The Brief

What ethical principles guide your work as a photographer?

Do some independent research and self-reflection to generate a list of ethical principles that are important to you in your work as a photographer.

Define each principle in relation to how it relates to your practice. You might want to include some examples to illustrate the principle. Complete this exercise in your learning log, we recommend you define 4-6 principles that feel authentic to your work. Reference where you drew any of the guidelines from.

Response

Research led me to consider the concepts laid out by the National Association of Press Photographers and the Photography Ethics Center, when applied to a number of practitioners, some whose work I admire and others that I do not. The research for this exercise can be seen here:

https://oca.padlet.org/richard5198861/research-for-project-1-exercise-2-fbzq4v0a2ov52rog

In considering my own ethics, I conclude that these are my ethical principles:

Respect as much of the facts as possible

This first principle is a tricky one to define, because the concept of fact and truth are themselves complex. What I mean here is that whatever the situation or story, I see to understand as much of it objectively before deciding on how to represent it. An example would be my experience in Marrakech [1], where I knew so little about the culture, I could only offer my perspective as a tourist.

Avoiding causing direct harm or distress

In looking at Bruce Gilden and his attitude towards his subjects, I realise that I’m not a street photographer. He and Cohen (the other photographer in the Padlet) place themselves directly in confrontation with their subjects. While it’s legal to photograph people in public places in the US and UK, the way that some photographers obstruct their subjects makes me uncomfortable. In Cohen’s case, there is occasional collaboration between subject and photographer, but Gilden appears much more aggressive. All of the street work I’ve done in the past has been from a distance, using a mid-zoom lens. I think it’s that discomfort that makes me work in this way.

Be interested in the wider context

Listening to Sally Mann talk about her projects that involve her family, it’s clear that any doubts she has are eased by considering the wider implications of her work. In particular, photographing her husband, who is very ill, she relies on his bravery in telling his story to counteract the pain of photographing her loved one.

Be open and honest

I think my biggest learning to date in this regard, came from Identity and Place, where we had to photograph people we hadn’t met before [2]. When I started the assignment, I was looking for some kind of segue way into a conversation to convince them to let me shoot them. What actually happened is that I simply talked to them about the course, my objective, where the pictures would be shared and what I would be using them for. This was a much better strategy in terms of building trust between photographer and subject and resulted in pictures I was happy with. I still see most of my subjects from time to time and we still chat, even though the pictures were taken nearly 2 years ago. Honesty helps people understand what their image or representation is going to be used for and offers them a way of challenging or rejecting anything that conflicts with their own values.

Collaborate

The idea of collaborating for me covers many things, including an amalgamation of ideas, representation that is respectful or challenging in a given context, and consent. The Photography Ethics Center uses the example of photographing children as a case for collaboration. A child isn’t developed enough to be able to understand how they are being represented. By collaborating with their parent or guardian organisation who knows them, we can reach an agreement that will avoid issues of safety, long-term harm and influence that might effect their development. This is not a straight-forward transaction, as demonstrated by the case of Spencer Elden who was photographed for the famous Nirvana album cover when he was a baby. Collaboration took place between the artist and his parents, but many years later Elden had a problem with the image. There are wider issues raised than a matter of ethics, with Elden being accused of indulging in the fame of the picture until that fame had diminished. Ultimately, his civil case regarding harm done to him was dismissed by the court. Where children are concerned, Collaboration in the form of open and honest discussion and consent to take a picture are key to avoiding any harm being done.

Conclusion

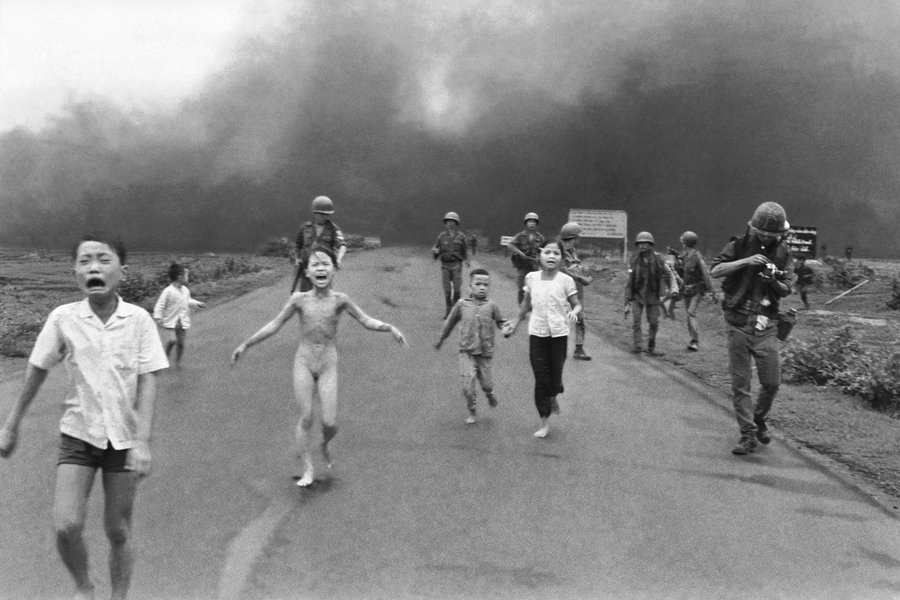

When I reflect on these principles, I see that they are closely interlinked and that they align with how I try to behave in other aspects of my life. The key learning point is that the camera doesn’t give us, as photographers, an excuse to alter our behaviour towards other people because it somehow anonymises what we are trying to represent. In the case of Napalm Girl, the photographer was employed to document the war visually, so when the attack on the villagers happened, his first thought was to shoot, what he saw. His instinct as a human being was to help the children, in particular Kim Phuc, who was in the most danger. He is credited with saving her life, which in my view balanced the decision to shoot first, help second. What Ut could not have been fully aware of, nor could he control, was the way the image was used for the next 50 years. He probably wasn’t aware what damage he would cause Phuc psychologically during her formative years, through the embarrassment of her nudity and vulnerability. In their case, a strong relationship formed after the fact, which would have provided both with insight into the impact of the decision to shoot and the impact it would have for both of them. When we look at the NAPP ethical values as an organisation, we can see that Ut did behave in an ethical manner. That may not have been how the world saw it when the image was published, but I don’t see how a conflict photojournalist could predict that in the decisive moment that presents itself. I was interested in the evolution of the Ethics Center and the concepts that were at odds with the historical video of Bruce Gilden. Gilden proclaimed that he had not ethics and that photojournalism was all ego, something he later retracted as being sarcasm. I personally think his comments at the time were the accepted norm and that history has rewritten the norms. If we consider how his approach to work would be received today, in an era where everyone has a cameraphone and everyone is being photographed largely without their consent, it stands to reason that modern ethics has had to remind photographers what their responsibilities are to their subjects and stories. For me, the experience of street photography is governed by my own ethics to the extent where I avoid it as a genre. This isn’t a positive situation either, as an artist shouldn’t be self-governing to the extent that they don’t produce work. I’ve self-edited to my detriment in this course previously [2], and having conducted some preliminary research into ethical practice, I would approach the shoot differently. My particular issue centred around not wanting to publish images that might cause my subjects issues (causing harm), but could have been offset by clearer communication (open and honest), which might have steered the work differently, but prevented my wanting to keep it from being viewed.

In summary, I am interested to see how my ethics change, if at all, as I progress through this module. What I’ve learned so far has made me think about my approach to work in a different way, so it will be interesting to see how that affects my future work.

References

[1] richardfletcherphotographyblog (2021) Assignment One: The non-familiar. At: https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/04/11/assignment-one-%e2%80%8bthe-non-familiar/ (Accessed 02/04/2023).

[2] richardfletcherphotographyblog (2021) Assignment Two: Vice versa. At: https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/06/25/assignment-two-%e2%80%8bvice-versa/ (Accessed 02/04/2023).(Password: Leitz1957RF)