Introduction

The feedback from my tutor on Assignment 5 pointed out that I had limited my research to a small number of photographers that I admired and that I only included a single contextual reference, ‘Mirror and Windows’ by Szarkowski. I seek to address the depth of my research in this post by looking at a selection of the recommended photographers and artists from the feedback. The list of artists was as follows:

For the photographers Francesca Woodman, Robert Maplethorpe, Nan Goldin, Eikoe Hosoe, Sophie Calle, Sally Mann, Lu Guang and Yosuke Yajima. For the painters/sculptors, Warhol, Giocemetti, Munch, Bacon and Freud. I wanted to look at different ages, periods and nationalities in my selection to better understand the variation in attitudes as well as their creative style. As the need was to explore contemporary art, I was also interested to see how their style changed over their working lives. I selected Woodman, Hosoe and Goldin for the photographers and Munch and Giacometti for the painting and sculpture.

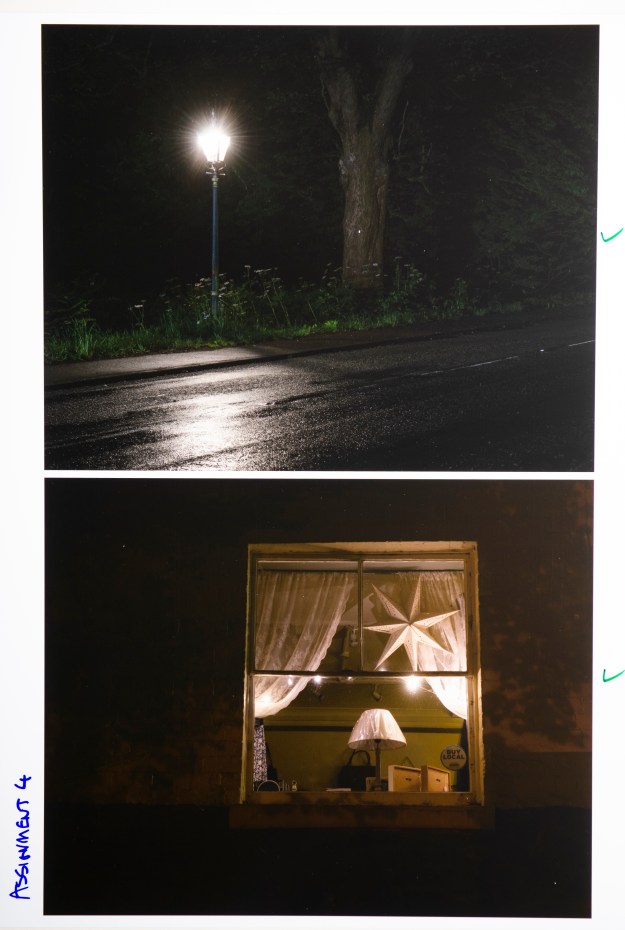

Francesca Woodman 1958 to 1981

I had heard of Francesca Woodman prior to the course but, like many the only real detail I knew was of her tragically short life that ended with her suicide in Manhattan when she was just 27 years old. She suffered from depression, like many people including myself and indeed many artists do. It would be easy then to make connections with other famous photographers who suffered in the same way, such as Diane Arbus or Bob Carlos Clarke. When we first look at her photographs, with her life as context, we see a woman who shot almost exclusively in black and white, used herself as one of the subjects of her images and was often in a pose of resignation or dark mood.

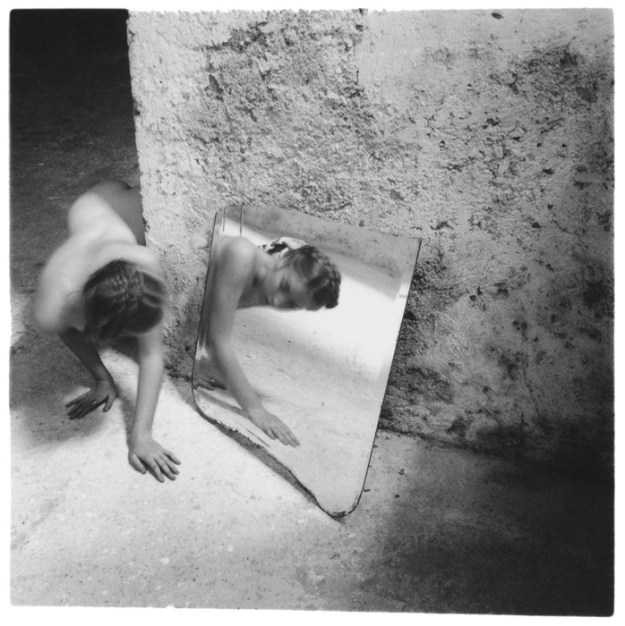

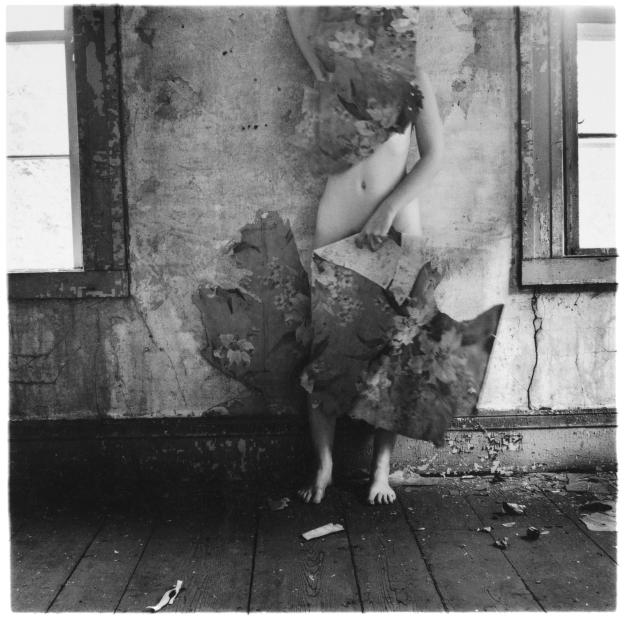

However, when we examine her photographic style we can see a number of themes that don’t always lend themselves to seeing her through that lens. Her self portraits predominantly feature Woodman and few other physical details. In many cases, her environment is rustic or run-down. In some, she appears with a prop such as mirror or a curtain. In many of her images, she appears nude and almost ghost-like through her use of long exposures and natural light creating movement and blur. Consider her two images Space 2, 1976 [1] and Self-Deceit #1, 1978 [2].

Self-deceit #1, 1978 by Francesca Woodman [1]

In this first photograph, we see Woodman prowling around the corner of a wall and catching her reflection in a mirror in a way not dissimilar to how a cat would. Her nakedness creates the impression of a pure creature with the only hint of her humanity being the styling of her hair. Her body blurs with the movement as she rounds the corner but we see the detail of her face reflected in the mirror that suggests her stopping to look at herself. What is interesting to me about this picture is the fact that although Woodman is the subject of a self-portrait, she isn’t the dominant element in the frame. The textured background and the contrastingly smooth mirror take up the majority of the frame, yet both draw the viewer to Woodman’s reflection and her expression of surprise, almost disappointment at what she sees. I struggled at first to understand the title of this photograph – what exactly is the deceit she refers to? On reflection, the context in the image points to our internal impression of how we appear and that, like a startled animal that catches themselves in a mirror, we realise how little our self image matches our actual image. In this case, Woodman is clearly young, but moving through a space that is old. Perhaps she had convinced herself that she was an old soul and the mirror is the reminder she needs ,that on the outside at least the opposite is the truth.

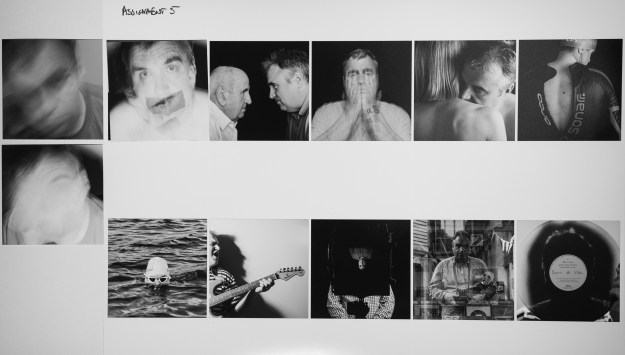

Space 2, 1976 by Francesca Woodman [2]

In the second photograph, we see at the same kind of decaying space where hints at its former elegance remain in the detailing of the skirting boards and windows. Woodman appears nude but mostly obscured by the scraps of wallpaper that the is holding. When I look at this picture, the immediate impression is of a young woman wanting to hide. I asked myself how much of this was owing to what we know about what happened to her. An interview with her parents [3] in the run up to

Zigzag, a collection of her work on angles and lines being shown in London, reveals a different side of her personality to the assumed norm.

“Their memory of Francesca is that she wasn’t a “deeply serious intellectual”; she was witty, amusing. “She had a good time,” says Betty. “Her life wasn’t a series of miseries. She was fun to be with. It’s a basic fallacy that her death is what she was all about, and people read that into the photographs. They psychoanalyse them” – Betty Woodman in an interview with The Guardian [3]

With this new information, I see Space 2 differently from before. Now I see the beauty of the contrast between her plaster-like skin against the decaying plasterwork and the suggestion that this somehow brings the space alive again. Her use of the wallpaper takes the focus away from her as a woman, while playfully showing just enough of her form; the whole image taking on more of a game of hide and seek. Whatever the intent behind Woodman’s self-portraits, the enigmatic style in her compositions differs considerably from the photographers that I’ve previously researched.

Eikoh Hosoe 1933 to present day

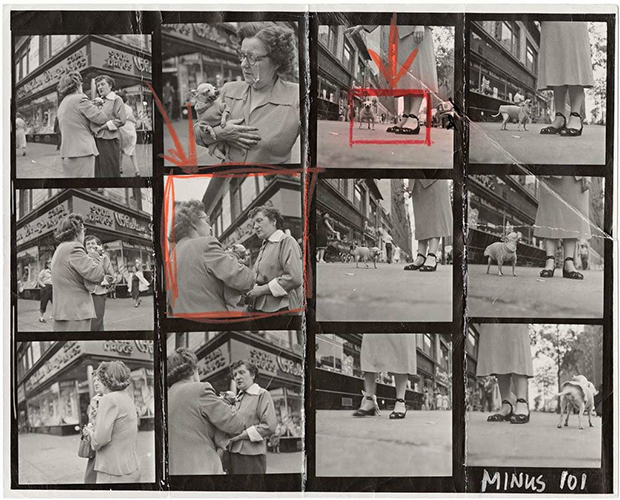

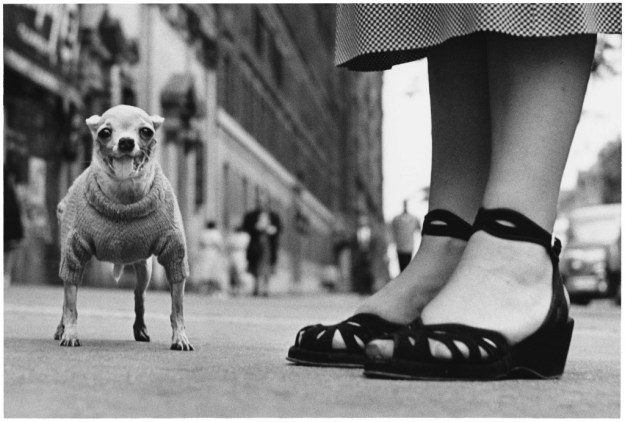

The second of the photographers is Eikoh Hosoe, an influential Japanese artist known for his experimental art using photography and motion picture film. Although a prolific curator of photo-books, his most famous work was during the 1960s, when he collaborated with an emerging form of interpretive dance called Butoh. This form of dance rebelled against convention in that its slow, almost tortured movements created imagery that could be considered macabre, evil or taboo. Even today, Butoh is considered a dance that cannot easily be qualified or categorised, but at that time it was considered to be a form of subversion. Hosoe began working with the founders of Butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno. Hosoe believed that photography didn’t have to be expressed simply by taking pictures of a subject, instead he wanted to create a counter-realism in his work. He described his desire to create, rather than document in a video interview with The Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2011 [4], saying that photographers of the time believed his use of the camera to not be photography. His work with Hijikata produced a series called Kamaitachi (the weasel’s slash), an ancient Japanese legend about a demonic creature that attacked people with blade-like limbs, metering out some form of evil recompense on those who sinned. The legend encompassed everyone, from children to adults and was most feared in the rural prefectures of Japan throughout its history. In his work, Hosoe combined the imagery of Hijikata’s birth village with his dance to create an aesthetic of historical consistency (the legend) against a backdrop of a rapidly-changing Japan. A photograph from the series can be seen below.

From Kamaitachi, 1969 by Eikoh Hosoe [5]

Here we have Hijikata mid-leap in front of a small group of children, set against a barn-like building in what is quite clearly rural Japan. The composition itself is fairly conventional with the dancer on the righthand third of the frame and the children in the central lower third. What is interesting about this picture is the way the natural reactions of the children support the external context of the collection. Their surprise at the feat of flight and fear of where he might land, lend themselves to the legend of the flying demon who may swoop down on any one of them. A little girl puts her hand on her friend’s head as if to protect her from the demon who’s outstretched arms resemble the claws of the creature and flowing clothing its wings. Even without the external context information, the image is disturbing because of our in-built belief that it’s not right to frighten children. Hosoe creates the imagery in an environment that would be considered safe to the children; their way of life captured in a semi-documentary fashion. When looking at the

Kamaitachi series, Hosoe’s use of convention to create rather than capture is very clear.

Kamaitachi is unconventional portraiture in the same way as Woodman’s work with the subject being the focus but not the only element that needs to be viewed. Hosoe also shot portraiture as it’s more widely known, most notably his early series Ordeal by Roses, in 1961, featuring a well known writer called Yukio Mishima. In this series, Mishima appears in high contrast black and white in surreal poses, often nude but erotic rather than overtly sexual. The rose is portrayed as both beautiful in its foliage but with the hidden dark side of its thorns which is both striking as a visual aesthetic but also gives an impression of how the photographer had grown to see Mishima. Consider the photograph below from this series.

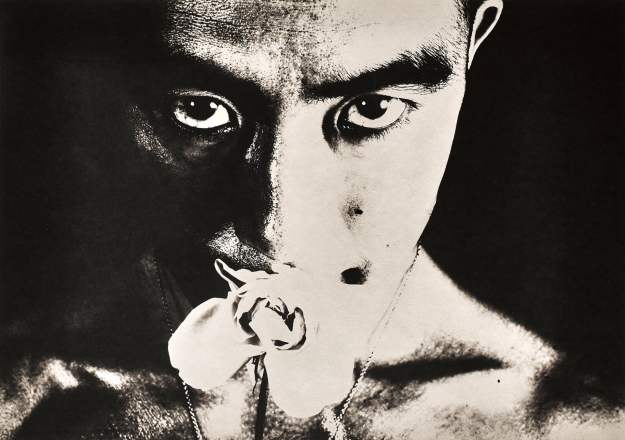

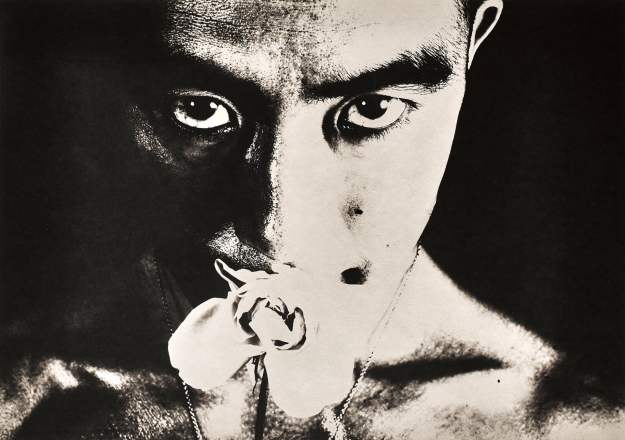

Ordeal by Roses #32, 1961 by Eikoh Hosoe [6]

Here we see a direct portrait of Mishima staring straight into the camera. The lighting is harsh and the contrast has the effect of emphasising the intensity of his stare. It also reduces the detail of the rose in his mouth to just enough to preserve its beauty. When I look at this image, I see the conflict in Mishimi’s face. His expression is almost seductive because of the rose, but we can also interpret a level of pain or sadness in his eyes. Perhaps the thorns of the rose are physically painful and that its placement is almost silencing this famous writer (Mishimi was later a right-wing nationalist who led an unsuccessful coup to restore power to the Japanese Emperor). It could be instead that the sadness is of desperation and that the rose represents the need to be loved. It’s a powerful image that, when included in the rest of the series, highlights the experimental nature of Hosoe. When I look at this image, I see something more akin to a painting than a photograph, because of Hosoe using his camera to create rather than document.

Nan Goldin 1953 to present day

Nan Goldin is a photographer than I was well aware of before I started this course and I must confess to not being a fan of hers. Most of the images that I had seen at that point just didn’t interest me as my aim was to improve my understanding of photography as a technical discipline. Goldin’s work by contrast appeared to contradict my understanding of a good photograph, with the heavy use of flash, soft focus and unconventional composition. Reflecting on my progression throughout this course, I chose Goldin as the third photographer to research as part of this post to see if anything had changed.

The starting point for my examination of Goldin began with the documentary that I referred to in my response to my tutor’s feedback on Assignment 5 [7]. During the conversation, she referred to the way that people look at things now vs. before social media. In her work, the first thing that strikes me is the way she has seen the moment or the connection she wanted to capture in her pictures. During her time living in the transsexual community in New York in the 1970s, Goldin photographed the people that she spent time with and often lived with. By photographing the people that she formed strong friendships with, Goldin was able to capture them affectionately, in private and social situations where they were simply being themselves. Her intent to photograph only who she loves was discussed in an interview with Tate [8] where Goldin says that she could never photograph people who were ugly or disturbing to her and never out of anger; her photography was born out of love for her subjects. In her early work in the 1970s, Goldin celebrates her friends at a time where transgender people faced discrimination and prejudice in their daily lives, but continued to chronicle their struggle as the AIDS epidemic terrifyingly spread through their community. Her photographs eventually became a book called The Other Side, which was published 20 years later, which has been interpreted as a reminder of the impact of the disease on what was considered a minority society. However Goldin contests this in her intent behind the work The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, perhaps her most famous work that began as a slide show and was then turned into a book. Goldin described the stories of people in their relationships across genders, stating that her circle of friends simply didn’t care about what other people considered normal [8]. Her pictures captured their lives as they unfolded, seeking to tell their story honestly, as opposed to some creative revisionism after the fact. In addition to her friends, Goldin included a documentary of her own troubled love-life where she was subjected to domestic violence.

Nan one month after being battered 1984 by Nan Goldin [9]

In the above self-portrait, Goldin appears heavily bruised by an act of great violence as a long-term and volatile relationship had broken down. Of the image, she wrote

‘I took this picture so that I would never go back to him.’ [9]

Goldin’s photograph is starkly lit to emphasise the damage done and composed against an ordinary, almost dull background. The onboard flash rolls off in a vignette which creates a sense of loneliness and sadness, but the brightness of her lipstick points to someone who has just recognised that she has to move on. The injury was so severe that she nearly lost the sight in her left eye, which can be read on her expression in this image. I am left wondering if she thought that blindness was inevitable now that she had effectively opened her eyes to her situation. In almost every case, Goldin’s pictures have an ‘instant’ quality about them, which is not really a surprise when her first camera was a Polaroid that she was given in the late 60s. She later stated that she used whatever camera came into her possession [8], taking no interest in the gear, but rather the subject. Her compositions too suggest little in terms of preparation, capturing fleeting moments of every emotion, good and bad often using harsh flash lighting (she claimed to not understand the effect of light on colour until the late 1980s). For me. this belies the skill in creating the image, each one containing everything needed to create a narrative in the viewer, some that engender warmth and some disgust or horror.

In her more recent work, Goldin has focused more on children than adults but remains personally connected with her subjects. While her style hasn’t deviated much from her original work, Goldin’s fascination with the creative freedom and undefined beauty of children comes through in softer, more varied images than before. She states that by paying attention to the way children interact with the world, she began to believe that they were from a different planet. A shot from her collection Eden and After can be seen below:

Ava twirling, NYC, 2007, by Nan Goldin [10]

Here we see a young girl in a flowing dance with another child in the background who appears to be doing something similar. Goldin has captured the movement of the little girl as she twirls her dress. The joy in her expression suggests that making shapes with her clothing is something of a new experience and she enjoys showing off her new-found form of play. What strikes me about the composition apart from the movement is the softness of the light. Although likely to be artificial, this image departs from the stark on-axis flash look and suggests calm, relaxation. The background details of the bedroom create a cosy, family environment where children can be themselves. Goldin’s book seeks to be a tribute to children but also something that belongs to them [10] as opposed to the adults that they will ultimately become. In the interview with Tate, Goldin talks about how the children she photographed decided upon their movement, costume etc without any direction from her. This lack of adult ‘interference’ creates an aesthetic of playful freedom throughout the work, which Goldin captures beautifully.

Watching her interviews and reading her perspectives on life and art, I’ve moved away from my initial impressions of Goldin. Her approach to art through the medium of photography is refreshing. Unlike me, her interest has only ever been how she expresses her view of the world and creates an honest narrative of her life and that of her friends. Her style is unquestionably experimental and to be honest, many of her photographs leave me cold because of how they are shot. However, even those give a sense of ‘that’s ok, just look at what I’m looking at, feel what I am feeling’.

Edvard Munch 1863 to 1944

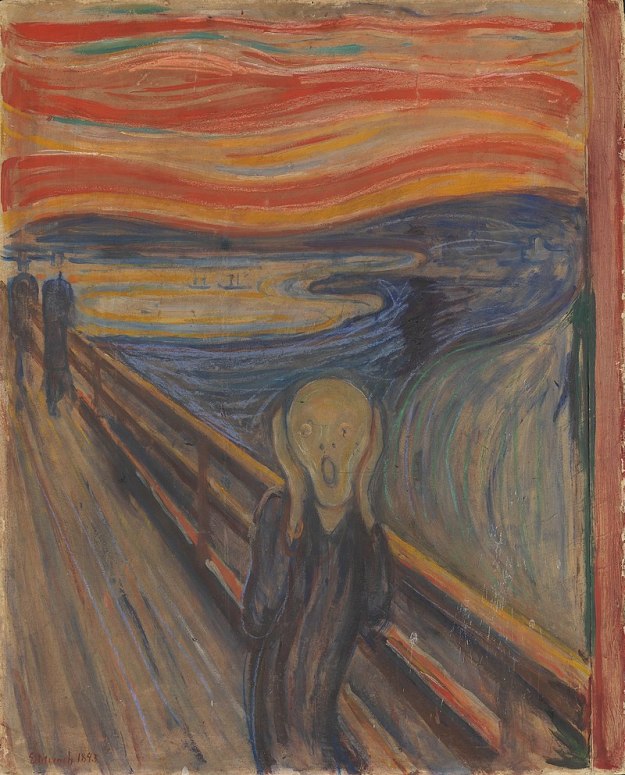

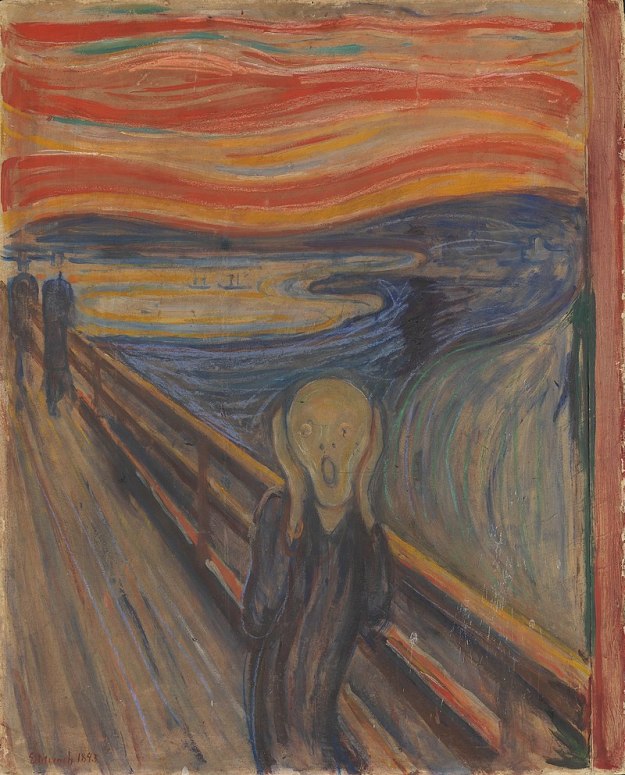

The first of the portrait painters I looked at was Edvard Munch. The Norwegian painter is, of course famous for his iconic painting The Scream, which he produced in 1893 and which depicts a figure in anguish at sunset by a stretch of water. When researching The Scream, a number of little known elements point to other parts of Munch’s artistic style and personality so my interested started with that painting.

The Scream, 1893 version by Edvard Munch [11]

Munch described the circumstances that inspired this painting as a walk with friends at sunset. As he turned to look at his friends, the sky turned a blood red, which engulfed the scene. He commented

“I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature” [12]

So intense was that feeling of anxiety, contrasted with the apparent dismissal by his companions, Munch painted the figure in distress at the scream of nature. He further strenghens the horror of the moment by making the figure largely featureless but androgynous, resembling our modern representations of the extra-terrestrial. Munch was a painter the worked with his memory or feeling about a situation rather than a specific subject. While we know that painted portraits lend themselves to large degrees of artistic licence, Munch’s work (including the scream) dispenses with precise detail and deals almost exclusively with his own emotions, that could be completely unrelated to the subject he is working with.

Munch’s life was undobutedly tragic, losing both his mother and older sister to tuberculosis, his own health issues including a descent into alcoholism and having a highly destructive relationship that we could judge as abusive by today’s standards. It seems fair, then that Munch had a great deal of torturous feeling that drove his work. He said

“My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder….My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art.” [13]

Munch’s relationship with Tulla Larsen, which he found himself pressured into, created many works in which he painted himself as a sufferer. His paintings ‘capture’ a mood rather than document an event. In some cases, he painted classical stories and put himself and Larsen in them. For example The Death of Marat, 1907 in which the French Revolution general Marat is assassinated by Charlotte Corday [13] Much casts himself as the victim and Larsen as the killer, emphasising her seductiveness by making her a nude figure. In another self-portrait during a seemingly ‘settled’ period in their relationship, Munch paints himself and Larsen in a pose that is far from a traditional love story. After their relationship broke down, Munch sawed the painting in half to spite Larsen; the effect being similar to a modern-day break up where people are torn out of photographs.

Edvard Munch, “Self-Portrait with Tulla Larsen,” ca. 1905 [14]

When we look at this painting, we see an angry Munch glaring at a dispassionate Larsen while a figure looks on in the background. Munch’s use of contrasting colours of red and green brings the couple out of their situation and puts their argument front and centre for the viewer. The character behind them has an equally stern expression as if in disapproval of their behaviour. Or perhaps the reds mean something else and Munch’s expression is more of passionate love than anger. The figure behind could equally be another admirer who is unable to get close in the way that Munch does. The flame haired Larsen appears distant or disengaged, which could be because of Munch’s reluctance to marry her, something she hounded him for during their relationship. Theirs was certainly a firey match that ended in Munch losing part of a thumb in an incident with a pistol.

I greatly admire the way that Munch created imagery of pure feeling rather than of events or the reality of what he saw. It’s no surprise that The Scream provokes such a reaction when viewed as it creates a mood of fear and shock that we can relate to in the modern world.

Alberto Giacometti 1901 to 1966

The final artist I looked at for this post was the sculptor Alberto Giacometti, who I only really learned about recently during the BBC’s Fake or Fortune television programme. A work alleged to be by him was being examined for authenticity and was eventually proven to be genuine through establishing providence. What I first noticed about his work was the surreal nature of his sculpture, in particular when he created pieces of ‘portraiture’. In my research into Giacometti, I discovered that although he was known as a sculptor, like many artists he also painted and sketched. What’s more interesting is that his work in each of these media, the recurring technique of how he represented people can be seen, Consider one of his early sculptures Woman with her Throat Cut, 1932 [15]

Woman with Her Throat Cut, 1932 by Alberto Giacometti [15]

Here we have a surreal representation of a violent rape and murder of a woman. At first glance, the figure looks like an insect that has been squashed, but when we look closely, we see the long elegant torso of a woman with large breasts and long limbs. Giacometti has posed the figure with legs splayed, suggesting sexual activity and twisted the arms to suggest a collapsed figure. The elements of the sculpture that point to death and violence are those that are emphasised by Giacometti out of proportion and not in the least bit anatomically accurately. Her open rib cage sits attached to her right leg and an pelvis-like object pins down her left arm. Her right arm is weighed down by a phallic shape, which when combined with the other elements and the pose, suggest rape. The woman’s neck has been extruded into a long arterial object which clearly has a cut across it and her head is incredible small. In drawing attention to some areas more than others, Giacometti tells the story without the subject being seen as a human being. In the same way that Woodman and Hosoe used their subjects to create a narrative without worrying about realism, Giacometti’s sculpture is very unsettling, once the viewer sees the elements being brought to their attention.

The way that he expresses people is evident in his other sculpture, with women being portrayed as tall, elegant creatures with long necks. They are posed in an almost fragile way with the recurring theme of heads being much smaller than their bodies. Perhaps Giacometti is describing the beauty of the female form without worrying about the features of the faces, which are characteristically devoid of any real detail. What I didn’t realise about Giacometti was his ‘process’ of creating art and how these forms took their peculiar shapes. In the Artists Muse sale of works by Christies in 2015, a video [16] was made to tell the tale of how Giacometti painted his famous portrait of James Lord. Lord was a well known author and biographer who wrote his own book about the painting that took nearly 3 weeks to ‘complete’. I say ‘complete’, because the painting is seen as nearly finished as can be seen below.

Portrait of James Lord, 1964 by Alberto Giacometti [16]

The video describes the sitting in Lord’s own words. Giacometti started by creating a figure with an elongated head. His emphasis of the head with its long neck was a surprise to Lord as it lacked any real structure with respect to the vague body it sat on. The background started out as pretty much a blank area with only a few details to define space around the subject. As the shoot went on, Lord observed Giacometti’s continued doubt about how the work was progressing, stating at every stage that he wanted to start again from scratch. He didn’t, of course but Giacometti was not using any preconception of what Lord should look like, nor was he mentally relying on what he had painted previously. This preparedness for scrapping the painting at any time and beginning again, kept Giacometti’s creativity working. Lord also observed the artist’s melancholic self-doubt that the painting would ever be any good and the fact that at times, Giacometti would abandon the painting and the sitting at no notice to go to his favourite bars in Paris. Every time he came back to the painting, Lord observed that it improved dramatically with the final image being the best it could be.

In Conclusion

I conducted this further research in response to the feedback on Assignment 5, which I felt was a justifiable observation that I only looked at photographers or artists that I already had an admiration for. The artists that I have looked at here are all very different, but they have one thing in common. Each has a central reason for being an artist, whether it is to express how they feel, rail against conventional realism or to document something they care about deeply. I was taken with Woodman’s introduction of movement and the use of her body as something different from a conventional naked woman. I admired the fun but dark subjects that she shot and have realised that some contextual influences, such as her tragic suicide can steer us to a single analysis of her work. The same can be said of Goldin’s very candid portraiture of her friends, many of which have died through AIDS or addiction. I was never really a fan of Goldin’s work because of the initial impression of a snapshot rather than a considered capture of an important moment. I now see her work as an affectionate presentation of her life and the ups and downs of her relationships with the people she loved. I find her work with children to be uplifting in a way that we don’t see in the modern world. Goldin herself said that the believe the world was a horrible, but that she saw light in children.

The photographer that I have developed an admiration most of all is Eikoh Hosoe. His decision to protest against the realism of photography while preserving the culture of his native Japan was fascinating to me. His desire to use photography to create something surreal was echoed in the work of Munch, who only painted what he recalled or felt about a subject. He shared similar anxiety and self doubt that Giacometti suffered from, which comes though in the work of both artists. What I have taken from this piece of work is some ideas of how to free my creativity from the overwhelming desire to produce technically good photographs. Developing my own voice doesn’t have to depend on being strange or surreal, but it does need to be about what is important to me and it does need the viewer to really look at what I might be trying to say.

References

[1] Wrigley, T, 2018, “How Photographer Francesca Woodman Came Into Her Own in Italy”, AnOther.com, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/11170/how-photographer-francesca-woodman-came-into-her-own-in-italy

[2] McWilliams, J, 2017, “Ideas and a New Hat”, Paris Review, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/01/19/ideas-and-a-new-hat/

[3] Cooke R, 2014, “Searching for the real Francesca Woodman”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/31/searching-for-the-real-francesca-woodman

[4] Art Gallery of NSW, 2011, “Photographer Eikoh Hosoe on his work and inspirations”, YouTube Video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xgk98N8N9Ro

[5] Hosoe, E, 1969,”Kamaitachi, Photographs by Eikoh Hosoe”

[6] From “Ordeal by Roses”, Image Resource, http://www.michaelhoppengallery.com, https://www.michaelhoppengallery.com/artists/89-eikoh-hosoe/overview/#/artworks/11361

[7] Fletcher, R, 2019, “Feedback on Assignment 5”, blog post

[8] Reeves, E, 2017, “On the Ballad of Sexual Dependency”, MOCA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iDSvD0yhjWQ

[9], Goldin, N, 1986, “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency”, Aperture

[10], Tateshots, 2014, “Nan Goldin – My Work Comes from Empathy and Love”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_rVyt-ojpY

[11] Image Resource, “The Scream,”, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Scream

[12] Phaidon, 2012, “Edvard Munch’s The Scream: a few facts and theories”, https://uk.phaidon.com/agenda/art/articles/2012/may/02/edvard-munchs-the-scream-a-few-facts-and-theories/

[13] Lubow, A, 2006, “Edvard Munch – Beyond The Scream” The Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/edvard-munch-beyond-the-scream-111810150/

[14] Solly, M, 2019, “British Museum Reunites Portrait That Edvard Munch Sawed in Half to Avenge His Fiancée”, The Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/british-museum-reunites-portrait-edvard-munch-sawed-in-half-avenge-fiancee-180971936/

[15] Flint, L, 2018, “Woman with her Throat Cut”. The Guggenheim Museum, https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/1424

[16] Christies, 2015, “Alberto Giacometti’s Portrait of James Lord”, Video Article, https://www.christies.com/features/Alberto-Giacomettis-Portrait-of-James-Lord-6658-3.aspx