Introduction

We are introduced to a number of artists who have elected to take the ‘bring your imagination’ to their work. Where the previous artists had represented their subject’s identities in the context of daily life, their real or imaginary environment, the next idea being investigated is when the subject is absent. In the first Research Task [1] we consider how removing the subject affects the photographer’s role as documenter or storyteller, as well as thinking about our own thoughts on how it might affect our work going forward. In this post, I will be looking at the artists themselves.

William Eggleston (1939 -)

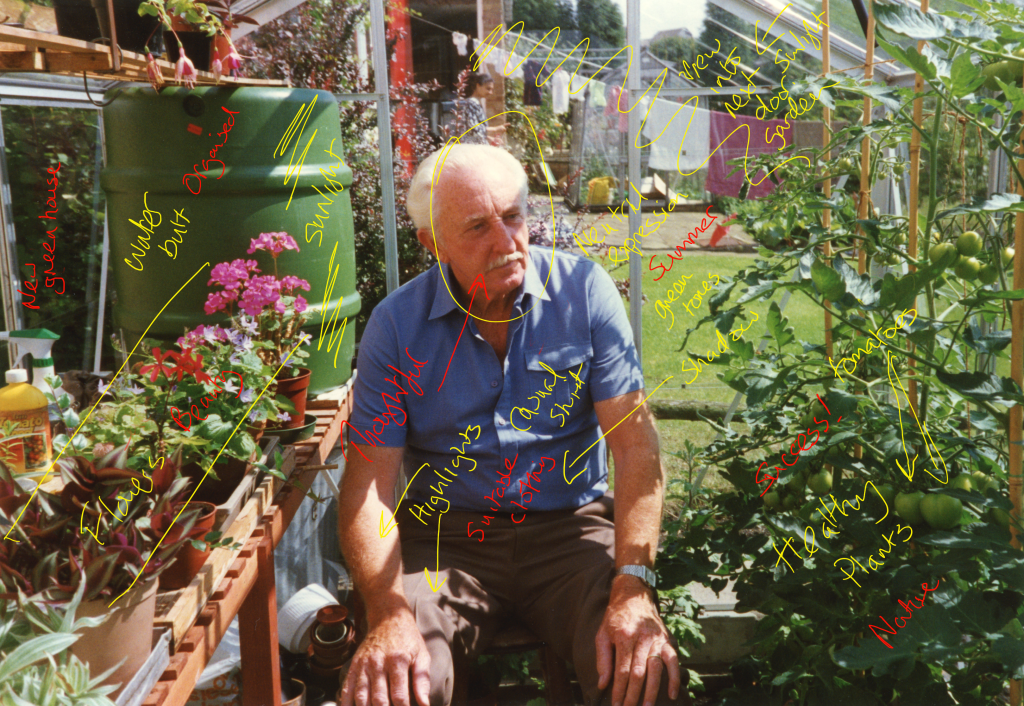

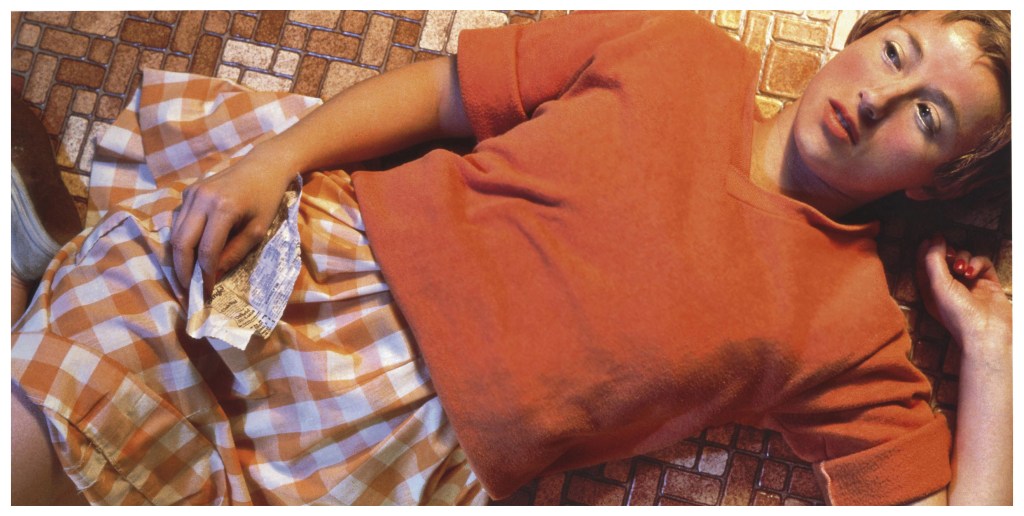

William Eggleston is a photographer that divides opinion. His work is considered pioneering and overrated, seemingly in equal measure, but one thing that anyone would struggle to do is ignore it. The notes refer to the duality of his shooting a particular place that we may or may not be familiar with and representing it in a way that the viewer has to decide how real or not that may be. Perhaps his most talked about photograph (below) is a great example of this.

Here, the child’s tricycle looks like it has seen better days and is apparently abandoned at the side of an ordinary-looking street. In an interview with the Whitney Museum [3], Eggleston refers to his walking around an ordinary neighbourhood in Memphis without any particular purpose. While sitting on the curb, he noticed the tricycle close by. His photograph puts the viewer at the same level as his subject and it dominates the frame. We cannot help but look at the tricycle as if from a child’s perspective. Why was it left there? What happened to the owner? More importantly, the viewer is encouraged to look beyond the dominant subject at the background. The street looks fairly featureless, but the questions about the neighbourhood are instant. What is the place like? Do people litter the streets with stray children’s toys? We know nothing really about the street or its inhabitants, but Eggleston creates his own version of it through an image of an everyday object in the context of its environment. It’s condition and the fact that it is left out on a pavement lets us draw our own conclusions about it, based on our experiences, prejudices and cultural view of the South US. Eggleston claims that he just likes taking pictures of what he sees, but in looking at his work, there is a great deal more to it than that. In his book Election Eve (1977), he shoots a series of pictures that refer to traces of the subject alluded to by the title, but in reality it’s more about small town American life away from the hysteria of the election. In most cases the images show only traces of the people in the town, with those where we can see them are composed in a way that doesn’t distract the viewer to the other elements in the frame.

In this image, Eggleston creates a sense of rural America through his use of colour and tone. The use of colour is something that Eggleston is famous for as one of the pioneers of its use when high art was still firmly in black and white. Here, the rich brown tones of the porch and the car are made vivid by the film and the light in the scene. The mood that Eggleston creates is a clash with the urban aesthetic that we would naturally associate with Washington, where the presidential election was taking place. The image, and indeed the series, suggest a ‘meanwhile, away from the noise’ response to the events. Eggleston includes traces of people in this frame (the car, the deckchairs on the porch etc) and also someone on the very edge of the frame. By leaving the woman half in the composition, Eggleston gives the sense that the people of this rural area are somehow unimportant.

“On the eve of the election, when nothing had yet been decided, when everything–whatever that everything was–hung in the balance, Eggleston made an elegy…a statement of perfect calm. To say, however, that these photographs are romantic, sorrowful and quiet is not to imply that they are easy or in any sense comforting. They are richer and more sensual in some ways than Eggleston’s other work, but they are not less penetrating or unsettling. In them Eggleston seems bent, as always, on recording those unremarked units of spatial perception by which the everyday world is unconsciously ordered”

Lloyd Fonvielle writing in the introduction to Election Eve (1976)[4]

Richard Wentworth (1947 -)

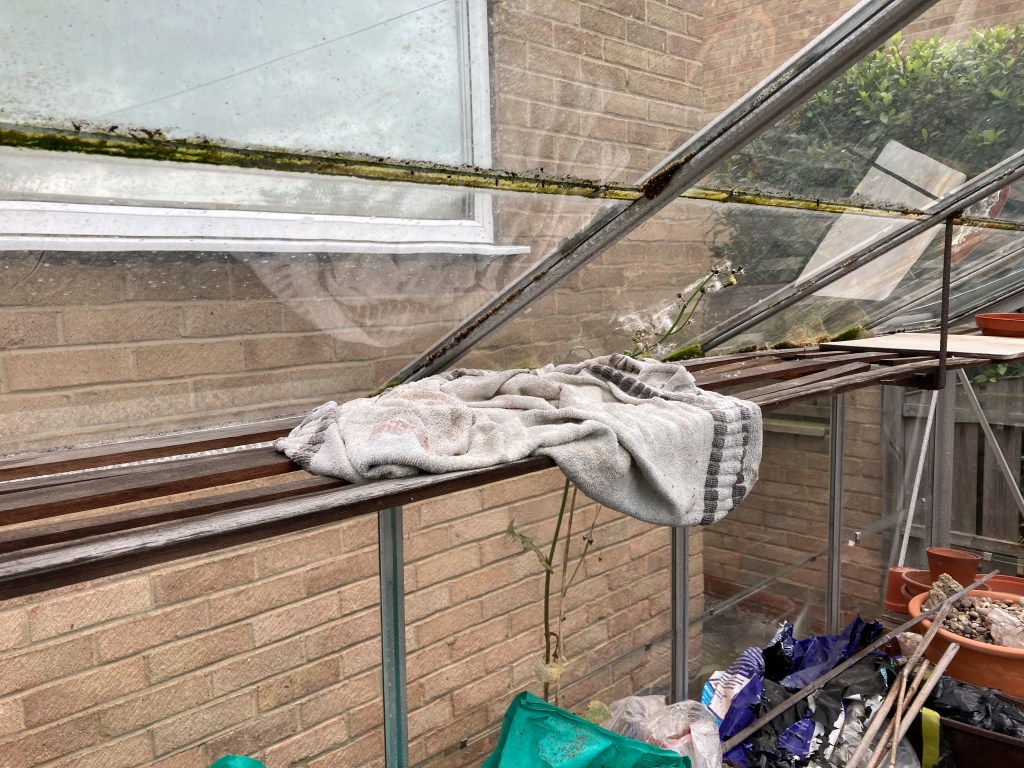

In his book Making Do and Getting By (1984), Wentworth presents everyday banality in the same way as Eggleston, only here we have traces of people doing the best they can with whatever is available to them. In a humerous way, Wentworth’s series looks like a collection of badly executed DIY repairs, ranging from the hoarding around the base of the lamp post shown in the notes to the use of the hammer to lift a door off the ground. There are a number of layers of narrative in these works, staring with the obvious poking fun at the ineptitude of what cases of ‘making do’ with botched repairs. However, we also see situations created by people who have little choice as in the image below.

In this picture we see a ladder precariously balanced on blocks of chipboard. Aside from the perceived stupidity of the arrangement which looks dangerous, we also wonder how the operator concluded that this was the right way to go. Did they have no other alternative or is this the reality of working in the city vs. the countryside? We cannot see the operator and don’t know if they used this setup or not. The picture asks questions of us as a resourceful species, the societal aspects of what is acceptable risk and of the person taking that risk, despite there being nobody in the photograph. In addition to these interpretations, the image is a 2D representation of what could be a modern art sculpture. In the banality of the composition, Wentworth creates a simple but challenging narrative that combines the serious with the satirical. Like Eggleston, Wentworth takes his time to observer, citing the artist’s responsibility is to be vigilant [6]. In looking for the things that we might not notice in the chaos of daily life, both artists create a commentary on an aspect of society that we are all familiar with, even if we are not within it.

Elliott Wilcox (1987 -)

In Wilcox’s work we have much more abstract traces of human life. Both series are shot with tight fields of view which result in shots that ask questions about the subject itself. In Courts his shots of a Real Tennis court, a game popularised in the Tudor era, offer the viewer a perspective on a space that has a vintage feel to it.

The inclusion of crowns painted on the walls suggest that something important or upper class takes place on the court, which in turn sets the space into a societal context. When we look more closely, we see the marks left by the tennis balls striking the once-pristine paintwork. In other images, there are cracks in the surface which future emphasis the sense of intensity in the sport. This points to the passage of time and the vast number of people who have competed in this space. We get sense of the activity and the people taking part without them needed to be there. The notes refer to his other work ‘Walls’, which takes the same approach with a variety of climbing walls. the tight compositions accentuate the minute traces of people left on the walls, but the subjects themselves are often obscure to the point of becoming abstract.

Sarah Pickering (1972 – )

We’ve encountered Sarah Pieckering’s Public Order series in a previous unit[8]. Her bleak architectural landscape shots of a fake town that is used to train police officers in public disorder management are strange but familiar. At the time, I associated the work with the familiar aesthetic of the area where my wife grew up in industrial West Yorkshire. I was considering Pickering’s use of the space, texture and implied dereliction of an urban area, but when I think about it now, I re-evaluate what I brought to that original interpretation. If I were to walk around the area that I am familiar with, I would see the features of the environment in the context of the people who live there, which would in fact tell a story about everyday life. That everyday life would include not only the physical decline, but also the changes in cultural influence. I would be able to see positives and negatives within that area’s identity. When I look at Pickering’s work, however, there is no reference to actual people. We are presented with a visual where we create our own population that might inhabit it. That creation is based in ‘fact’, i.e. what we bring to the reading of the image, but also has a fantastical element to it.

With her other work Incident (2008), I am instantly reminded of the work of mid-20th Century crime photographer Weegee, who for many years turned to crime scenes with his large format press camera to shoot the immediate aftermath of a heinous crime. In those images, the scene was often ‘managed’ in some way by the police presence, which leaves the viewer wondering with many questions about what had just occurred.

In this image, we see a police officer and another man looking at a covered body on what looks like a pier. The actual story is of a stampede that killed the woman lying on the ground and we see on further inspection that the wasn’t the only one. However, without the knowledge of the story, we are left with questions about the victims, whether they were linked to each other in any way as well as the obvious ‘what happened here?’ Weegee included enough to suggest documentary, but left enough room for the viewer to make up their own story that fitted the elements in the frame.

With this image we see a collection of burnt out white goods. At first the damage points to our inner fear of a fire breaking out in our homes, but on closer inspection the items don’t appear to be severely damaged. The soot that covers their surface came from another part of the building, which leaves us wondering about what happened. The domestic nature of the image suggests, but doesn’t specifically include people as with the other artists here. We recognise the machines as part of our daily lives which are now in some way unavailable to the owner. As well as the big questions of whether the people managed to survive the fire, we are also wondering how their lives will need to be rebuilt, starting with these appliances that they/we depend on daily. Of course, the series isn’t about any real people, instead being a training exercise for firefighters. By including familiar objects and linking them with our primeval fear of fire, Pickering creates an anxiety where we hope that our imaginary occupants made it out alive.

Conclusion

The artists in this project have succeeded in making work about people, whether real or imaginary, without any being present in the images. By using subjects that point to some event or activity that people might participate in, the viewer is given a sense of who the absent person might be. However, in leaving the space to create our own impressions the artists make the work more about how we imagine life to be rather than limiting the reading to our own experiences. As Szarkowski pointed out in his introduction to Eggleston’s work, the idea of the picture being more than just an assumed reflection on real life means that there is a great deal more to connect with when we view it. When this happens, the apparent banality of the subject is in fact the art, rather than a statement of fact. For me, the suggestion of identity though the use of traces gives a freedom to the work for which there is no right or wrong interpretation.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2021, “5) Exercise 1: Personal Reflection”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/11/16/5-research-task-personal-reflection/

[2] Eggleston W, 1969, “Memphis”, Image Resource, MoMA, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/51630

[3] Sothebys, 2021, “Election Eve: 50 Masterworks to celebrate 50 Years of Sotheby’s Photographs”, Image Resource, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/50-masterworks-to-celebrate-50-years-of-sothebys-photographs-2/election-eve

[4] Editorial, 2010, “William Eggleston: Preface from Election Eve (1977)”, American Suburb X, https://americansuburbx.com/2010/09/william-eggleston-preface-from-election.html

[5] Unknown, 2019, “Richard Wentworth”, Exhibition Catalogue, XIBIT Magazine, https://www.xibtmagazine.com/en/events/richard-wentworth/

[6] Phaidon, 2015, “Akademie X:Richard Wentworth”, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jsivEAXRwg

[7]Unknown, 2021, “Elliott Wilcox – Crane Kalman Brighton, Gallery Brochure, https://cranekalmanbrighton.com/artists/elliott-wilcox-biography/

[8] Fletcher R, 2020, “Exercise 3: Public Order”. OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/05/12/exercise-3-public-order/

[9] Unknown, 2012, “Shot Dead: Weegee’s murder photographs go on show – in pictures”, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2012/jan/19/weegee-murder-photographs-pictures-new-york

[10] Pickering S, 2008, “Incident”, Image Resource, Artist Website, https://www.sarahpickering.co.uk/works/incident/