The Brief

Create at least two sets of photographs telling different versions of the same story. The aim of the assignment is to help you explore the convincing nature of documentary, even thought what the viewer thinks they see may not in fact be true. Try to make both sets equally convincing so that it is impossible to tell which version of the images is ‘true’

Choose a theme and aim form 5 to 7 images for each set, depending on your idea.

Send your images to your tutor by the method you’ve agreed. Include an introduction of 300 words outlining what you set out to do and how you went about it. Also, send the relevant pages of your learning log or your blog url.

Introduction

I started thinking about this assignment shortly after reading through the course notes for the first time. I had been working on a long-term project which would document the decline, battle for survival and beginnings of rebirth of the high street in my home town of Malvern. Over the 20 years I have lived here, there have been huge changes to the retail and recreational landscape of this old town, whose roots were established during the Victorian era. The changes from that time were significant as Malvern was then considered a destination for health and wellbeing. The Victorians believed that the spring water from its hills was a cure for common ailments, so along with the desire to walk in the countryside that inspired Elgar, people flocked to the town to ‘get well’. The more recent changes though, have been as a result of the shift from traditional high street footfall to the online shopping model and an age where everything can be purchased in one giant supermarket. The town had become a place where only national chain cafes, restaurants and charity shops are the only places that could survive; the latter benefitting from vastly reduced rents. However, there are some signs of revival, with independent specialist shops opening up to serve niche markets. This evolution is slow and gradual, which meant that my project was probably not going to work for this assignment because of how long it would take to complete.

When I came to actually plan for the assignment, the world had been plunged into a crisis, the like of which hadn’t been seen since the Second World War. Coronavirus originated in China towards the end of 2019 and by the beginning of March 2020 had taken hold in almost every country on Earth. Life had changed immeasurably during that period, with most countries introducing strict lockdown measures that restricted the movements of their citizens. Every way of life has been affected and businesses have had to react quickly to survive. In my own company, all personnel that can work from home are now doing so, which presents its challenges, anxieties and impacts on family life. My team of 25 comprises families, single people, those with physical and mental health vulnerabilities. My daily challenge with the team has been navigating the fear and anxiety that the virus has created, focussing on what is important to them while maintaining control over the business. During our daily calls, we talk about the news coverage, the panic-buying and social distancing that have become everyday life for all of us. This got me thinking about my how the current situation has more than one side to the story. For every tale of the speed of the virus spreading and how people are acting irresponsibly, there are numerous stories of positivity, gratitude and solidarity during what is an unprecedented, horrific time.

My Theme

I decided to choose a statement the describes, perhaps controversially my perspective on the experience of the coronavirus lockdown. My first set would support the statement and the second present the counter argument. I was inspired by the work of both Gideon Mendel and Paul Seawright as two things resonated with me during the work in Part 1. The first was Mendel’s use of traces of the event in his work in the immigrant camps [1]. His use of possessions to tell a story about the owners without them actually being present was documentary in the way that we could relate to the objects, but built around a specific context that resonated with the artist. Seawright’s Sectarian Murders [2] was hugely powerful to me as the context was layered with news reports, themselves steering us towards a particular narrative. Yes, the blame wasn’t specifically apportioned in the works, but the documentary of the horror without historical context (the causes behind each event) leaves the viewer with their own take on the Northern Ireland conflict. As Seawright said in an interview, using too few contextual points leaves too much room for narrative and too many leaves the viewer with nowhere to go. For my series then, I would not be using anything that specifically referred to the virus or the lockdown, only imagery that includes the context and space to allow the viewer to create their own narrative. My take on the brief is that the two sets of photographs will have a sense of duality about them, making it difficult to understand what is happening or determine if the ‘truth’ is being told.

For my theme, the statement is “Coronavirus is changing society for the better”

Ground Rules

I set out with some simple ground rules for the images for this assignment and how they would be presented. They were as follows:-

- There would be no visual references to Coronavirus or COVID-19 in the images. As with Mendel’s work [1], the contextual details in the image would only suggest that something has happened/is happening.

- I would include people, but not exclusively. As this theme was a take on the changes to society, it would be easy to simply depict people in their new environment.

- I would present them as a jumbled collection with no external context applied to begin with. This is how I viewed Seawright’s work and was startled by how the addition of the simple contextual paragraph changed my perception of them. I would not give them names or numbers at this point.

- I would then add a two word context to each image to split them into their supporting and contradicting stories and review how effective they are as a document of these unusual times.

- Each image would be the colour and the same crop. Since I believed in Exercise 3 that black and white was able to actively assign a mood to the images, I would avoid its use. I naturally tend towards landscape format with an 8×10 crop, probably because of my connection to film. Making them all the same would avoid any distracting elements that steered the viewer one way or another.

The Unordered Images

Initial thoughts

Since starting this degree course, I’ve noticed a need that I’ve developed for making sure that the elements in a photograph work with each other. If something is superfluous and doesn’t connect with my vision of how I want the photograph to look, I generally discard and reshoot if possible. Of the images here, only one of them is staged, while the rest were observations during my government-sanctioned daily walks. I’m happy that the set contains no distractions or jarring compositions to begin with. As we’ve been blessed with glorious weather during this work, I don’t believe there to be any context created by differences in the light either.

Applying the Context

Here are the images again, presented individually with two word context added in the form of a title.

-

-

Smile, People

-

-

Business Attire

-

-

A Promise?

-

-

Nature Reclaims

-

-

Socially Distant

-

-

You ok?

-

-

Behind Bars

-

-

Little Choice

-

-

Great Outdoors

-

-

Grateful Patients

-

-

Thwarted Dream

-

-

Faded Art

-

-

Peaceful Parking

-

-

Typically British

Now we have some clearer ideas about the intended message behind this photographs. From this, they can be grouped into their supporting and contradicting sets:

In support of…

-

-

Smile, People

-

-

You ok?

-

-

Great Outdoors

-

-

Grateful Patients

-

-

Nature Reclaims

-

-

Peaceful Parking

-

-

Typically British

Contradicting…

-

-

A Promise?

-

-

Socially Distant

-

-

Behind Bars

-

-

Little Choice

-

-

Thwarted Dream

-

-

Faded Art

-

-

Business Attire

Review – Intent vs. Alternative Meaning

Smile, People – We saw this camper van on the driveway of a house in a less affluent part of the town one evening. The whole street had put out smilie face and Jolly Roger flags in their gardens to cheer up any passers by. This simple smile gesture certainly made me smile, even though there is a sadness to the van that is going nowhere while we are in lockdown.

You ok? – One of the many negative things about COVID-19 is the queueing for food, which at the start of the crisis was further characterised by panic buying and stockpiling essential items. Standing in this orderly queue for the supermarket, the lady in from started a conversation with a friend she hadn’t seen since lockdown. They had their conversation over the barrier at a safe distance from each other.

Great Outdoors – I came across this scene of an elderly and young woman out in the sunshine carrying their shopping home. One of the positive elements of the lockdown is the encouragement of people to get some daily exercise following the government guidelines. Here we have two people of very different age groups combining exercise with the necessity of shopping. This could equally be a statement about isolation and vulnerability with the younger woman not obviously helping out the old lady.

Grateful Patients – Positive messages in support of the NHS have been everywhere, with weekly clapping and painted signs like this one saying thanks to the key workers. While not limited to the NHS staff, they have been the biggest target of affection. Here, the patients of a local care home are also thanking their carers. This could equally have been a comment about being locked down in a care home and just wanting to communicate with the outside world.

Nature Reclaims – With no non-essential work being carried out, Malvern’s own street art is being reclaimed by nature. Another positive impact of the virus has been the effect on nature, both wildlife and the wider drop in pollution. This could also have been about a lack of attention to the town; letting it get scruffy through lack of maintenance.

Peaceful Parking – This stretch of parking spaces is generally never empty. The effect of less people out in town is that the whole place takes on a peace that is only normally witnessed at night. It could also have been about the crippling impact of the virus on the local economy.

Typically British – One of the town’s many shops showed its sense of humour with the socially distancing bears. They started out 2 metres apart and then moved closer together with the addition of some fetching wartime gas masks. The masks themselves have a sinister appearance, which could be interpreted as part of the fear around the virus and the way that it has taken hold.

A Promise? – I shot this photograph because I noticed the juxtaposition of the advertisement that has slipped from its mount and the promise of being able to move in the summer. I wanted to capture the interrupted good intentions of the window display where clearly nobody was at work in the building to fix the broken advert. The pharmacy in the background actually relocated to another building before COVID-19 struck, but in this image it reinforces the impact of the virus on key businesses. The duality of this image is that its possible that the advert hadn’t been noticed by the staff and the combination of the good weather and the promise could be read as resilience in the face of the virus instead.

Socially Distant – On one of our sanctioned exercise slots, I followed my wife with the camera looking to capture the new behaviour of people deliberately distancing themselves from each other. In this shot, my wife walks into the road to avoid the lady with her dog. What I wanted to capture here was the matter-of-fact action taken by wife at this moment, almost ignoring the lady altogether. The message being that despite the context of the sunny day, the excited dog and the smiling lady, the act is one of coldness. In fact, the opposite is often true. In this case the smile was appreciation of the gesture and pleasantries exchanged. This is an example of a decisive moment not describing the sequence of events, but merely an instant where the internal context is the only thing we have to go on.

Behind Bars – The children’s playground in the Winter Gardens park was, for a while a place where people gathered defying the lockdown. Since then, it has been closed with warning signs all around the perimeter fence. As I had decided not to include specific references to the virus, I looked for a composition with just the sense of being abandoned. This image of the roundabout with hazard tape around it struck me as sad, with no children around to play on it in the sun. The railing lends itself to the sense of imprisonment. The image could have been something less sinister, though with the park being temporarily closed for maintenance ready for the summer weather.

Little Choice – The pubs and cafes are all closed, but public transport is still running for essential journeys to be completed. The sight of empty buses roaming the streets of the town with the stark ‘Stay Home’ message displayed is becoming all too familiar. I like the conflict in this image with the pub and view enticing people to gather to enjoy the weather against the fact that we cannot. With this image, though there is room in the context to create a narrative beyond the virus. The message could be part of an advertisement instead of a government instruction and because we cannot see into the bus itself, we cannot tell that it is empty.

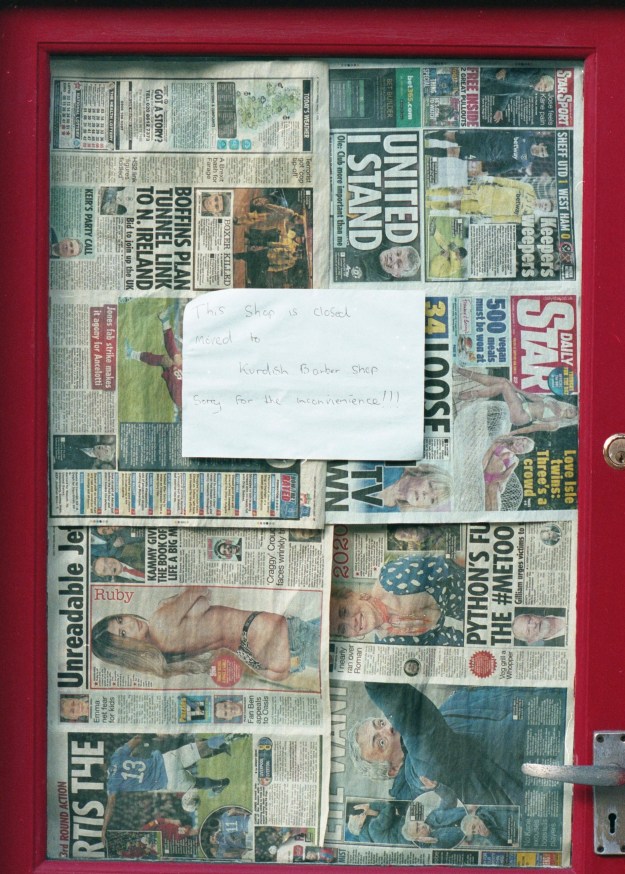

Thwarted Dream – This building is featuring in my series on the decline of the high street, but the shot I took for that was of a run-down, empty shop. In the weeks before the virus took hold, work started on turning it into the new business. This image without context could be interpreted as optimistic; the final step being the peeling of the transfer labels on the windows. If we look closer though, we can see that the works inside have barely begun. There is nobody working on the premises to get it ready to be opened. For me, the sadness of the image is that the virus may make the business untenable before it gets going.

Faded Art – This is an art installation by students of a local college that was created to brighten up the windows of the recently-closed department store in the town. Each installation has a colour theme and it has really lifted the look of the grand old building as it waits to be converted into new business premises. Here, we have a balloon display which in itself should be a joyful image. However, the building is empty and the helium has escaped the balloons. I wanted to capture the sadness of the way it had been abandoned, unmaintained and how the loaned balloons would not likely to be returned or reused. The image does contain am humorous inversion of that aspect though, saying ‘who thought that borrowing balloons was a good idea?’

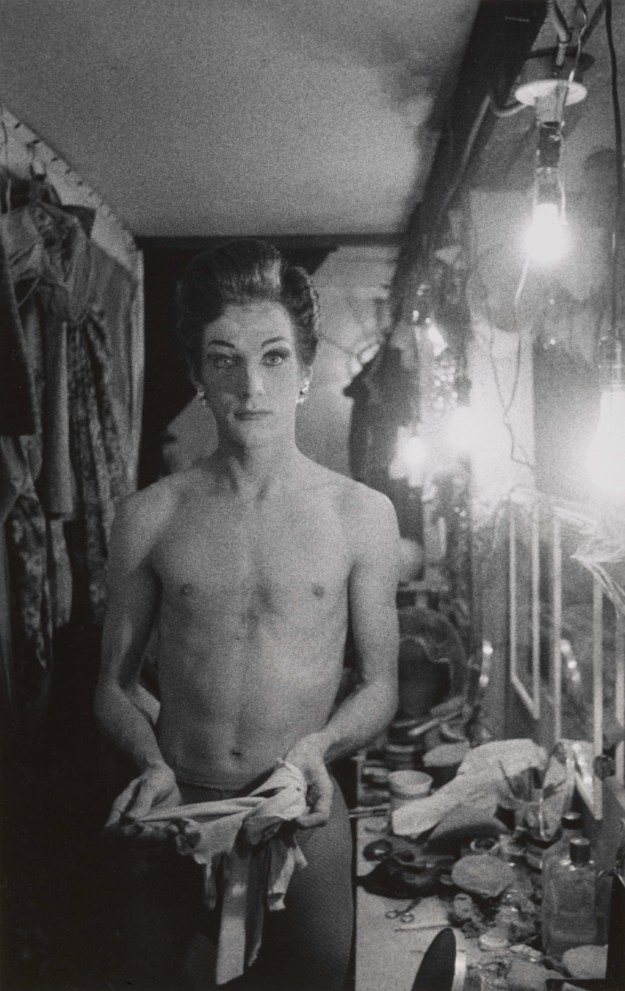

Business Attire – This image was spotted by my wife one morning as I started work. Working from home may have saved me a commute but the negative impact on my routine has become apparent. Here, I’ve not even bothered to get dressed prior to starting my first online meeting of the day. Although staged with a tripod and remote release, there is an honesty in the elements in the frame. The negative context is reinforced by the inclusion of the mug and the state of my dress. It could also be read as a relaxed way of working where there are no expectations other than performing in the job.

Conclusion

I really enjoyed this first assignment. The question ‘can photography be truthful?’ was one that I had not asked myself before Part 1, but the artists that we looked at offered an insight into its subtle exploitation for documentary or art purposes. With my collection, I feel like the duality of photography as a document is shown clearly. The situation we find ourselves in with COVID-19 is unprecedented and for the main, terrifying. However, one of the earliest realisations that I came to was that forcing people to change their lifestyles and stay away from each other would have a positive impact on society as a whole. As a photographer, being limited in the places I could visit because of lockdown actually made me look harder for that positivity which resulted in my capturing more of it. I actually struggled to find compositions that were overtly negative to be the greater challenge. I am happy that my interpretation of the brief works; there are two sides to the story and part of that is being unable to obviously tell the difference. By adding the simplicity of two words as a title, the narrative comes quickly. If anything, even something as simple as that leads the viewer too readily to a narrative. A change I would make to the series is to make the titles more obscure.

What went well

The strongest image for me is Typically British as I like the clear sense of humour mixed with the gravity of the situation. Humour in photography has become something that I’m drawn to when times are difficult; a kind of self-medication, I guess. The sinister side of the photograph is the thought that not even our teddy bears are safe from the virus. Giving them WW2 gas masks emphasises how dangerous the infection could be. For a simple composition, I think it tells both sides of the story effectively.

The other strong images for me were Behind Bars and Socially Distant, both of which provoked a negative reaction in me. In the former it had not occurred to me that this happy space which is very popular with the town’s children would be abandoned. Seems obvious, but its impact on me was profoundly sad. I definitely felt like Soloman-Godeau’s outsider trying to capture this scene. Socially Distant was also a sad image for me as the dog in the photograph came towards me for some attention, but I was distracted by my wife’s exaggerated deviation from the path. Under normal circumstances, the dog would have been made a fuss of and pleasantries exchanged. This situation is clearly not normal and that comes out in the photograph. Unlike Behind Bars, I was an insider in this shot.

What could have gone better

The weakest image for me is Business Attire because it is not as candid as the others. I wanted to use natural light for the shot to ensure that there were no harsh reflections from the shiny surfaces on my desk. This meant that I needed to use a tripod and tethered remote. I think the sentiment and duality come out in the image, but for me there is a sense of overt context. The inclusion of the Mr Grumpy mug, on reflection is too much of a sign-post element in the image.

Also, I would consider re-visiting the titles themselves as even though they are short and seemingly simple, they point very clearly to the intent behind the image. Before I added them, I showed the collection to my wife. Her interpretation of the context differed only slightly from my own, which I conclude is because we have been married so long coupled with her sharing my photographic ‘journey’ so far.

Getting Feedback

My intention was to share more widely to see which sides of the story are being ‘told’ and, more importantly, whether people believe my statement that we will be an improved society when the danger of coronavirus passes. I sent the unallocated images to a small group of my photographer friends with simple numerical titles and asked them to arrange in the supporting and contradicting groups. I deliberately asked them not to confer or share their thoughts on the meanings of the images with each other and perhaps unsurprisingly, some found the job of grouping them a challenge. To make things more difficult, I told them that I wasn’t all that interested in their explanation of the narrative created for each image as discussion would have helped them form a view that was influenced by my intentions for the series. The results were as shown below:

Results of Review of the Unallocated Photographs

What struck me first about the results was the strong agreement with my intention for the images of the playground, the NHS thank you and the unfinished shop front. These images were strong with elements that steered to a great sense of sadness or extreme happiness. The ‘negative’ images were almost signposted to contradict my story, so using photography to effectively prove a lie. The next thing that stood out was the balance in some of the responses, i.e. in two minds about what the photographs say to them. In these photographs, the story about the improvement in society comes through but with an equally opposing feeling created by the knowledge we have about the pandemic. Socially Distant is a good example of this. I felt that we were losing personal contact, but three people thought differently. Perhaps the act of social responsibility caused by the distancing in the image supports that we actually care more for each other with the current restrictions. The final observation was where the consensus was generally in disagreement with my original intent. Looking back at the earlier research in Part 1, I was reminded of how our perspectives are built on our personal circumstances, beliefs, biases and the previous events in our lives. Four of the people asked are living in urban environments where the virus is affecting many people in a confined space. Their views on the images are naturally going to differ from the other two (and me) who live in a more rural setting.

Overall, I am happy with the way this assignment has gone. In Part 1, I’ve learned the difference between being part of the story and an observer, how photographs are used to get a message across that is not always truthful and that there are many different versions of what is the truth. With the ghost photography of the late 19th Century, the trust in photography as an honest viewer of events was severely tested, with the foremost intellects being conned by photo manipulation. Where documentary fails though, art becomes the destiny for photography ‘stories’. Powerful messages about society like those in Dzhangal and Public Order don’t need to rely on facts to have impact. Perhaps objectivity is not all it’s cracked up to be.

References

[1] Mendel, G, 2016, Dzhangal Work, Artist’s Website, http://gideonmendel.com/dzhangal/

[2] Seawright, P, c1970s, ‘Sectarian Murders’, Artist’s Website, http://www.paulseawright.com/sectarian