Introduction

The natural world provides us with a huge and complex light source that varies with the time of day, the weather and the season. It interacts with our subject in an even broader range of ways, which we can manipulate to achieve the photographs we want. However, the visual impact of light we create artificially goes somewhat unnoticed by many. This kind of light is created to draw attention to a subject such as an advertising poster or to allow us to see where there is no natural illumination. As with the early days of photography and the evolution of flash light sources, artificial light was a tool to be used to capture the image on film rather than be something that could independently considered beautiful.

Creative Control

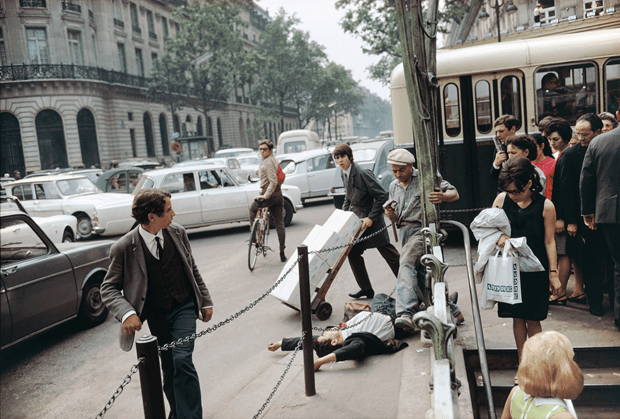

The first idea we are introduced to in this project is the use of light in motion picture film, the example being In the Mood for Love by Wong Kar-Wai. This movie depicts a love story between two people who’ve discovered that their partners are being unfaithful with each other and how their own fantasy affair develops. The film is shot predominantly at night and the lighting used creates the sense of clandestine activity in between the highlights and shadows. The dismal nature of their environment is contrasted by the lighting of the female character, Su’s colourful clothing and throughout the film, the angles used by the cameraman further emphasise the voyeristic aesthetic that the street lamps and lightbulbs reveal to the viewer. When I saw this film, I was struck by the simple way that fluorescent lights used cast colour on the character’s skin that one would expect to be harsh in its unrealistic luminance. However, the way that the faces of the characters are picked out draws attention to their mood in a way that almost makes the colour cast unnoticeable. One frame from the film is discussed by Ian Bryce Jones on his blog:

From ‘In the Mood for Love”, Wong Kai-War [1]

Everything about this shot is utterly stunning. The light on Su’s face is perhaps the most dramatic in the entire film: bright, sharp, highlighting the shadows under her cheekbones and her winged eyeliner, and also very artificially coloured, almost golden, making her lipstick look brighter and her features more defined. Chow is behind her, in a different depth of field; still, we can tell that his gaze is on her, and the resultant tension is incredible. – Ian Bryce Jones, 2015 [1]

What interested me about this shot was the control used by the cinematographer, Christopher Doyle. The whole film was shot on Kodak Vision 500T and 800T colour negative film [2] which is about as good as it gets for truly representing colours in artificial light (T is for tungsten balanced) It’s most common use is for indoor shots where fluorescent lighting would normally create a colour cast like the one in the photograph above. Therefore in order to create this effect on Su’s face, Doyle had to use a light that would overcome the effect of the tungsten balance reaction of the film emulsion. As Ian Bryce Jones states, the use of this golden light emphasises not only the expression of her face in terms of highlight and shadow, but the cast brings out the boldness of her lipstick. The male character behind her is lit by the spill from the key lighting, which when coupled with his being out of focus, offers minimal information beyond the fact that he is looking intently at her. It is a remarkable frame from an impressive film.

Colour balance in modern terms

As mentioned, the film stock used in that film is biased towards rendering natural colours from artificial light. It is designed to represent colours in light of a certain colour temperature and cannot be physically changed outside of using additional filters on the camera. Colour temperature refers to a measurement of the electromagnetic radiation that makes up the visible light region and varies depending one the light source. The scale of colour temperature (in degrees Kelvin) runs broadly as follows:

With digital cameras, balancing for colour temperature (referred to as white balance), is something we have control over as opposed to choosing a film to cope with one scenario. If the camera is set to automatically assess the light in the scene, it will correct for the dominant colour temperature. Many photographers will work this way and correct in post processing, which is most effective when shooting in the RAW format. As we can see from the frame from the movie though, careful selection of colour balance is important in creating the aesthetic using artificial light. If, for example we import the image into photoshop and autocorrect for the dominant light source, we get the image below. The skin may be more ‘representative, but the whole feel of the image is now changed and in my view, worse for it.

Colour corrected version of the previous image.

The Photographers

The three photographers mentioned in the course notes all use the impact of artificial light that is present at night on the streets. Shintaro’s work in the bright metropolis of Tokyo, deals with the varied and impactful way that light is used to get the attention of the people, whether it be informational or as advertising. The landscapes are dominated by strong lighting but with contrasting colours that spill into the shadow regions and reveal hidden textures. Shintaro’s images are largely free of people, which the artist ensures by using long exposures. When people walked into his frame, he would temporarily cover the lens and wait for them to move on, which meant that although the exposure was a total of 30 seconds, a single shot might take 30 minutes to produce.

“I wanted to show the thing itself. If people show up in the frame, the viewer sees people. Just the signs, just light, just colors, just the thing itself. And the rhythm these things were making.” – Sato Shintaro, 2009 [3]

Shintaro’s photographs empty the scene of distractions, yet the subjects still point to a pattern or even struggle of life.

Tokyo Twilight Zone, 2008, Sato Shintaro [4]

In the photograph above, from his series Twilight Zone we have a mix of the light pollution from the city at the horizon with the light from the houses in the foreground. The combination powerfully shows thousands of people living their lives without a single person being in the image. The statement of Tokyo confronting the night with lots of its own light is enough to be an interesting subject, but the beauty of the light graduating from cool tones of the foreground to the warmer skyline makes it a photograph to linger on.

A consequence of long exposure that makes Shintaro’s work so powerful is what cannot be seen by the human eye or appreciated by the bran in real time, something I have experienced during night photography shoots. As I’ve mentioned previously [5], the human eye and brain are continuously adjusting ‘exposure’ so that we have consistency of vision. Where there is a high dynamic range of light, we often miss the subtlety of the low lit areas of a scene because of the way we process what the eye sees. In the case of a slow changing scene with very low light dynamic range, we can see things that we would ordinarily miss; consider the mariners who see iridescent algae when at sea when there is little light pollution from other sources. With long exposures, we can see reflections and subdues shadow tones that our brains tune out in the presence of a dominant light source. Take the image below for example:

St Paul’s Cathedral, 2017, by Richard Fletcher

This shot was taken on a rooftop in London on a very stormy night. When I set the shot up originally I had observed the way St Paul’s was reflected in the water, but I hadn’t spotted the lighting of the cloud above the dome. By exposing for longer, this effect became more obvious.

London – A Modern Project, Rut Blees, 1995

With Rut Blees Luxemburg’s’ famous image used on the cover of The Street’s debut album, we have a similar feel to Shintaro. This time, the gloomy London sky is punctuated by yellow street and building lights. What is interesting here is her observation of light that is similar being altered by the people producing it. The building has a mixture of different curtains and window coverings that alter the intensity and colour, drawing the eye around the subject and revealing textures that would ordinarily be missed. By using a long exposure, the dynamics of the lives of the people who live there are also captured via the lights from their apartments. As with Kar-Wai’s film, the general darkness of the frame and the incandescent lighting create the urban effect that appealed to the musicians that used the image. The image was originally part of the collection London – A Modern Project, 1995 where the theme uses the same lighting ideas throughout.

I think the sculptural quality of the block is what makes the picture work. The lights break up the grid, but at the same time they are little illuminations, which tell us about the people who live there. While the camera shutter was open, people came home and turned their lights on or off. The brightest rooms either had their lights on for the longest, or they had stronger lights. And in some, you can see people watching television. In that sense, the picture is a living sculpture. – Rut Blees, talking to The Guardian in 2009 [6]

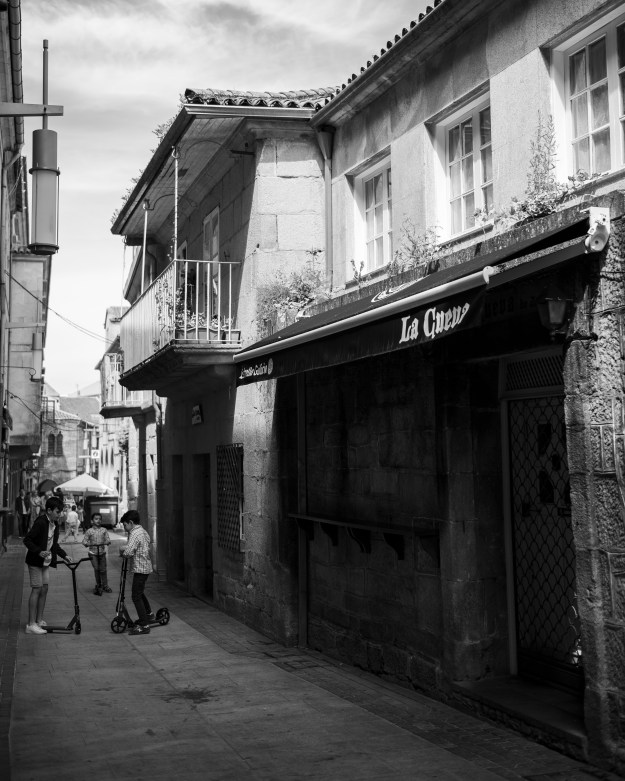

The final photographer mentioned in the course notes was Brassaï, who worked in the early part of the 20th Century. His work in Paris in the early 1930s observed the way that simple street lighting interacting with the environment and weather to create surreal views of the famous city. What differs with Brassaï’s work from the others researched here is the more traditional approach of showing people in their environment. He used high contrast imagery to reveal the contrast of Paris itself, ranging from the glitz and glamour of the Eiffel Tower to the depression of homelessness in the deprived areas of the city. He worked in black and white film, which was the only practical medium available to him, resulting in a large grain effect under low light conditions, further enhancing the gritty nature of his images.

“The surreal effect of my pictures was nothing more than reality made fantastic through a particular vision. All I wanted to express was reality, for nothing is more surreal” – Brassai, on the publishing of Paris de Nuit, 1933

In his interview with Tony Ray-Jones in 1970, Brassaï discusses the origins of his work which drew on his early days as a painter and were inspired by, among others Georges de la Tour, a 17th Century French painter. La Tour’s paintings of subjects lit simply by candlelight, were not unlike other painters of the time. However, like Rembrandt, who was 13 years his junior, La Tour carefully used the single candlelight source to draw the eye to the main subject and let the viewer explore the the areas where highlight descends into shadow. One can see the influence of the painters in some of Brassaï’s ‘portraiture’ that makes up his collection Paris de Nuit. An example can be seen below. The primary light source reveals the vendor and just enough of the setting around him for the viewer to see his profession. His expression is one of concentration but not awareness of his surroundings or the fact that he is being photographed. It is also a good example of Brassaï’s honesty in his photographs, where the image retains large areas of dark shadow that many would have considered cropping out. Brassaï believed that photographs should have order and that the composition should represent the subject faithfully, particularly when photographing people [7].

Kiosque à Journaux, Paris 1930-32 by Brassaï

Conclusions

This project has led me to re-evaluate artificial light, which until now has mainly been the use of strobes in portraiture. While I’ve always appreciated how this kind of light affects the subject and its setting, particularly when combined with long exposure techniques, I have yet to explore the quality of the light itself. Of the creative uses of artificial light examined here, the most interesting to me from an aesthetic point of view is the cinematography on the film “In the Mood for Love”. Here, seemingly ordinary tungsten lighting creates a beautiful, secretive, but painful mood throughout the film. It has made me see all sources of light from a different perspective.

References

[1] Bryce-Jones, I, 2015, “Silhouettes, Shadows & Smoke: Lighting in In the Mood for Love”, https://intermittentmechanism.blog/2015/06/10/silhouettes-shadows-smoke-lighting-in-in-the-mood-for-love, accessed June 2019

[2] Unknown Author, 2012 -2019, “In the Mood for Love (2000) Technical Specifications, https://shotonwhat.com/in-the-mood-for-love-2000

[3] Kurt, 2009, “Interview with Sato Shintaro”, http://www.japanexposures.com/2009/08/25/interview-with-shintaro-sato/

[4] Dirk, 2008, “Sato Shintaro – Twilight Zone”, http://www.japanexposures.com/2008/09/24/sato-shintaro-twilight-zone/

[5] Fletcher, R, 2019, “Light Meters” https://wordpress.com/post/richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/876

[6] Benedictus, L, 2009, “Photographer Rut Blees Luxemburg’s Best Shot”, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/apr/23/rut-blees-luxemburg-best-shot-photography

[7] Ray-Jones, T, 1970, “Tony Ray-Jones Interviews Brassaï, http://www.americansuburbx.com/2011/08/interview-brassai-with-tony-ray-jones.html