Read the chapter ‘Photography and the Art of the Past’ in Hope Kingsley, Seduced by Art: Photography Past and Present (2012) Yale University Press, to read about comparisons between historical art and practitioners using Photography to offer differing challenges or explorations of art from the past.

- Make reflective notes on your reading and the comparisons that are being drawn in this chapter – add these to your learning log.

- Choose an image from Art History which you will visually respond to and reflect on your choice on your learning log (you might initially choose several before narrowing it down, and you can write about the choices and ideas you are considering).

- Developing your work from Project 1, make your own photographic image, or set of images that explores, challenges, or pays homage to the conventions and visual codes of the original image.

Reflection on Photography and the Art of the Past (Kingsley, 2012)

The essay begins by defining historicism as photography’s use of traditions from art history in terms of inspiration rather than straight reproduction or homage to the genres. I was struck by the popularity of art history conventions in modern photography with the examples given, although there is a definite sense that it is less so than the Victorian era when the ‘new medium’ of photography was in its infancy. The emergence of photography as a way of recording classical painting shouldn’t be a surprise, given the mechanical/physical processes it uses. What interested me was the move towards creating work that looked like them, not just in the visual aesthetic, but also the subject matter. Julia Margeret Cameron’s portrait Light and Love (1865) has the hallmarks of a Victorian portrait (black and white, the soft focus of old lens technology etc), but Cameron dresses her mother figure in a similar scarf to that used in The Holy Family with Child, by Bartolomeo Schedoni (c1613). Cameron was portraying the love of a mother for a child to the Madonna using a nest-like setting for the infant to belie the period the picture was taken. This idea of using the visual codes and signifiers that typically represent the Holy birth as the basis for what Cameron saw as every mother’s love for their child is compelling. This was the example in the essay that resonated with me, because although my modern reading of Cameron’s image is based upon the knowledge that photographers take inspiration from paintings, she was actually merely trying to produce a more accessible version of them using photography. Her contemporaries were similarly using the medium to effectively copy similar works. In doing so, they were able to recognise the style and techniques used in order to create their own original work. In the case of some artists, the paintings themselves feature in new photographic work. The essay discusses Jorma Puranen’s Shadows and Reflections (after Goya) 2011 which connects photography with the past through deliberately revealing the techniques used to make Goya’s famous portrait of The Duke of Wellington. The structures of the canvas and brush strokes, coupled with Wellington’s gaze from the portrait give a sense of intrusion into the making of the famous image, the sitter almost being exposed by the new perspective on the original process.

The main conclusion. from this essay is that modern artists are still inspired by the ideas and techniques employed in traditional painting, with some seeking to use the technical codes and some the iconography that was popular throughout art history.

Example for Analysis

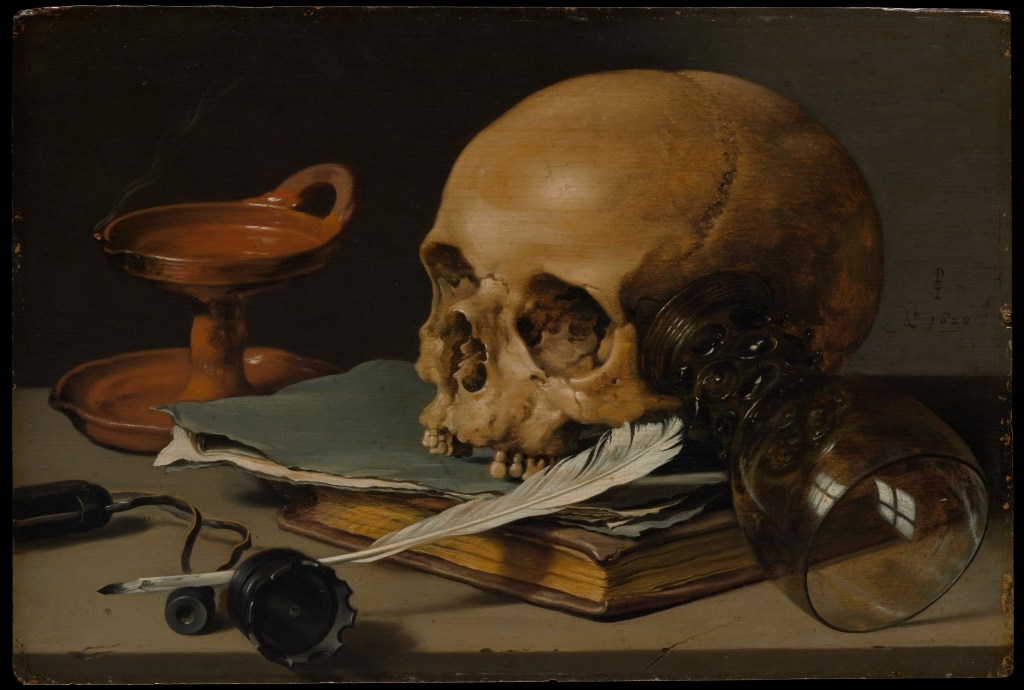

I have chosen a still life by Dutch painter Pieter Claesz (1597 to 1660 called Still Life with a Skull and Writing Quill (1628). The image is from the sub-genre of Still Life called Vanitas, defined as:

“A still life artwork which includes various symbolic objects designed to remind the viewer of their mortality and of the worthlessness of worldly goods and pleasures”

(Tate, s.d.)

Vanitas images deal specifically with mortality, with the reminder of the fragility of a life in balance. They almost always contain signifiers of the end of things, with skulls, writings, candles and empty vessels such as wine glasses to connote the impending. In this image, the dominant element is the skull, which faces the light. It’s condition with its lower mandible and some teeth missing, signifies age which ties in with our rational perspective on death – old people die. The empty candle holder is clean, which suggests it’s either never been used or has been tidied after death. This could connote regret for things not done or started during life or what remains of the flame once long extinguished. The skull rests against an upturned wine glass which is empty. This empty vessel points to previous pleasures, something that many Vanitas images have in common. Others contain musical instruments, food etc, all of which connote better times. The final elements in the image are the quill, the journals and the upturned inkwell. All of these signify labour and their aged appearance connotes something that has been done for a long time. The quill’s repose is such that the writer may be back at any time, or could have left for good. All of the elements are placed on a worn stone table or platter, which connotes the slow passage of time, but presents something familiar about the composition; the artist not simply presented disconnected items to the viewer.

Visually, the image contains elements that are all similar on colour and tone; there are not dramatic contrasts. This is reflected in the lighting, which owing to the lack of a candle is assumed to be natural. These images are deeply rooted in religious iconography so the choice of lighting could connote the ascension to the afterlife or the antithesis of the end of the day/end of the life.

This painting and the others of the same sub-genre appealed to me because they use still life in a way that I had not considered. Other artists were painting images of bountiful life, with exotic fruits, wines and flowers being the most popular themes. Vanitas serves as a reminder that things don’t last for ever and while often extreme in their execution, their style lends itself to story-telling.

My Image

Vanitas still life resonated with me because of the transitional messaging within the image. The ideas of being reminded of mortality while simultaneously celebrating the good things in life connected with a recent change in my own life. I recently gave up alcohol, not because of some problem, diagnosis or epiphany but more because of the way it, in small measure, become part of routine. Lockdown and changes in my working life meant that it was easy to indulge in the weekend treat more regularly than before. My decision to stop has had a huge impact on my wellbeing and made me reflective about the health issues caused by alcohol, some of which are very serious. I wanted to explore this with a Vanitas-style image.

Key elements to reproduce:

- Sense of warning represented in the paintings by a skull.

- Direction of light – ethereal and from above as if suggesting divine light.

- Enjoyment of life’s pleasures – hobbies, food etc.

- The sense of timing – being warned about the future, but also the present moment.

My Image

Analysis

For an analysis of my image using Barrett’s tools for critique, please see Padlet below:

https://oca.padlet.org/richard5198861/jq3akex618tt4xgr

Reflection

The combination of analysing Claesz and making my own still life that uses similar codes and ideas has given me a new perspective on the genre. More than the classical fruit scenes, the Vanitas still life paintings were multi-layered in their connotations, using signs that provoke a sense of dread in the viewer. They combined the artist’s skill in representing light with an understanding of form and luminance that draw the attention of the viewer to the powerful iconography. With my image, I tried to assemble a collection of items that paid homage to Claesz’s image, as well as recreating the directional lighting and matched tones. Once I’d included the camera as representation of ‘enjoyable pursuits’, I realised that there was going to be some diversion from the tonal qualities by introducing harsh highlights. When I realised this, I included my watch to add balance to the spatial composition. One element in classical still life that intrigued me was the use of candle light. For me, this was where the differences in the skills of the classical painters varied considerably. Some master practitioners, such as Rembrandt, really gave a sense of the scene being lit by this natural source, while others used artistic licence with the brightness of the flame and its fluid movement. That inspired my lighthearted criticism in including the flaming cocktail. I wanted the scene to appear to be lit by the flame alone and for it to look completely natural. For this, I used a slow shutter speed rather than a fast one to freeze the flame. The scene is fill-lit by a two strobes and a further LED with a warm colour temperature, which when combined with the key light gives a natural feel. The most important part of this assignment for me was the post-production analysis using the ideas of Terry Barrett, with which I was able to re-evaluate what I had intended to achieve with the picture.

“Thus, all photographs, even straightforward, direct and realistic-looking ones, need to be interpreted. They are not innocent, free of insinuations and devoid of prejudices, nor are they simple mirror images. They are made, taken, and constructed by skillful artists and deserve to be read, explained, analyzed and deconstructed”

(Barrett, 2006)

This assertion by Barrett resonated with me in Exercise 1[2], where I made the selection of the images from each genre randomly. At first glance, the Ansel Adams landscape is a beautiful representation, but by analysing using semiotics, a number of meanings could be derived from the elements and and what they connote. Barrett’s approach simplifies the reading of an image in my opinion, which makes it more intuitive to use.

In conclusion to this assignment, I am happy with my still life. I’ve received feedback from my peers about both the connotations of some elements and the relationship between my composition and that of Claesz. These observations lead me to think about how close to the original image my photograph is and whether that is important. Other feedback questioned how it fits with contemporary Vanitas works. I had partly been inspired to look at the still life genre after analysing Paulette Tavormina’s Banquet (2017) in Exercise [2]. Her use of including movement with the birds in flight, but in a staged fashion, led me to question the movement of candles in other paintings. By incorporating ‘real’ movement into still life, does it still fit with the codes of that genre? Is it truly ‘still’? Looking at Ori Gersht’s Exploding Flowers [3], where the movement from the dispersing petals is clearly there but frozen by a fast shutter speed, I would argue that it’s a difference in detail definition. My flame is clearly identifiable, yet the movement is more life-like owing to the longer exposure. Therefore in terms of being an homage to still life, and in particular Vanitas, I am happy that my image meets the original intent.

Against the Learning Objectives

LO1: Compare the theoretical features, characteristics and histories of different photographic genres.

The features of Still Life were studied in Exercise 1 and brought into this assignment.

LO2: Deconstruct a given genres’ conventions and create visual material informed by that knowledge.

Visual codes such as composition, lighting etc for Still Life were recreated in my image. I took the idea of Vanitas, a sub-genre of Still Life and made it about the warnings of health impact from alcohol instead of mortality. I used similar internal contextual elements as laid out in my post analysis in the Padlet

LO3: Produce new visual work informed by your research.

I produced an image that pays homage to Claesz’s work but isn’t a replication of it. The contextual elements are similar but the overall meanings that can be connoted from them lend themselves to my story.

LO4: Analyse the wider global contexts surrounding contemporary image making.

I was inspired by Paulette Tavormina’s Banquet (2017) which took the classical ideas of a feast in still life and incorporated a flock of birds descending to eat the food. The ambiguity of their presence (see Exercise 1) added a layer of narrative to the image, which in every other regard looked like a painting.

Figure Reference

Fig 1. Pieter Claesz | Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill (s.d.) At: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435904 (Accessed 14/05/2022).

Bibliography

[1] Barrett, T. (2006) Criticizing photographs: an introduction to understanding images. (4th ed) Boston: McGraw-Hill.

[2] richardfletcherphotographyblog (2022) Project 2: Exercise 1: Denotation and Connotation. At: https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2022/05/05/exercise-1-denotation-and-connotation/ (Accessed 22/05/2022).

[3] Mummery + Schnelle: Ori Gersht (s.d.) At: https://www.mummeryschnelle.com/pages/oriselector.htm (Accessed 22/05/2022).