Introduction

In this post, and the accompanying Padlets, I revisit two of the sources texts in more detail. My broad theme of Communication was explored in the context of the genres of Documentary and Portraiture in Part 3, because at first glance the ideas of the history of culture, technology and identity was felt to fit naturally within them. In this project though, the ideas of how landscape is both defined and affected by mankind, as well as the inverse impact on our behaviour are presented. This offers a whole area to research, starting with Source Text 1- Colin Pantall’s lecture on The Way We See. As I have been considering how my theme could become a focused project, I’ve thought about cultural perspective and the potential audience for the series. When reading the source texts, the other work that stood out to me related to ideas of representation, being inside the culture or observing it. This picks up on the ideas of Insider/Outside that Martha Rosler discussed in her work in the Bowery district of New York. Chris Coekin’s work Backwards and Forwards in Time is the second Source Text discussed here.

Colin Pantall – The Way We See

During the course of the lecture, Pantall poses a series of questions. I’ve condensed them into a single question for each section of the lecture in order to address them here.

- How are maps used now and how, if all, do they affect how we experience a place?

- When considering a beautiful, picturesque or sublime landscape, are there any problems with tending to the beautiful?

- Does the wilderness still exist and can a landscape be tamed by the photographer?

- How can photography be used to record the changing landscape and is it capable of driving real change?

- How does a landscape make us feel and what tangible elements are there that contribute to this comfort?

Padlet: https://oca.padlet.org/richard5198861/dc24mgyzgc4egcf9

Response

This source text covered a lot of ground, but the first and perhaps most obvious lesson was that the landscape is something actively defined by the viewer, rather than being something that generally surrounds us. Landscape as a photographic construct says much more about the environment and culture of a region `than just what is contained the aesthetic. When considering place, we use technology to inform us both how to travel and what to expect when we get there. The former is the rise is popularity of digital maps such as Google Maps and Google Earth. The latter is provided by the shared experiences of others through review sites and social media. Where traditional maps told us about what was important to our national identity and culture, we have the rest of the internet to use for the same research. Our ideas of what a landscape looks like come from the picturesque imagery that is produced as a byproduct of tourism and aesthetic visualisation by some photographers. It makes us want to seek out the views that we are presented with so that we might have that same experience. In the case of Jacqui Kenny who suffers from agoraphobia, the artist uses the millions of available snapshots available as part of Google’s Street View to explore places that are not physically accessible to her. The photographic process is more akin to curation as Kenny suggests [1], but in a way the process she uses to review the images is akin to being present in the scene. She is a cold observer, able to draw her own conclusions about the environment and its people by incorporating the appropriate visual elements to convey some form of meaning from her work. Her work tends away from the traditional notions of aesthetic beauty in favour of some statement about human life in the landscape, which is more in keeping with the New Topographics ideas of the 1970s than with the early landscape photographers. This movement invoked as sense of irony for me about Ansel Adams. In his quest to capture the beauty of the wilderness and protect nature, Adams actually contributed a cultural idea of what wilderness was. The creation of the national parks in the US had the effect of preserving an aesthetic idea of wilderness, while inviting people to go visit. This explains the complexity of the definition within The Wilderness Act (1964), which sought to appease both sides of the argument over it being purely natural or influenced but culture. The proof that Adams’ was applying his own ideas to landscape comes from his production of thousands of different prints from a single negative. In the example of his famous Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941), the emphasis of the elements in the composition changed from early to late prints. The acknowledgement that man changes the landscape led to the rephotography projects that set out to highlight the negative side of our existence. Photography is used in this case to document the damage, but also on occasion, the progress – Sebastio Salgado is the notable example with his ‘rephotography’ of his rainforest reintroduction project. In other cases, such as Nick J Stone, rephotography documents how things can be redeveloped. His Ghosting History images show us how things changed after the Second World War, but in a way that is familiar to us. Familiarity is one aspect of our comfort with the landscape that is inextricably linked with our identity. In Britain, the recognition of a street that hasn’t changed that much since the war, but has overcome the damage in the overlaid photograph gives us a sense of comfort. Comfort is associated with well-being and while the idea of the natural landscape being peaceful and somehow nourishing is well established, a city landscape or a space that creates strong memory and postmemory is equally comforting.

The interesting learning from this source text is how landscape connects with ideas of identity and the human experience. The former is something we would traditionally associate with portraiture, while the latter is more closely linked with documentary. In both cases, the exploration of how the landscape is theoretically and physically formed by our need or desire from some ‘value’ has led to explorations of our own behaviour. Whether the documentary of potential resources as with Timothy O’Sullivan or the way an urban district takes on a sublime feeling in Sibusiso Bheka, the relationship between man and landscape remains at the heart of photographic practice.

Chris Coekin – Backwards and Forwards in Time

This source text took the form of a Padlet that describes Coekin’s background, influences and three of his works, Knock Three Times, The Hitcher and The Altogether. I’ll be exploring his works and the connections to his influences, both historical and contemporary.

Padlet: https://oca.padlet.org/richard5198861/9sz8id40r5k1icss

Response

As the title of his Padlet suggests, Coekin’s work explores the traditional ideas of class culture through a number of documentary series. He achieves this by exploiting the main visual codes in each of the major genres to produce work that spans them all without drawing the viewer’s attention to any particular classification of the images. What is most interesting to me is the use of candid and staged portraiture, the former being akin to the snapshot that has been perhaps the most popular use of photography since its invention. We all recognise the style of the snapshot; the lack of direct engagement between photographer and subject, the use of flash that appears to be difficult to control with it’s washed out highlights and dark shadows, and the subject appearing to be ‘doing something natural’. In his use of snapshots in Knock Three Times and The Hitcher, Coekin introduces a sense of being an observer. In the former, his images capture the members of the club chatting, drinking and even leaving their gathering. Coekin is watching, rather than taking part. On image of a man urinating provokes the viewer in thinking about this voyerism; such an image would not be something most people would consider shooting as it’s an intrusion on a private moment. It contrasts with a similar image in Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependence (Goldin, 2012, p.74) which, apart from being far more explicit, reveals a definite connection with between artist and subject. The other style of portraiture in Coekin’s series’ are posed or staged. In The Hitcher, the artist asks for a staged portrait of the people who picked him up while hitchhiking. These pictures provoke a variety of emotions within them, ranging from the appreciation of being noticed for the act to the discomfort at the highlighting of the deed. In some cases, the artist’s direction can clearly be seen as with the image analysed in the Padlet. However, this is most evident in The Altogether, which is stylistically similar to the work of August Sander. Where Sander was looking to document people and their professions, Coekin’s work is more contradictory to the stereotypes of the working class factory worker. They appear in combative stances, comradely group shots and with iconic ideas of struggle factored into the pose. For me, the combination of the two styles of portraiture add to each other, much as in Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home. However, I get more of a sense of exploring the artist’s feelings about their own experiences from Coekin’s series’, particularly in The Hitcher, where he places himself in the centre of the story and explores modern society’s view of the age-old tradition of hitchhiking. In all of the works here, Coekin uses his own experiences to influence how he represents the subject, but achieves this by being both participant and casual observer through his use of portraiture. The series’ also include still life, which Coekin uses to punctuate the narrative. In Knock Three Times, we see the elements that characterise the idea of a working men’s club (drinks and empty glasses, snooker tables, beer mats etc), but we also see traces of the people who were using them. In The Hitcher, the still life images of discarded items at the side of the road, speak to the current state of our environment and infrastructure. In one picture, a dead rabbit is shown between the kerbside and painted line of a road. The animal is arranged as if viewed running, while the line has an imprint of a vehicle tyre in its surface, likely made when the paint was still wet. The image’s potential narratives about the threat to wildlife caused by the roads, the way it should have been ‘safe’ where it was and the correlation with the dangers of hitchhiking are palpable. In one picture we see the fact that countryside is a dangerous place and that the romantic idea of wandering the roads doesn’t necessarily translate into modern times.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are a number of key points to consider from these source texts in terms of my own work. They are:

- How we see the landscape is very much driven by both our place within and our perspective on what is happening to it. We might recognise cultural or historical significance to an aspect of landscape, how it has changed over time and concern for its future. These are strong drivers for how artists and photographers represent landscape.

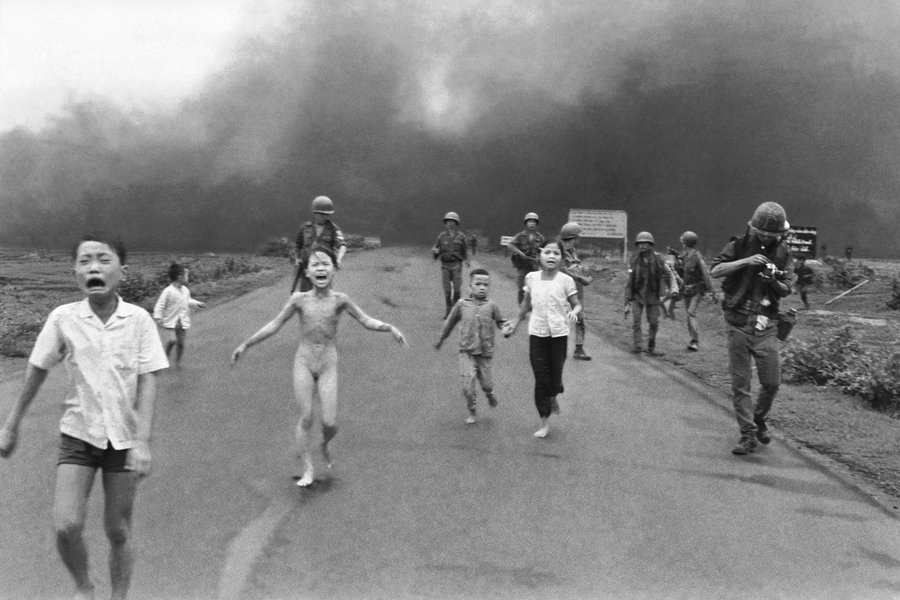

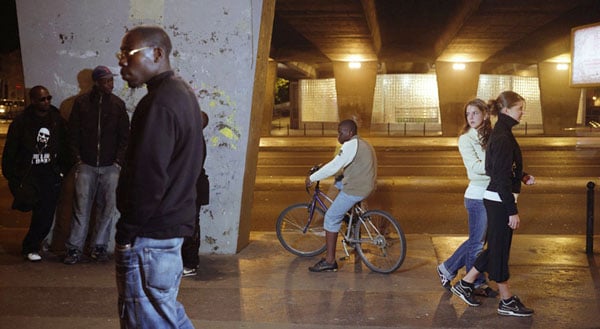

- A landscape can be defined by its people in a way that doesn’t, at first glance centre on the landscape. For example, an image in Mohammed Bouroissa’s Périphérique that is described in Pantall’s lecture, is referred to as landscape despite the main subjects being the people in the frame. The region in Paris where the images were set, has gone through significant cultural, racial and economic change which Bouroissa represents in a series of mise-en-scéne photographs. This question about how an image is identified within genre is something I want to explore in Part 5 for the critical essay.

- In a similar way to 2), the work of Sibusiso Bheka highlights another aspect of landscape in its treatment of an urban environment at night. The behaviour of the people and the way the images are lit by the artificial light coming from houses etc, all serve to create a sense of the sublime. Where sublime landscapes tended to centre around the alluring threat of the natural world, Bheka’s pictures drop the viewer into a potentially dangerous, yet fascinating night scape.

- Within the portraiture genre, the methods for making pictures vary along with their interpretation. Snapshots and staged portraits combine well in Coekin’s and present the viewer with a perspective driven by the artist’s connection with the subject, as well as an detached observer.

- Including still life in a series can add a form of punctuation to the narrative. In the case of Coekin’s work, the still life adds the situational information, whether supporting or challenging a known stereotype such as the working classes.

This has been an interesting exercise in terms of seeing how the visual codes from a genre aren’t always read a certain way, how our own identity affects how we might represent a subject and how the technical approaches within a genre can be used to achieve different, but interconnected meanings.

References

[1] DenHoed, A. (2017) ‘An Agoraphobic Photographer’s Virtual Travels, on Google Street View’ In: The New Yorker29/06/2017 At: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/an-agoraphobic-photographers-virtual-travels-on-google-street-view (Accessed 17/08/2022).

[2] Goldin, N. (2012) The ballad of sexual dependency. (2012 reissue) New York, N.Y: Aperture Foundation.