Project 2 concludes with the portraiture work of three other photographers, two of which I have researched for previous modules on this course. Arbus was well known for her almost voyeuristic photography of people she found interesting. Mapplethorpe’s work gained controversy because of his exploration of sexual identity through images that were considered explicit. While I looked at their work from the perspectives of street photography and censorship previously, here I will look at their portraiture in the context of Part 1.

Diane Arbus (1923–71)

In 2018 I went to an exhibition of Arbus’ early work called In the Beginning at the Hayward Gallery in London [1]. The works in the exhibition were of a variety of subjects, from her portraits of the wealthy to the circus freaks of New York. What interested me at the time was the connection that she appeared to have with her subjects. Unlike many photographers, Arbus’s style involved engaging directly with her subject. Sounds pretty obvious when we think about portraiture, but Arbus’ photographs were very much brief interludes into the lives of her subjects; they were almost snapshots of people living their daily lives. Yet, like Sander, she was drawn to particular types of people and contexts. In a video documentary by her daughter Doon Arbus, the photographer Lisette Model described her typologies as being “freaks, homosexuals, lesbians, cripples, sick people, dying people and dead people” [2]. She went on to describe the reason for this darkness being the fact that people were not comfortable looking at these types of photograph. Model believed Arbus to have great courage in her depiction of these marginalised people and to show them as being ‘normal’ in every respect of their lives. This was a point that was famously disputed by Susan Sontag in the chapter America, seen through photographs, darkly in her book On Photography (1973)[3]. Sontag responded to similar claims about Arbus made following her tragic suicide in 1971 at the age of 48 and the subsequent retrospective of her work at MoMA. Sontag’s view was that far from being a sympathetic perspective on the marginalised, Arbus’ style of engaging with the subject so that they looked directly at her or her camera was almost voyeuristically exploitative. When viewed alongside the work of Nan Goldin a few years later, which dealt with some of the similar sections of society, I can relate to what Sontag meant. Goldin was shooting her friends and housemates in a way that not only naturally placed her as an insider, but highlighted the love that people had for each other and for their way of life. Arbus, by contrast posed her subjects in a particular way and although there are stories of her trying to blend in with them , for example she photographed naturists on a nudist beach by stripping off and joining them, Arbus was still on the outside looking at what we all consider to be different. Nevertheless, I reflect on the exhibition in London fondly as she definitely revealed something powerful about her subjects, even if there was something forced in the aesthetic.

Robert Mapplethorpe (1946 – 89)

Much has been written about the controversy surrounding Robert Mapplethorpe. His story of joining a youth culture that centred around the famous Chelsea Hotel in New York, which led to artistic and sexual experimentation, is well documented. His progression into what people considered to be obscene photography or pornography became the subject of a criminal prosecution [4]. Although I’ve looked at his work before and some of these problems that still surround it, I was more interested for this project in looking at how he got started. Mapplethorpe shot many different types of subject, but his portraiture has a definite use of typology running through it.

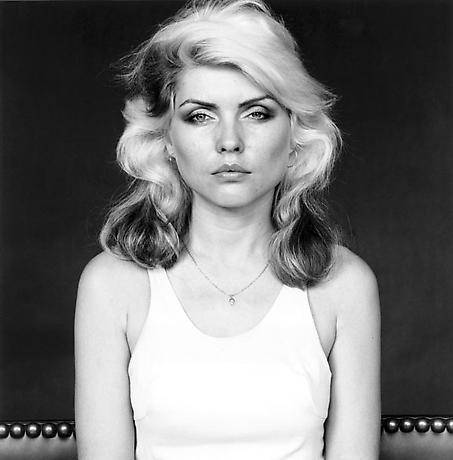

Mapplethorpe started out as an photo artist that produced his work from that of others. The American philosopher Arthur C Danto described Mapplethorpe’s early ‘career’ as being as a photographist [5], which placed him very much in observation of how people were represented by other photographic artists. Danto identified the point at which Mapplethorpe transitioned from photographist to photographer; in 1970, Mapplethorpe purchased a polaroid pack-film camera and began experimenting with it. His early exploration with this camera started with the people and objects that were closest to him, often shooting pictures of his then lover Patti Smith as well as men with whom he would start to explore his sexuality. The resulting photographs started to fall into particular typologies such as self portraiture and his body image. He depicted himself as the rebel or as some kind of sinful creature, as well as exploring how he looked in drag. His interest in his own body became the start of his more explicit work, often depicting his penis as in the famous self-portrait in the mirror [6] and in sado-masochism constume. He started to expand the subject matter to others but still represented his subjects along very specific lines. Some photographs were of his lovers, others of people he picked up of the street, while some explored race and homosexuality and the difference between how bodies look. As Mapplethorpe became more well known and progressed to better equipment, his work continued to follow the representation of cultures and practices that were not regularly discussed or acknowledged by most people. The results were indeed shocking, but for me Mapplethorpe represents originality in what is essentially his documentary of the life he was living and the beauty that he saw around him. Some images are extremely uncomfortable to look at because the sexual act being depicted is not commonplace, but that doesn’t make it any less representative of the world he lived in. His work wasn’t just sexually explicit though, as Mapplethorpe also shot portraits of very famous celebrities of the time. It is here that we see his use of background in a similar way to the previous exercise. Take the example of Debbie Harry, shot in 1978:

Here we see the Blondie singer seated on what looks like a sofa staring straight at the camera. The composition is complete symmetrical about Harry’s strikingly beautiful but angular features. What is interesting here is not so much the subject but the background. Mapplethorpe shot this in his studio with a black backdrop, which creates a lot of contrast with Harry’s skin and hair. The dress was apparently light blue which blends in with the rest of the subject’s luminance. The only other detail is the studded top of the sofa which can be seen either side of her. In this one simple background detail, Mapplethorpe creates a sense of what the model is about. Harry’s rockstar looks are reinforced by the metal studs and seemingly leather covering of the sofa. Even though the background occupies a very small region, the effect of it in the image is very strong.

Jason Evans (1968 -)

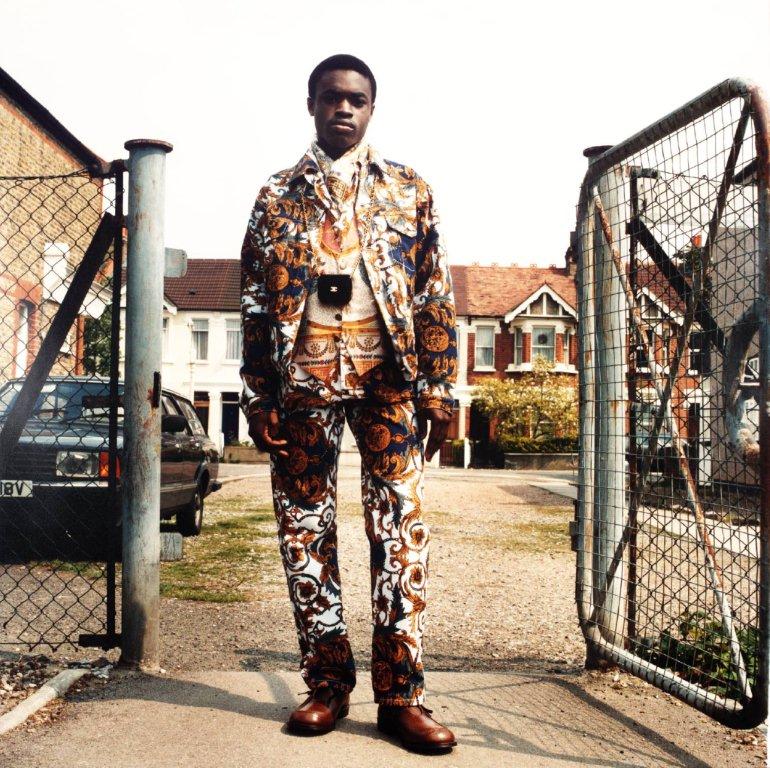

The final photographer mentioned in this section is Jason Evans. His work Strictly with Simon Foxton uses typology and background to deliberately tell a different story to what might be immediately present at first glance. Evan’s project was very much in the fashion genre, working with a well known stylist in Foxton and the photographs are indeed centred around the styles of the clothing used. However, the work is intended to challenge how we typically see the typology of traditional fashion. In the series, the models are all young black British men and they are dressed and styled in what we would identify as being fashion poses. However, the clothes they are wearing are the opposite to what we would expect young people would wear. Instead, the selections of outfits invoke a sense of the dandy, a style that is associated with 18th Century extroverts. The culture of the dandy itself is predominantly white, so by dressing black men in these ‘costumes’, the artist is creating a counter-culture. This distortion is made into a more social commentary by Evans’ choice of backgrounds for his work. Each man is posed in an environment that we identify with as middle-class suburbia. In a video interview with Tate, Evans described the environments as what we think of as predominantly white neighbourhoods [8] and although there is nothing explicit in any of the shots to reinforce this, the contrast between the subjects, their clothing and the environment is striking. Evans and Foxton use typologies such as black youth, stylised fashion and suburbia in a way that creates an unexpected narrative.

Here we have a young man dressed in a very striking, but smart three piece suit and polished shoes. He is standing in what looks at first like a comfortable pose that faces the camera. However, his hands look like they are not so comfortable as they are held awkwardly by his side. Their appearance suggests that the man is either not comfortable with the clothes he is wearing or having his portrait taken. In itself, the portrait reveals something about the man and contrasts his clothes with his age and cultural status. It’s when we look at the background that the additional context helps complete the narrative. The scene is a Victorian street in what looks like suburbia and there is relatively contemporary car in the middle distance. The man himself is standing in front of an open gate which suggests at first that he has just walked through it towards the camera. This contradiction between the young black man, his dandy clothes and the fenced off community behind him suggests all manner of prejudices and stereotypes about young black males.

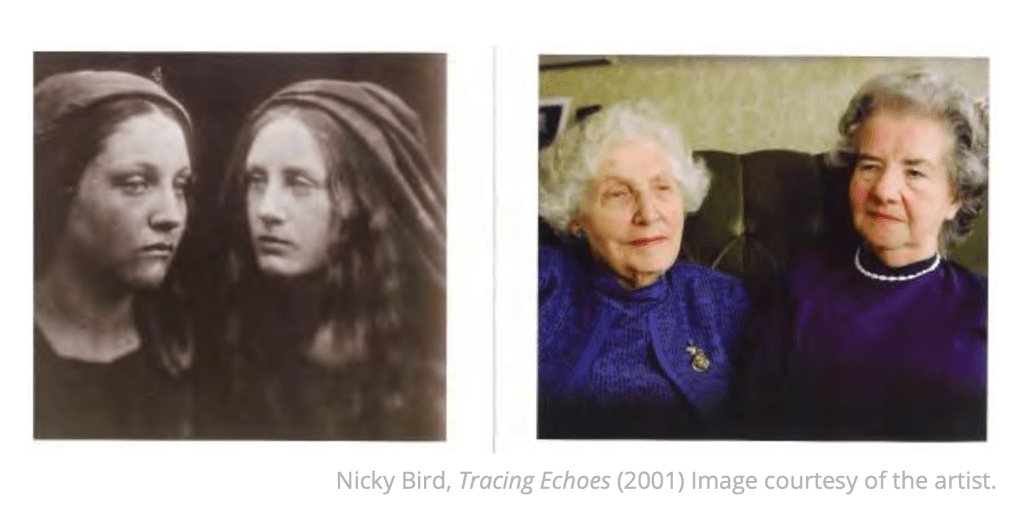

Although the compositions share similarities with Sander’s work with the face-on, natural expressions, the context that is brought by the background is much more aligned with the street photography genre. In the pictures, we see the young men in a pose, but was that the interruption of their routine by the artists? Is the contrast between their clothes and ethnicity really a challenge of stereotypes or is there such a thing as a contemporary dandy? If there is, which ethnicities would we associate with them? When I think about these questions, I’m reminded of Julia Margaret Cameron’s combinations of what we can discern from the subject’s appearance with another story that might not be all that it seems.

Conclusion

The work in this Project and Exercise 2 has demonstrated the use of both typology and background to add context to a portrait. Since we all naturally categorise what we see in some way, typology is a tool that the artist can use to lead the viewer to an assumption about the subject, but also to mislead as to the intended meaning. When confusion is introduced into the portrait, the variety of possible narratives about the subject increases. The work of Cameron in Project 1 was pioneering in her use of photography to tell stories about her subjects, but the work of the typology photographers such as Sander and the Bechers helps to remove the obvious and get the viewer to concentrate more on any context that is available. With Sander and his use of backgrounds and costume, we have someone who went on to inspire the other photographers here; Arbus with her fascination with the freakish underbelly of society that nobody wants to think of, Mapplethorpe with his self exploration and breaking of sexual taboos and Evans with his statement on stereotypes in race and class. I’ve found this project to be revealing in that it has prompted me to think more about the story than I would previously have done so when shooting portraiture.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2019, “A Tale of Three Photographers”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2019/07/26/a-tale-of-three-photographers/

[2] Jones J, 2014, “1972 Diane Arbus Documentary Interviews – Those who knew the American photographer best”, openculture website, https://www.openculture.com/2012/10/1972_diane_arbus_documentary_interviews_those_who_knew_american_photographer_best.html

[3] Sontag S, 1973, “America, seen through photographs, darkly”, from her book “On Photography”, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-7963-2699-8

[4] Palmer A, 2015, “When Art Fought the Law and the Art Won”, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-art-fought-law-and-art-won-180956810/

[5] Danto A, 2001, “Instant Gratification: Robert Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids 1970-1976” (republished by Aperture 2015), Aperture Magazine Essay, https://aperture.org/editorial/archive-robert-mapplethorpes-polaroids/

[6] Unknown, “Self Portrait, 1973”, Image Resource, Mutual Art Auctions, https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/Self-Portrait/148D8D4E23A4738D

[7]Unknown, “Debbie Harry, 1978”, Image Resource, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, http://www.mapplethorpe.org/portfolios/portraits/?i=2

[8] Tate Museum, 2017, “Jason Evans – Culture is Everything We Do – Tate Shots”, Tate Website, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/video/jason-evans

[9]Unknown 2013, “From the Series ‘Strictly, by Jason Evans and Simon Foxton”, Image Resource, A.G.Nauta Couture, https://agnautacouture.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/p11788_9.jpg