Complete these two tasks:

- Listen to this interview with Chrystal Ding on The Photo Ethics Podcast as she talks about discomfort as a means through which to learn and grow.

- Read The Politics of Representation Collective’s (2019) interview with Savannah Dodd on Medium [online].

How do you currently understand photography ethics? Reflecting on Chrystal’s quote about ‘digging into your discomfort’, can you identify any areas in your experience as a photographer where you felt unsure or unclear about what you were doing in your photographic role? How might you revisit that time now, what might you do differently? Post your thoughts to your learning log. You might also like to share your reflection on the Ethics and Representation Forum.

My Understanding of Photography Ethics

Cambridge Dictionary definition of Ethics:

“the study of what is morally right and what is not:”

(ethics, 2023)[1]

Simply put, ethics is a determination of whether something is appropriate to a level of moral standard, or contravenes that standard in some way. As human beings, our standards of morality vary between people, are shaped by culture and experience, and define an internal barometer for our behaviour. When applied to photography and photographers, the ethical considerations apply to the decision to make work that represents people or events that impact their lives. How a subject is represented is a hugely complex space, which covers everything from ethnicity and sexuality, to behaviour and personal circumstance. In the interview with Chrystal Ding[2], I recognised the discomfort that she talks about in some of my own work where I’ve photographed people in a certain context. The first example was a trip that I went on in 2015 to Morocco. I’d already been told how its people didn’t like to be photographed, because in the Muslim religion, the creation of a person’s image is said to be taking part of their soul. At the time, my view was that it was an organised photographic trip, so that in some way entitled me to take photographs while on excursion. Like any tourist, I was 100% observer, having no experience, connection or relationship with my potential subjects. What happened was that we, as a group, encountered a great deal of hostility because we were photographing when consent was clearly not given. I recall the first evening’s call to prayer in Marrakesh, when an elderly man got his mat out in the street, knelt on it, then looked up at me with extreme anger in his eyes. I had my camera around my neck, but was not holding it in a way that suggested I was about to photograph him. He gave me the middle finger and shouted to me to “fuck off”, which was possibly the only English words he knew. Clearly, his assumption was that I would not respect his sacred moment of prayer, perhaps driven by the behaviour of other tourists in the city, and that his gesture would somehow put me off taking a picture of him. The irony is that the middle finger would have produced an image that reflected the mood perfectly. If I had shot and disseminated such a photograph, I would have further conveyed the stereotype that the people of Morocco don’t like tourists, particularly photographers. In actual fact, there were a few instances where a brief conversation with the subject, and a monetary transaction, secured an image. What I take from this now, with the benefit of Ding’s interview, was my lack of preparation or research into how to represent my trip in a culturally respectful manner. Even though I’d acted appropriately at the time, it was likely driven by fear for my safety than the moral judgement that it wasn’t appropriate to photograph him. I would not repeat this experience as I didn’t really connect with the country or the city. However if presented with photographing the people of another country, I would certainly carry out more research into its people, how they want to be viewed (if at all) and which part of their culture or daily lives I would want to represent. Only then could I make the decisions need in preparation for shooting the work.

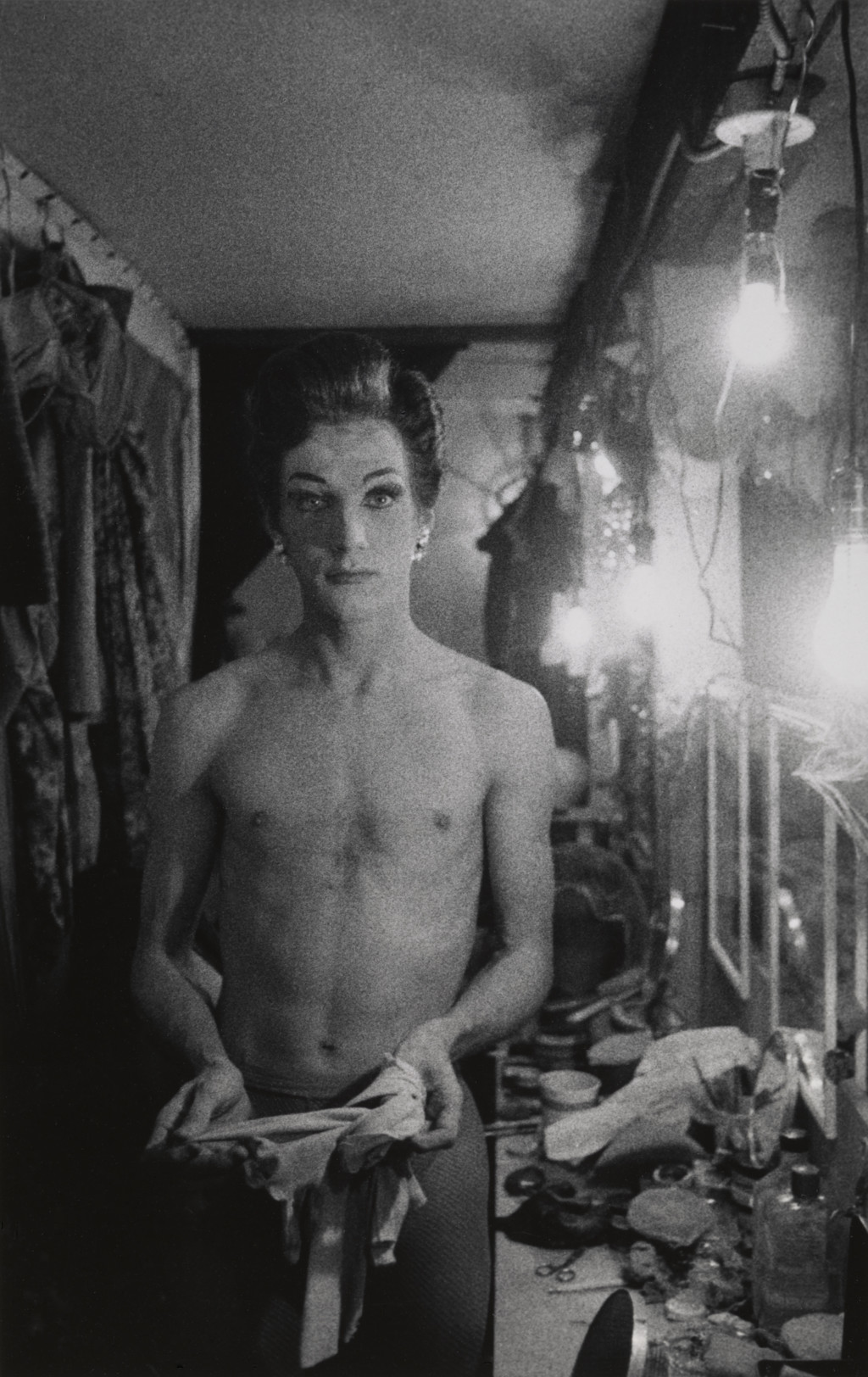

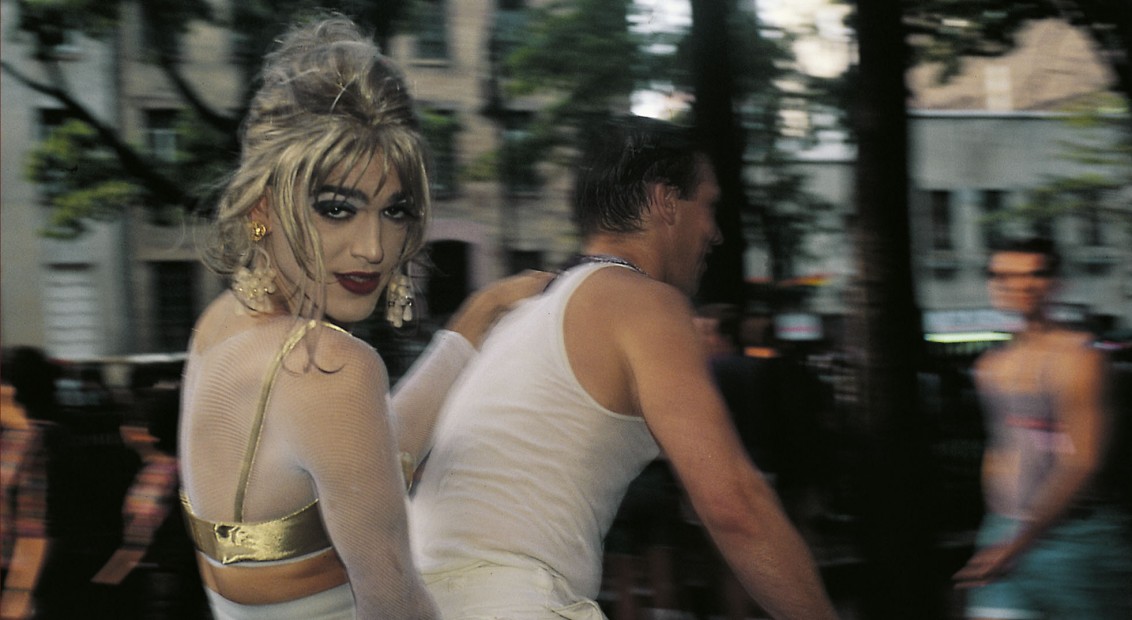

The second example plays more to Ding’s comments about observer vs. participant, which is also highlighted in the interview with Savannah Dodd [3]. Last year, I was engaged to photograph the Malvern Pride event by a friend of mine who was on the committee. I was happy to volunteer to do this as I had wanted to engage with more local civic activities after living in Malvern for over 20 years. The brief was simple: to document the day in its entirety. Although apparently simple, there were many aspects I needed to consider before shooting. Firstly the idea of approaching people to ask for a picture (consent) and to capture the ‘unaware’ documentary images of the event itself. Most of the people I talked to on the day were happy to be photographed but some were not. Our conversations were generally around whether or not they were having a good time, whether they enjoyed the acts etc. However, on a couple of occasions, I was confronted with “oh, I’m not gay…why would you want to photograph me?” At the time, I diffused their discomfort by point out that I wasn’t gay either, but on reflection I believe their discomfort was related to somehow being fraudulently represented in an event that they were simply attending because it was in a public park. My pithy reaction was a way of assuaging my own discomfort at being a straight man photographing an LGBT event. Aside from this, the other ethical concern that I now have when reflecting on the event was “am I representing the event appropriately?” I had been told by the organisers that this was a party, a celebration of the LGBT community that was new for our little Victorian town. However, the local council had rejected the committee’s request for a march through the town, which is actually the core purpose of pride. The marches show the world that the community is proud of who they are and is, by definition, a protest against prejudice and discrimination aimed at their community. Without the marching, the mood of the event was indeed a party, but my responsibility as a photographer should have been to represent the whole purpose of the event, rather than the convenient part, which positively demonstrated the LGBT community as being inclusive in the context of the Malvern residents. There was one image from the event that I feel represented the protest context of Pride, shown below:

In this image, a speaker is reading out her protest poetry about the treatment of young trans people by the elements of society that don’t recognise their gender. This image is the only one in the series of 90 images where the subject isn’t smiling or enjoying themselves. I took the picture because I suddenly became aware of the need to photograph the counter-aesthetic, but on reflection I should have made that part of my practice on the day.

Conclusion

In conclusion, what photographic ethics means to me is the application of a continually evolving set of questions about the subject and my relationship with it. Do I have the right in some related context, to photograph this situation, and if I do then how does that affect my judgement in representing it? The strength of that relationship defines how uncomfortable I am in taking photographs. Rather than finding a connection that justifies the work, I have a need to establish it before that discomfort abates. I agree with Chrystal Ding’s comments about digging into what makes us uncomfortable as this is the sub-conscious ethical standards we all have that are speaking to us. I’m not sure that I would go to the lengths of prior research that she does before photographing, though. This may be because I recognise an impatience in myself that would prevent me from focusing on a single objective for that long without some form of visual experimentation taking place. However, she and Savannah both make the point that considering ethics is a dynamic activity that evolves with our continued development as photographers. The point that we will always have gaps in our knowledge or research, that we will still make decisions we may eventually regret, and should embrace them, really resonated with me.

References

[1] ethics (2023) At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/ethics (Accessed 17/03/2023).

[2] Chrystal Ding: On learning through discomfort (2021) At: https://www.photoethics.org/podcast/chrystal-ding (Accessed 18/03/2023).

[3] Collective, T. P. of R. (2019) Interview with Savannah Dodd, Photography Ethics Centre. At: https://medium.com/the-politics-of-representation/interview-with-savannah-dodd-photography-ethics-centre-ca173c5a9f83 (Accessed 18/03/2023).