Introduction

I’ve recently received feedback on my submission for Assignment 4: A Picture Tells a Thousand Words [1] from my tutor. The assignment was an essay critiquing a photograph of my choice, which followed on from the work on semiotics in Part 4. I had chosen Philip-lorca diCorcia’s The Hamptons (2008) from his series East of Eden, which depicts a pair of dogs apparently watching pornography on TV in a living room.

The feedback was very positive with regard to both the written essay and the research that I had done in preparation for it. There were a couple of recommendations for additional research that came from the feedback report, which I will address in this post.

Annotating the Photograph

“I also really like the way you’ve pointed us to your ideas by writing on your chosen image, using red and blue markers to point to your working methods (these reminded on Wendy Red Star’s wonderful recent works where she made her own annotations onto archival photographs onto portraits of her American Indian ancestry (see here: https://aperture.org/interviews/people-of-the-earth-wendy-red-star/ )”

First observation from my feedback report on Assignment 4

What I love about this course is the way that seemingly innocuous connections often lead to my discovering a completely new artist. I had realised during the assignment preparation that I could import a photograph into an application on my iPad and then annotate with the device’s graphics pen. It meant that I could carry out my analysis of the signifiers and connotations and write them on the picture itself rather than in a set of accompanying notes. As well as reacting positively to this technique, my tutor pointed me at the artist Wendy Red Star, who incorporates similar annotations in her mixed media art.

Wendy Red Star (1981 -)

Wendy Red Star is a Native American artist who grew up as a member of the Crow tribe in their territory in Montana. Her work to rediscover, explore and publicise her people started as an undergraduate in Montana when she erected teepees in the grounds of her school[2]. She had recently learned that the school was in Crow territory and that all traces of her people living there had essentially been wiped away. This early act that was perceived as a political statement set Red Star on the course of creating work that highlighted the Crow against the backdrop of American colonialism. By its very nature, it is considered to be a political statement, something that Red Star denies is her intention. However, the work has found new importance within the context of the current climate of interracial tension in the US.

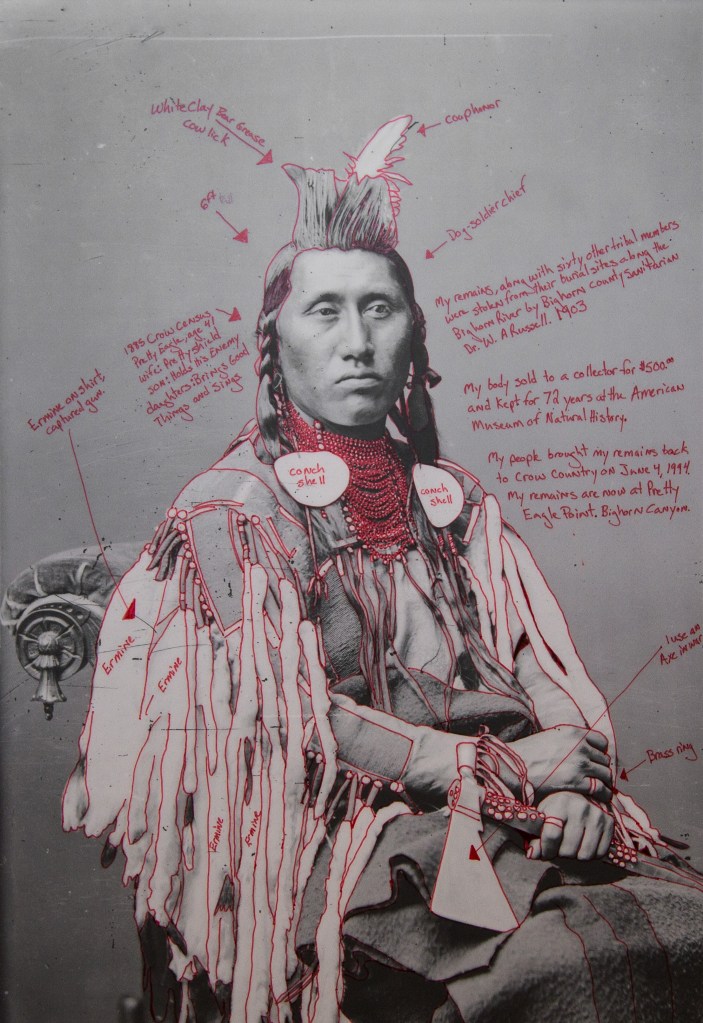

The work that my tutor made me aware of was Red Star’s series of photographs called 1880 Crow Peace Delegation. The photographs were taking 140 years ago when a delegation of Crow chiefs were invited to Washington by the President to ‘discuss’ the building of a railway link that would run through their lands. The discussion was essentially a way of colonial America to tell the Crow people that it was happening and that there was little they could do about it. In an interview with SmartHistory.org [3], Red Star tells of how the tactic being used was to invite the Crow half way across the country (taking many days) to the nation’s capital where they would be intimidated by the technological and military might of the white man. What the Americans didn’t realise was that the Crow chiefs were well aware of this and to counter the sense of intimidation, turned up to the negotiations in full tribal dress. The photographer, Charles Milton Bell, took a series of portraits of the chiefs in the traditional seated poses that were fashionable in the early days of photography. Bell’s images are cold and distant, as if there was little or no connection between photographer and subject – this was something he was well known for. When Red Star looked at the images, she saw the intricate details of what the chiefs were wearing. She went on to discover more about the men in the photographs, even getting in touch with their direct descendent to gain more of an understanding of their history. Red Star added written contextual elements to the original photographs, tracing around the edges of the details to help the viewer identify with their meanings. An example can be seen below:

In this photograph we see Pretty Eagle, seated on a western-style chair wearing his traditional Crow clothing, holding an axe. His gaze is beyond the photographer and his expression fairly static. Typically the subjects of these early photographs had to sit very still as the exposure times were long even with the primitive magnesium flash of the time. Even taking this into account, his proud expression comes through in the composition, which ironically may not have been Bell’s intention, given the political circumstances that led to the chief being in Washington. What makes this image is of course how Red Star has annotated it with bright red ink. Her additions highlight the different elements that she thinks need attention drawing to them, e.g the ermine skins that hang from his right shoulder, awarded when an enemy weapon is captured. Other context is about the man’s life, with commentary on his wife and family in the top left of the frame as well as the story of his remains after his death on the right hand side. Red Star seeks to introduce the man behind the attempted propaganda of the original photograph, the result being an education to those who need it. Like the discussions about photography needing some visual tension that we encountered in EYV, this picture and the others in the series are difficult to ignore. The act of writing on the photographs makes the viewer stop, take time to read and then consider the meanings. In the same way that we have seen context used in this course, the viewer creates their own narrative of Pretty Eagle when looking at this image, which has its roots in historical fact. The added text essentially helps build a narrative about the character of these hugely misunderstood people. Red Star isn’t trying to be political here, merely giving a face to her people with the hope that the historical prejudices about their ‘savage’ way of life or their ‘red skin’ are debunked. The importance of her work clearly increases when we consider the extreme prejudice and fear in modern America. However, when I look at these images, I find myself focussing on the man’s face which has no annotation. The sense of ‘this is who I actually am’ is emphasised by the text but for me it really comes down to the way that the photograph was originally captured. The context here seems obvious, but the story still has space within which to develop because the central subject is captured in such a matter-of-fact way.

My tutor was relating these photographs to my use of annotation in the preparation for Assignment 4, where I identified contextual elements and potential meanings by writing on the original photograph. The thought was how Red Star’s work might influence my own, which is something I’ve been thinking about since our call. The key difference that I see here is that the original images were appropriated rather than created; the text seeking to challenge the seemingly obvious narrative about a Crow being exploited. For Assignment 5, we are required to ‘make up’ an image, so the text could be used to either help the viewer or distract them away from the obvious. As I have an easy way of trying this out on my photographs, I am intending to do so. Mixed media (as with Red Star’s work) isn’t something I even considered when deciding to study photography, so I feel that this is expanding the constraints of what I consider my creativity.

Censorship in Photography – when is art really pornography?

The second observation in my tutor’s feedback was that although I had touched on the way that artists have been misinterpreted as immoral or purveyors of what people believe to be pornography, I could perhaps explore how this has evolved over the years. We know that art is subjective within some established constructs, but how have our sensibilities changed with regard to works that we find cross the line between decent and immoral?

Pornography

books, magazines, films, etc. with no artistic value that describe or show sexual actsor naked people in a way that is intended to be sexually exciting:

Dictionary definition of pornography, Cambridge Dictionary[5]

At face value, the definition of pornography above makes complete sense. An item of media that has no artistic value containing content meant to be sexually exciting. I was quite surprised at how clear this definition is, however. If it’s true, how is it that we are surrounded by ‘racy’ material in classical literature or fashionable clothing that leaves little to the imagination? Is that pornographic? The key clue here is the idea of nakedness, combined with sexuality. Where these literal or metaphorical elements are combined visually or in our imaginations, the morality of the work is questioned. Take, for example D H Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which tells the tale of a wealthy woman who engages in a passionate affair with her gardener at the behest of her disabled husband. The story contains very graphic depictions of the couple’s sexual relationship and leaves the reader in no illusions of its physicality. The book caused outrage in 1930s society when it was published and in fact was banned in the UK until as late as 1960. The words, then create such a sexual reaction in the reader that unless they have no imagination, cannot help but get them sexually ‘excited’. This was the basic argument for its banning as pornographic. This too makes sense in a way as what is being depicted is sexual conduct between people, however to say that a piece of writing has ‘no artistic value’ is stretching the narrative to suit the ultimate outcome. This is where censorship has its origins – the protection of the people from that which subverts them in some way. In the case of Lawrence, it was fine for people to have sex but another thing entirely for them to read about it. The natural argument about protection of junior readers and the vulnerable is, of course a good one. It does seem like an extremely dictatorial process to ban the book in its entirety, though.

In the case of the visual arts, the arguments for censorship are even more clear. Now we have the actual representation of sex or sexuality presented to us to see for ourselves. Or do we? I mentioned two photographers in the preparation research for Assignment 4[6], Robert Mapplethorpe and Sally Mann, both of which have been either banned or criticised for the potentially corrupting nature of their work.

Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989)

Mapplethorpe was a photographic artist who came to prominence in New York in the 1960s and 70s. His work spanned many genres including still life and traditional portraiture, but it is for his images of nudity and homoeroticism that he is perhaps best known, both for their quality and controversy. His images of male genitalia and homosexual acts appeared to some as straight pornography, i.e. with no artistic merit beyond the simple excitement or repulsion of the viewer. However, Mapplethorpe was fascinated with sin and its conflict with what he saw as beauty. As he started to explore his own homosexuality, Mapplethorpe’s work addressed the male experience of sex and eroticism; it was controversial at the time and even more so after Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989. In 1990 a retrospective exhibition of his entire catalogue of work in Cincinnati resulted in an obscenity trial which centred on two groups of images in the collection. The first, Mapplethorpe’s collection of nudes and BDSM photographs were considered obscene for obvious reason. The second, a pair of nude images of children were seen as incredibly disturbing, drawing the conclusion in the eyes of the law that this was child pornography. The case against the organisers grew in strength with some politicians demanding that funding for the arts be withdrawn. The trial went down in history as a direct challenge of what is considered art, ultimately concluding that if a piece of work has artistic merit, it cannot be considered to be pornography. What the trial actually did was cement Mapplethorpe’s entire work into history and the allure of the artist remains to this day. What interests me about this attempt to censor the arts is that it completely overshadows Mapplethorpe’s talent for photography. His brother Edward, who worked in his studio at the height of his fame described him as not at all interested in the technical aspects of the craft [7]. Mapplethorpe instead saw the beauty in the subject and the way is should look when represented on film. His brother’s classical training in technique would bring the ideas to life more reliably than perhaps he could achieve on his own. When we look at his still life and less explicit nudes, we see a delicate respect for natural beauty that we don’t necessarily think of when we hear the artist’s name.

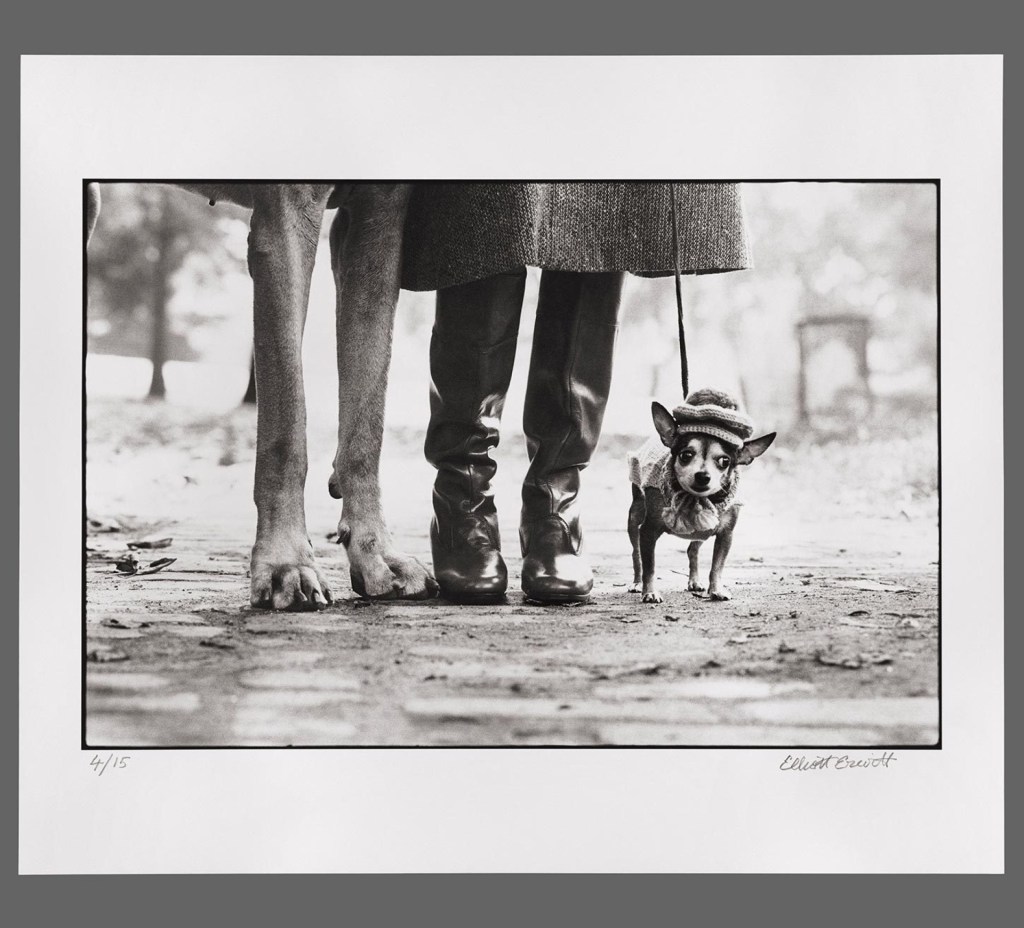

This photography of his then girlfriend, the singer Patti Smith is an example of one of Mapplethorpe’s nudes that creates a sense of vulnerability and beauty rather than being overtly sexual. The use of the natural light of the window and contrasting lines in the composition emphasise the natural beauty of Smith’s form which is curled in a sitting foetal position. I love this image because despite being simple in the way it’s constructed, it asks so many questions about what is going on for the model – what is she thinking and what happens next?

The other important aspect of the censorship of Mapplethorpe’s work is the suggestion by the trial that the artist had created child pornography. While the ultimate outcome of the trial was to dismiss this notion, the mere thought that it might be considered as such is deeply disturbing. The abhorrent nature of any form of child exploitation is never more greatly emphasised than by pornography, so much so that while reading about the obscenity trial, I decided immediately not to look at the works concerned and most definitely not to include them here in my blog. The thought made me physically sick despite the fact that they were ultimately considered to be art rather than porn. Naturally, what separates art from pornography is the idea of artistic merit which can come from multiple cultural and contextual elements in the photograph, for example a series like Nan Goldin’s Eden and After, which depicts children being children in many different ways is considered a loving tribute to them, in particular to those in her life (she has none of her own). Despite some of the images being of children bathing etc, and along with Goldin’s reputation for more adult material, the book is artistically a celebration of children that Goldin wanted them to take ownership of. There were no doubt some raised eyebrows however, but no gathering of crowds with pitchforks. How then, does the public decide? Why has Sally Mann being singled out for criticism of her similar images of children?

Sally Mann (1951 -)

We encountered the work of Sally Mann during the early exercises on light in EYV. A traditional large format photographer, Mann rose to fame with her portraits of her young family, which also drew criticism for its depiction of her young daughters as nymph-like beings. Some read these intimate portraits as sexualising underage girls, which led to similar accusations of pornographic imagery. Similarly, in Mann’s case the accusations involved children with the very real threat of Mann being arrested and charged. After being called out on her work by a preacher in Minnesota[9], Mann volunteered to talk to the FBI ahead of publishing her book Immediate Family. The conclusion was that the controversial pictures didn’t constitute child pornography by the FBI’s behavioural sciences. He went on to make the remark that while some people would potentially be sexually aroused by them, he had met people who had the same reaction to inanimate objects. There are many other anecdotes about Mann and the motivation behind her photographs of her children, but I was more interested in why people reacted the way that they did. Like Mapplethorpe and his shocking of the ‘decent, moral heterosexual’ people of American society, Mann’s pictures make people uncomfortable. In her book Pictures of Innocence: The History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood, art historian Anne Higonnet states that “No subject is as publicly dangerous now as the subject of the child’s body”. Rather than consider a mother wanting to document her children growing up through exploring their play, interactions as siblings and how they are within their environment, we instead focus on the fact that the hot summers of Virginia lead the children to often be nude. We believe that Mann is somehow exploring her own complex childhood and freely liberal attitudes through the exploitation of her kids, despite hearing from the artist that her children desperately wanted to be part of their mother’s work. The point on exploitation is further emphasised when we learn from her son that they were paid a few cents per negative[10], which in every other circumstance would be considered giving pocket money to a child. Most of all, the criticism of Mann as a ‘pornographer’ comes as much from the way that she is written about. In 1992, The New York Times published an article that explored many aspects of Mann’s life and work, including her controversial photographs of her children[10]. They gave the article the title The Disturbing Work of Sally Mann, which when reading the accompanying text, only accounts for a small part of the article. Perhaps then, we feel the need to assign some label to artists and work that makes us feel uncomfortable. The in-built discomfort means that we might acknowledge their existence but not wish to go further in understanding the context of what is bothering us. As with Mapplethorpe, my own limitations (and I consider them to be so), make me not want to include reproductions of Mann’s work in this post, despite my seeing nothing remotely sexual in the photographs. I guess we all have these limits to some extent.

Conclusions

This post covers two very different aspects of feedback from Assignment 4. I enjoyed learning about Wendy Red Star’s reclamation of her Crow heritage through annotating historical documents. For me, the pictures come alive with her additions and create a sense of who the subjects were, despite them being dead for over 100 years. In considering my own work, I can see some merits in using physical annotation to create mixed media art, but I think it’s probably a step too far at present. It has taken the past 2 years to think of myself as a photographic artist rather than an amateur ‘shot-taker’ and the conflict between my engineering brain and this new-found purpose is well documented in this blog. I will definitely be looking at other examples of mixed media in later courses as it is offers an original perspective.

The second part of this post deals with a subject that people don’t generally want to talk about publicly. Visual arts that include sex and sexuality do indeed provoke a response in the viewer, but is that pornography? Mapplethorpe’s work lifts the lid on a way of life and sexual practice that most are not aware of or wish to acknowledge, but where does the argument for ‘no artistic merit’ begin? What I realised from researching his work more deeply is that he was a great advocate of the beauty and danger of the human body, mixing perception of sin with the most natural resource we all have, our physical selves. I find some of his pictures shocking, but can appreciate the way they are shot and even deriving a narrative from them. What makes me sad is that his appreciation of his subject and talent for light and composition are completely overshadowed by the controversy and the way that his life was cut short so tragically by AIDS. The same goes for Mann. I find myself asking how any mother could create sexualising images of the children that she clearly loves very much. I know that such people exist in the world, but that vile underbelly of society doesn’t go about creating a carefully constructed documentary with a large format camera. We almost want to believe that someone is ‘not right’ when they photograph their children playing in the garden without any clothes. I think that says more about society than it does about Mann. The remaining sadness in her case is that her young children are now all grown adults and as such Mann’s work has since moved on. When we do a search of her work, though we are not directed at her intimate documentary about her husband’s debilitating illness or her beautiful landscapes. We don’t see her work about the effects of decay on the human body, we just see references to the controversy of her earlier work with her children. I come back to the original definition of pornography as being something that deliberately invokes sexual arousal, is graphically depicting sex and has not artistic merit. None of these apply to Mann or Mapplethorpe.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2020, “Assignment 4: A Picture Tells a Thousand Words”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/11/13/assignment-4-a-picture-tells-a-thousand-words/

[2] Griffiths M, Unknown Date, “Wendy Red Star”, Hundred Heroine website, https://hundredheroines.org/featured/wendy-red-star/

[3] Red Star W et al, Unknown Date, “Wendy Red Star, 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, Smart History, https://smarthistory.org/wendy-red-star-1880-crow-peace-delegation-2/

[4] Unknown., 2018, “1880 Crow Peace Delegation”, Image Resource, Birmingham Museum of Art, https://www.artsbma.org/1880-crow-peace-delegation/

[5] Unknown, “Dictionary Definition of Pornography”, Cambridge Dictionary Online, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/pornography

[6] Fletcher R, 2020, “Preparation for Assignment 4”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/11/13/preparation-and-research-for-assignment-4/

[7] Lee Ball A, 2016, “The Other Mapplethorpe”, The New York Times online, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/17/fashion/edward-mapplethorpe-robert-babies-brother.html

[8] McAteer S, 2013, “Patti Smith; Robert Mapplethorpe 1976”, Image Resource, Tate Online, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/robert-patti-smith-ar00186

[9] Gross T, 2015, “Making Art out of Bodies: Sally Mann Reflects on Life and Photography, npr online, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/405937803?t=1606894062435

[10]Woodward R, 1992, “The Disturbing Photography of Sally Mann”, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/27/magazine/the-disturbing-photography-of-sally-mann.html