Approach this exercise with care and a diligent awareness of health and safety both for yourself and others.

Closely consider the work of the practitioners discussed above, then try to shoot a series of five portraits of subjects who are unaware of the fact they are being photographed. As you’ve seen, there are many ways in which you can go about this, but we can’t stress enough that the objective here is not to offend your subjects or deliberately invade anyone’s privacy. If you don’t have permission to shoot in a privately-owned space, then you should only attempt this work in a public space, where permission to shoot is not necessarily required.

This is a very interesting challenge, which some students will find incredibly difficult. Remember that the creative outcome of the practitioners discussed above has come about through a sustained approach, which is then heavily edited for presentation. You’ll need to shoot many images in order to be able to present five final images that work together as a set.

Think everything through carefully before attempting this exercise as the responsibility for the outcome of the portraits rests entirely with you. If during the course of this exercise you are challenged in any way, be prepared to delete what you have shot. If you can see that you are annoying someone, or making them feel uncomfortable, stop shooting immediately. You’ll be required to operate with a degree of common sense here and not take unnecessary risks. There are ways of completing this exercise without incurring risk, such as shooting the work at a party you’ve been invited to, where all the guests have been invited for a particular celebration.

The reflection about your methodology (your approach to how you have achieved the images in relation to why you chose what you have chosen), will be as important as the final five images, so be prepared to write about how you found the experience (around 500 words) and present your findings via your learning log or blog.

Introduction

I started thinking about this exercise shortly after researching Walker Evans’ series Subways. His work was pioneering in capturing people off guard, but for me the way that it really works is the fact that they are completely unaware of the photographer working. What sets him out from the other practitioners in Part 2 is this stealthy approach. With Parr’s similar series, I suspect that his subjects were not entirely unaware they were being photographed in some cases. As discussed in Project 1 [1], I base this suspicion on the way that Parr shoots, close-up with flash. If the subjects were asleep, they would not be aware, but they could similarly be defensively trying to hide their faces. Japanese culture is one of deferential privacy, particularly on public transport which led me to conclude that some would just be hiding their gaze from Parr. diCorcia’s Heads series has the aesthetic of people being caught unaware through his use of a camera trap. However, diCorcia freely admits that he made himself visible throughout shooting and that people could see what he was doing[2]. They were certainly aware of being photographed as soon as the flash went off. With Tom Wood’s series Looking for Love, again the subjects were aware of his prescence but had gotten so used to him that he effectively became invisible. When Meyerowitz walked the streets of New York with his Leica, he shot people from very close up and in their sightline. Meyerowitz stated that people just didn’t believe that he was interested in them [3]. For me, the only practitioner that achieved complete anonymity was Evans, although people clearly found his attention to be suspicious – they weren’t aware of what he was actually doing.

For this exercise, I was inspired by Evans’ hidden camera. Instead of looking at people, I decided to shoot people who were behind me and outside of my sightline. I wanted to capture people moving behind me, queueing for something or just going about their business completely unaware of my presence. For me, this would be shooting the very unaware, with the added complexity of my also being unaware of the exact composition as the pictures were being made.

The Setup

I thought about which camera to use from my collection and actually determined that my phone would be most suited because of its high resolution, wide angle lens and silent shutter. It also had a sophisticated automatic focus and exposure system that would avoid the need to pre-setting as Evans had do in the 1930s. The phone also had a remote shutter release in the form of its cable headphones, which meant that I could very discreetly take the picture through the seemingly unconnected gesture of adjusting the volume control. The next consideration was how to get the camera to face backwards, which I solved by installing my phone in a modified backpack. Although tricky to fabricate, I managed to get an aperture that the phone camera could view though and disguised in a way that it was hidden from my subjects. The completed rig is shown below:

The images show the makeshift phone holder, remote extension cable for the headphones to connect to and the apertures at the back of the backpack. The left hand aperture was aligned with the camera and the right hand one was a dummy. The badges were added to distract from the apertures themselves.

The rig was challenging to use because of the fact that I could position myself in what felt right relative to the subject but there was always the risk of it being completely off in terms of composition. Even if I was aligned properly, the angle of the backpack to the subject made for some interesting horizons. I also had problems with the phone itself – the cable kept coming out of the socket on the bottom, which meant that I missed many shots that I thought had worked.

The Images

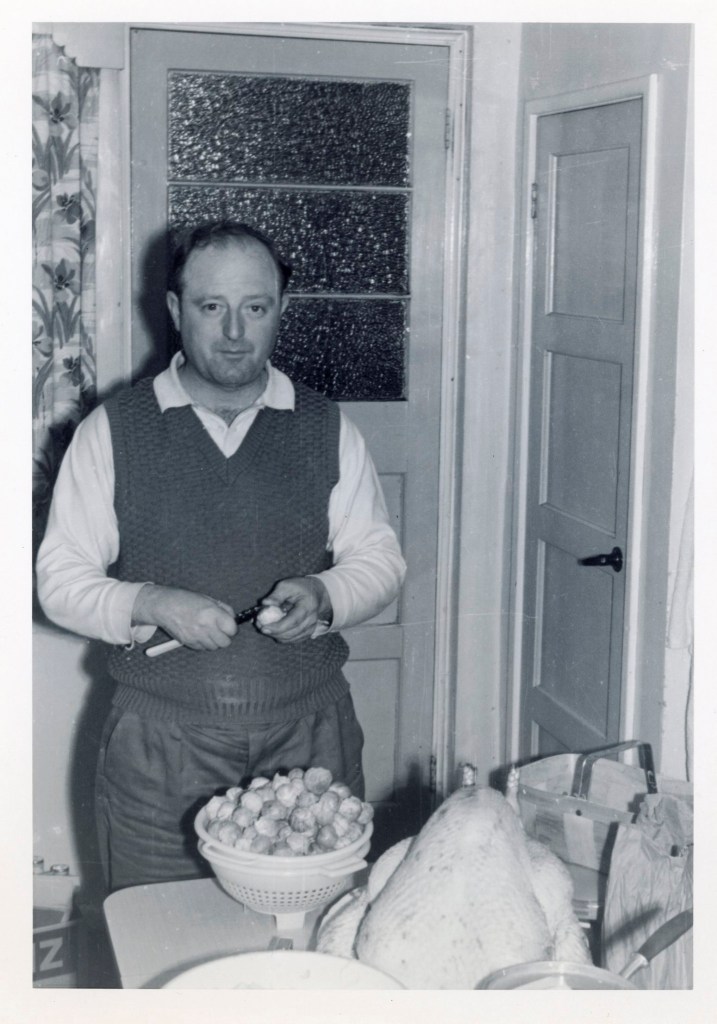

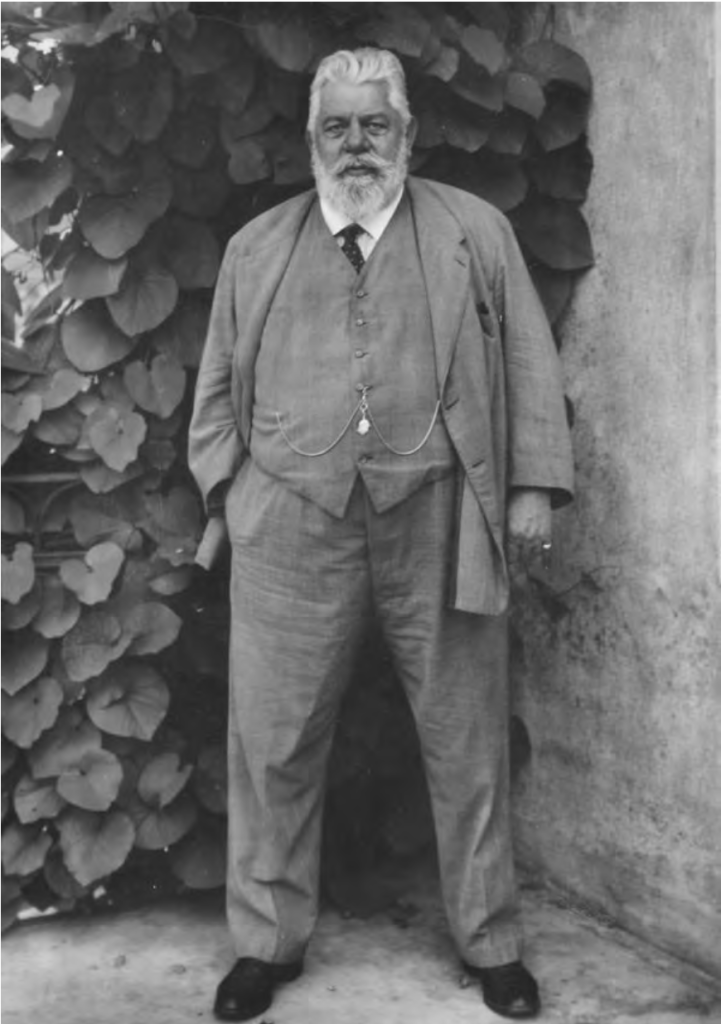

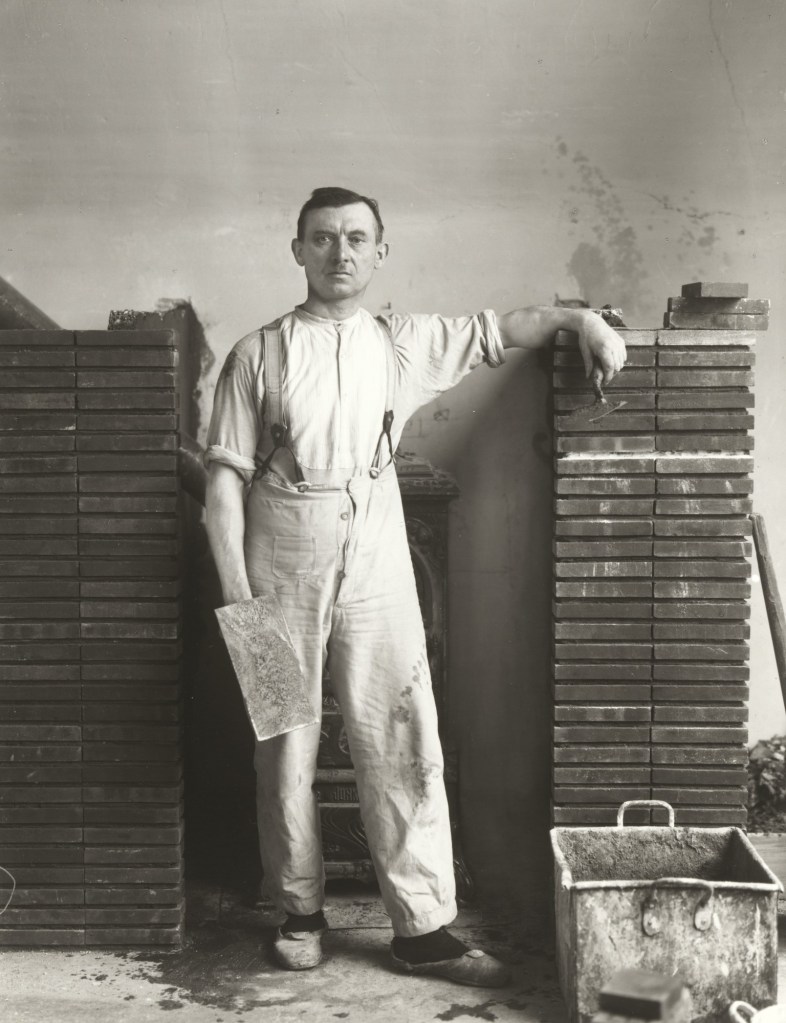

When I reviewed the images that I did get, I was interested to observe how people interact with their environment and each other when they are not obviously observed. To add to my deception, I carried one of my old film cameras (without any film) so that I could pretend to be photographing in the opposite direction to the backpack. In shot One, one of the subjects can be seen looking in my direction – I assume it was the sight of the old camera that drew his attention. It was this sneaky look, coupled with my own subterfuge that led me to make the series about being ‘going unnoticed’

Reflection

In this series, we have a mix of subjects with some single, some couples and a group shot. One each photograph, the subjects are going about their lives completely naturally without any idea that they are being photographed. To that extent, I think the photographs work in terms of The Unaware. As a series, the only anchor is the fact that they are all shot outside in my home town. Unlike Evans’ different subjects in a common environment, my series uses this anchor as well as the fact that they are all unobserved. With Evans’ series, the viewer is challenged to question what the subjects are talking or thinking about. In my series, the questions are more broad, e.g. in Two, the gentleman appears to be strolling through he park with a thoughtful expression on his face, where in Three there is a lively conversation taking place. What is the lone man thinking about as he walks and what are the two people talking about that creates such a lively expression through their gestures? I showed the series to a friend of mine when complete and he immediately pointed out that “he’d seen that person or those people before”. When I reflect on the series, I too see people that I recognise, not because I know them, but because of how familiar their activities are. The family walking through the park is typical of most families I encounter when I spend time there, often with 3 generations out enjoying each other’s company. The climate protestor is a regular sight in town as she sits motionless and disengaged from the people around her. Her demeanour clearly shows her determination to speak for the planet, not its people. Most of Malvern’s residents just walk past her and at first, I wanted to represent her apparent invisibility. However, where she now sits makes it easy to completely avoid walking past her, so there were no opportunities to capture this. Instead, we are left with the idea that she is a lone voice that nobody is seemingly paying attention to. The couple surrounded by plastic containers are part of a familiar group who drink the spring water from the well at the centre of town. As a Spa town, the consuming of the waters has been a fixture for over a century. These people are clearly taking it seriously judging by the number of containers. I loved the irony of their drinking takeaway coffee in preparation for collecting their water.

Overall, I am glad that I took the decision to try something similar to Evans but with that unseeing perspective. It had the same ‘hit or miss’ element to Evans in that I couldn’t guarantee what would be in the frame, but because I wasn’t actually watching my subject I feel there is a complete detachment between us. Yet, the impression that I have of the people of my town is reflected in the images when collected as a series. The main challenges with the exercise were technical, but I guess also my reluctance to put myself in a difficult position also drove me down this path. No doubt I could have shot better photographs technically with one of my proper cameras, but I am pleased with how the mobile phone performed here.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2021, “2) Project 1 – The Unaware”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/05/24/2-project-1-the-unaware/

[2] CIACART, 2018, “Interview. Philip-lorca diCorcia”, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67U-0_wExLA

[3] BBC, 2007, “The Genius of Photography”, Television Documentary, BBC