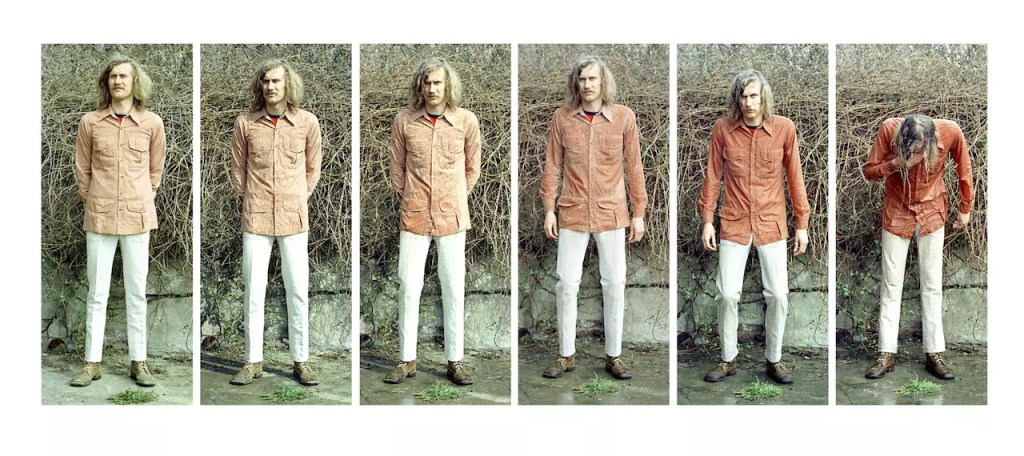

With Identities (1970 to 2017), the first thing that is apparent is that Eijkelboom has been exploring the ideas of what constitutes identity for many years. Not limiting himself to the basic constructs of age, race and gender, instead we have a series that looks at the more subtle elements such as interests, fashion, physical stature etc. Some of the photographs are of the artist himself, dressed in the same clothing from frame to frame but reacting to something that is happening around him. In the example below, a young Eijkelboom is seen standing in what we assume to be a rainstorm. Arranged linearly, the sequence shows him reacting to getting wetter as the rain intensifies. The clothing and the poses are largely the same with the exception of the final frame where he succumbs to the storm.

My interpretation of this image is of a man who is defined, at least in the first instance, by his clothes and general appearance. As the environment around him changes, these identifying features subtly change with them, yet they remain familiar throughout. Our perspective is drawn to the repetition but also the way his personality responds to standing in the rain. There is a sense of humour with this image that we see elsewhere in this vast collection.

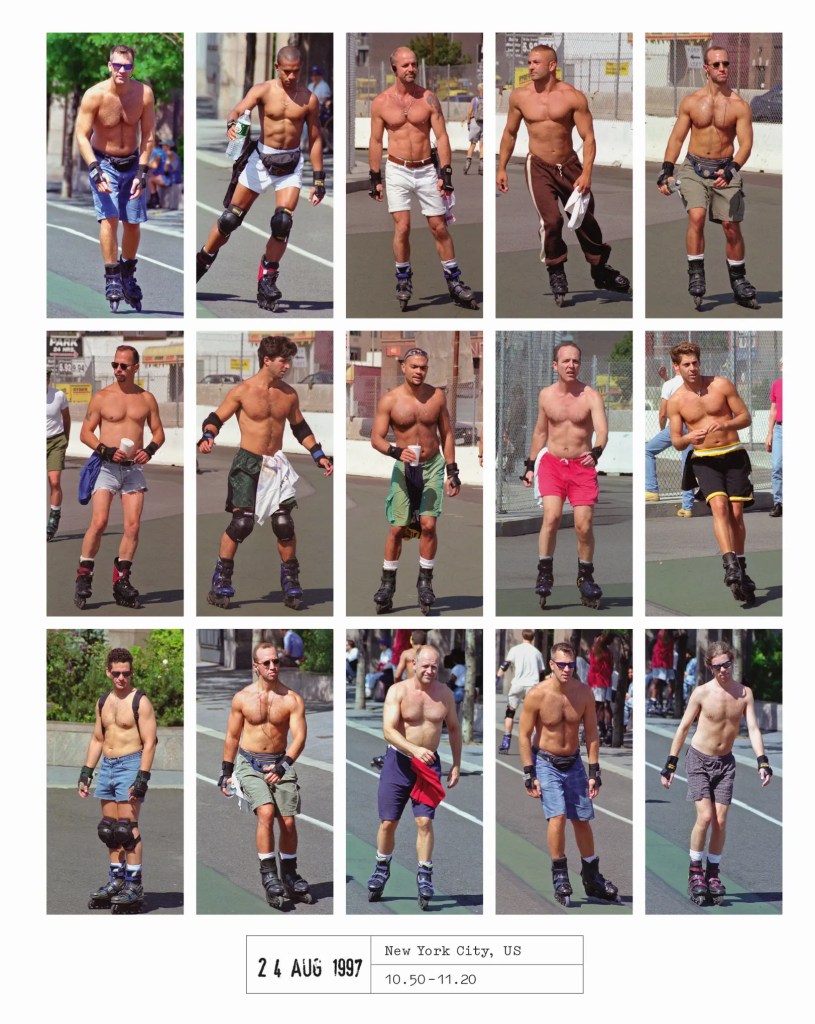

Another element that features heavily in his work is typology, which we covered in Part 1. Eijkelboom collects street typologies through shooting people who are unaware of his presence. In an interview with Phaidon about a later project ‘People of the Twenty First Century’, Eijkelboom describes his working with a camera around his neck, operating by a hidden trigger in a similar way to Evans [9] which resulted in a series of completely natural photographs of people in the street. In the example below, we see the relationship to the Bechers in his use of typology.

Here we have a grid of photographs presented as a single document that forms part of the wider series. The typology is men rollerblading in the sunshine, which in a similar way to the Bechers’ water towers is a representation many subjects in almost identical situations. The key differences are what identifies each subject. They are all dressed differently, have different physiques, are facing and looking in different directions etc, which is what we are drawn to above the ‘normalised’ composition. Here Eijkelboom is showing us the commonality between people and their lives (in this case a leisure activity), while maintaining their own identity while doing it. Similar work in this series ‘collects’ people wearing the same clothing brand, style or colour which contrasts with the other photographs where Eijkelboom is the main subject.

Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin

We are reintroduced to Sherman and Goldin as examples fo artists using the mirror as a way of presenting their perspective on a subject. Sherman’s Centrefolds (1981) challenges the impact of the sexualisation and often related victimisation of women through the aesthetic of print media. Her self-portraits photographs show the sinister side of what at first glance could pass as glossy glamour, the poses and haunting expressions being Sherman’s way of pointing out that this is not ok. Sherman wasn’t necessarily saying something about herself with this series, but expressing her opinion as a woman clearly horrified by the apparent acceptability of female exploitation. Goldin by contrast was an ‘insider’ in a part of New York society that was considered fringe by the majority of the population. The notes talk about Goldin challenging social acceptance of her and her friends, but as Goldin herself said

‘My work has always come from empathy and love’

Nan Goldin (2014) [11]

I would question whether Goldin was challenging the idea of acceptance, rather she was acutely aware of the difficulties in the lives of her friends and wanted to represent how important they were to her. Whatever her motives, Goldin uses the ‘mirror’ as an insider to the experience in way that makes us feel like we know her life through her work.

Conclusion

My main conclusion from this project has been the understanding that the mirror can be very personal to the photographer through their own experiences, but also can be a commentary on their perspective on a situation. We learned in a previous course that portraiture can be anything from a straight representation of the subject to not being about them at all. We can use other people to act out our life experiences as portraiture as well as not having a human subject in the frame at all. However in this unit, the concept is more of identity than portraiture. How do we say something about a subject whether physical or spiritual through photography? In the case of Kelly, she narrates the experience of women in the role of mother and carer through the use of very factual documentary using her own artefacts and experiences. She achieves a strong identity without having any portraiture as part of the series. In the case of Eijkelboom, he places himself in the roles of others to reveal something about their lives as well as collecting the many attributes of someone’s identity as seen by a casual observer, such as clothing, interests etc. The common theme through his work is his sense of humour, which I think is what makes the series a mirror of his personality. With Sherman there is strong storytelling with the artist playing a variety of parts. She is mirroring her views on the exploitation of women but not necessarily from a clear, personal experience. With Goldin, the work creates narratives from an insider perspective which gives it a greater authenticity than perhaps Sherman’s Centrefolds does. The Goldin work emphasises the personal nature of working in ‘mirror’ as there is little of her life that remains private.

References

[1] Eirkssen U, 2010, “Four Works in Dialogue”, The British Library, http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/sisterhood/clips/culture-and-the-arts/visual-arts/143927.html

[2] McCloskey P, 2013, “Post-Partum Document and Effect”, Image Resource, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Mary-Kelly-Post-Partum-Document-Documentation-I-Analysed-Fecal-Stains-and-Feeding_fig2_285123133

[3] Evening Standard, 2017, “Calais Jungle artist Gideon Mendel: ‘Nigel Farage would despise this exhibition'”, Youtube Video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SVrn0XqfnBs

[4] Spicer E, 2020, “Esther Teichmann: ‘My work explores our relationship to the maternal, thinking about the mother as first lover’”, Interview, Studio International, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/esther-teichmann-interview-my-work-explores-our-relationship-to-the-maternal-the-mother-as-first-lover

[5] Teichmann E, 2020, “Mythologies (2012-2014)”, Image Resource, Aritist Website, http://www.estherteichmann.com/pdf/Foam_32_Esther_Teichmann.pdf

[6] O’Hagan S, 2014, “Arles 2014: Hans Eijkelboom and the urbearable Dutchness of being”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jul/11/arles-2014-hans-eijkelboom-dutch-group-show

[7] Jackson A, 2017, “Hans Eijkelboom gets a major retrospective in The Hague”, The British Journal of Photography, https://www.1854.photography/2017/09/hans-eijkelboom-retrospective/

[8 Morrissey T, 2021, “Trish Morrissey”,Image Resource, Lens Culture, https://www.lensculture.com/trish-morrissey?modal=project-229261

[9] Diaconov V, Date Unknown, “Hans Eijkelboom: “Fewer and fewer people are part of a group”, Interview with Garage Magazine, https://garagemca.org/en/exhibition/i-the-fabric-of-felicity-2018-i/materials/hans-eykelbom-lyudi-vse-rezhe-otnosyat-sebya-k-subkulturam-hans-eijkelboom-fewer-and-fewer-people-are-part-of-a-group

[10] Petridis A, 2014, “Snap! the clothing clans of the 21st Century – In Pictures, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2014/oct/23/hans-eijkelboom-people-of-21st-century-photography#img-2

[11] Tate, 2014, “Nan Goldin – My Work Comes from Empathy and Love, Tateshots, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_rVyt-ojpY

Thank you for sharing!

LikeLike

Pingback: Assignment Three: Mirrors or Windows | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: Reflecting on Identity and Place | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog