Introduction

We are introduced to a number of artists who have used conversations or discussions to describe or invoke memories. As we learned in Part 3, memories can take the form of our own past experiences, those passed down through generations or even those that are created by a major cultural event such as The Holocaust or the assassination of JFK. The phrase “Do you remember where you were when…?” evokes memories that may not be our own but are our acknowledgement of what happened and the cultural circumstances that gave rise to it.

David Favrod (1982 -)

In his work Hikari (2014), Favrod addresses a single conversation that he had with his grandparents about the events and aftermath of World War 2 in Japan, which included the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in 1945. Favrod remembered this conversation that was never revisited or discussed subsequently and as he described in an article for LensCulture[1], he had borrowed their memories and used them for his own testimony. In doing so, he used an increasingly fading direct memory (as survivors of the war are dying out) to highlight his own coming to terms being half-Japanese and not being able to gain duel citizenship. The series combines different styles, ranging from straight documentary, through fictional and conceptual images. In each case, Favrod leaves a large amount of ‘space’ for the viewer to bring their own experiences to the interpretation. Some images are stark but conventional compositions, while others contain graphical annotations or text. Most notable is the shot below:

What is interesting about this photograph is not so much the desolate aesthetic, with the bright sun and rising smoke from what we presume is a fire. Instead the Japanese text that has been added is the representation of Baoummm, the sound that conjours the explosion of a bomb. As we look at the image, anyone who does not understand the inscription has the title to go by, which when spoken out loud phonetically describes an explosion. The rest of the image immediately suggests total destruction, which two cities in Japan suffered when the atomic bomb was used. The image now suggests that perhaps this landscape looked different before a catastrophic event with the remnants being the bright light of a fire and smoke on the horizon. The added aural information connects directly with the memory of Favrod’s grandparents and is constructed in a way that the noise could still be felt in the present. When we look at this image in the series, the duality of the narratives becomes more apparent. Knowing that Favrod tried and failed to become part of the culture that half his family were from, this shot takes on an empty, almost pointless feeling to it. The news would have been devastating, so the combination of the wasteland and the shock of the sound connect with his experience as well as that of his grandparents.

Another image that stood out for me was the one below:

Here we have a shadow puppet being cast onto a concrete wall and a title that suggests that it’s the wall of a bunker. In the interview with Sharon Boothroyd [2], Favrod describes the fact that in his home country of Switzerland there is a law stating that houses must have some form of underground shelter in case of nuclear accident. Knowing just this one piece of information through its title, we can read the image as being about freedom because of the symbolism of the bird ‘sculpture’ being made with the hands. When we add the context of Favrod’s duel citizenship issue, the image could take a more political meaning where the artist is being actively excluded from part of his ancestral heritage. However, we also have the anecdotal information about how the atomic bomb blasts scorched patterns of living things into walls and other structures owing to the intense heat. Now the image has a sense of duality about it that is influenced by the spoken word and historical memory more than the title. We’ve all been to a gallery or museum where an exhibition has a brief introduction to the artist or an audio clip where they introduce the series. These quotations or spoken words set the scene for the series before the viewer looks at the pictures and serves to provide a small amount of detail, the expectation being that viewer bring their own interpretation to the work. In the case of Hikari, the viewer doesn’t need to be experienced in Japanese culture in order to read the images. They could simply bring their idea of Japan in a similar way to the concept of ‘Italianicity’ in Barthes’s paper[3].

Sharon Boothroyd (1982 -)

In her series ‘If you get married again, will you still love me?’, Boothroyd attempts to show us the unspoken emotions experienced by children when their father is absent from their lives. Instead of straight documentary of a particular situation or reaction to it, Boothroyd takes a more constructed approach. In an interview with LensCulture, Boothroyd described how her discussions with separated fathers and their children, while revealing, didn’t uncover the truth about the pain caused by the situation. She decided to take the anecdotes from her interviews and create a series of tableaux to reflect her interpretation of the feelings the children were experiencing. Boothroyd tried to get inside the child’s experience and represent that in her photographs. The series doesn’t contain any additional context beyond the main title and it is up to the viewer to interpret the images in conjunction with it. Although many people don’t experience the loss of a father figure through divorce or separation, what is powerful in this series is that everyone has dark moments where they are isolated or anxious. For example:

In this picture, a girl and (we presume) her father are sitting in a cafe sharing a portion of chips. The immediate thing that we notice is the physical distance between the two and their total lack of engagement. Without knowing that the series is about absenteeism, it could be interpreted as a teenage daughter behaving like a teenager. However on close inspection there is a real difference visible in the expressions of the two; the girls anger and the father’s sadness. Now the image can be read as a drifting apart that a portion of chips isn’t sufficient to bridge. We can interpret the offering of food as a way of breaking the ice or diffusing tension, but also as a poor way of making an unhappy person feel better. Perhaps the gesture itself is what has made the girl angry. In my interpretation, I am conscious of my own experiences as a teenager which don’t necessarily reflect that of other viewers; this is the point of the series. The viewer brings their own empathy, intolerance or feelings of love, anger and sadness to their interpretation of the image with only the title of the series to go on. The learning point here is that we don’t have to include text to create an open narrative, but some small gesture of context-setting helps guide the viewer in their understanding of the work.

Kaylynn Deveney and Duane Michals

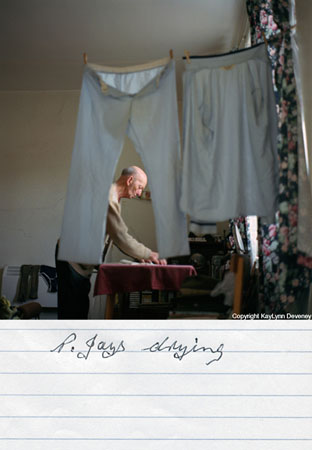

The next two artists we are introduced to have both made use of annotation in their works. Kaylynn Deveney’s series “The Day-to-Day Life of Albert Hastings” is just that. The artist got to know her subject, an elderly gentleman that lived in the same area of South Wales, and photographed him going about his day. While we have encountered a number of artists who have done this sort of thing, what is interesting about Deveney series is that it is annotated by the subject. In her introduction to the series, Deveney describes how she wanted to explore Albert’s experience of being photographed and how it differed from how she perceived him as a subject. When we look at the annotations that he added, we get an insight into his personality that supports the image. Some are banal, which is how Deveney describes the particular event being photographed, for example:

In this image, we have an interesting composition, with the subject framed by his pyjamas, yet he simply states the fact that they are drying. I find the brevity of the annotation interesting because when we look more closely, Albert is doing something else in his laundry. Although not entirely clear, he looks as though he is ironing some other clothes. This raises questions about how he saw this domestic activity and why when he looked at the print, his attention was focussed on his pyjamas. Elsewhere in the series, we learn that his pyjamas are a source of physical comfort to him, so perhaps this image can be read as him acknowledging his priorities rather than simply doing his chores.

Other annotations in the series are more humorous, with for example Albert joking about opening his veil-like curtains as opposed to talking to a ghost. Others go further into his philosophical side with notable example being a close-up portrait with the caption:

“Could this be a presumptive picture of my futuristic soul regarding a past world and friends?”

With the variation of commentary provided by Albert, we get an insight not only into his day-to-day life of chores and pleasures, but also his outlook and mood over time. Deveney states that she photographed him living in a number of flats over a couple of years and as she got to know him better, he started to open up about the past life he refers to above, providing the artist with family photographs, drawings and poems that he had written. All of these appear in the series, which further emphasises the sense of Albert’s identity without merely telling his story.

We discussed Michals’ use of text on a photograph in Context and Narrative[6], with the image This Photograph is my Proof (1967). That image showed a couple sitting on a bed in an affectionate embrace. The accompanying text stated that the moment captured was proof that the relationship was good at one point, which created a different narrative within the image. Now, instead of the joy read in the iconic message in the image, we have a reflection on a memory that is sad and regretful. The narrator is challenging the notion that their relationship had always been bad by pointing out something that visually proves it to not be the case. As well as invoking a sense of ‘I told you so”, the image also highlights our inherent belief that what we see in a photograph is the truth. Whatever the real truth of the situation being described, the image is presented as evidence even though the poses, expressions etc could be manufactured or exaggerated in some way. Michals uses text to help tell stories that are wrapped up in the journey of life towards death and his annotated series’ deal with related topics like reincarnation (The Bewitched Bee, 1986)[7]. In this example, Michals’ use of relay text invokes the emotions of feeling lost, found and then lost again, with the subject being transformed by a bee sting into a majestic antlered creature. When I first saw this series, I wasn’t immediately taken by the aesthetic quality of the photographs but by the way each picture built an emotional response throughout the sequence. Michals’ himself stated:

“I’m not interested in what something looks like, I want to know what it feels like.”

Duane Michals [7]

In my reading of The Bewitched Bee, I am bringing some of my own past experiences of establishing identity which in turn invoke memory and provoke emotion.

The Spoken Word

While each of these artists have exploited the written word in creating their narratives, the one that differs slightly from the others is Sharon Boothroyd. In her series, she used conversations with separated fathers to gather some questions that were asked by their children, which used as the background for her series. Only the title explicitly quoted the question, but the anecdotal spoken work comes through strongly in the images that make up the series. The common theme through the works of all of the artists is the power of the subject’s perspective, whether it is the interpretation of the memory of a conversation as with Favrod, or the actual writings from the subject as with Deveney. When an artist includes the subject to provide a commentary to the work, the resulting narratives can take on a wider meaning, as with the first example in the notes, Sophie Calle’s Take Care of Yourself. We first encountered this work in Context and Narrative where we explored Calle’s approach of seeking the views of multiple viewers to help establish the narrative. When we consider it in terms of the spoken word, however we can read more than just the opinions of individuals. Calle had asked a large number of women to read the break-up email from her partner and respond in some way. What she got back was a broad interpretation of the email’s contents, emotional reactions to the sentiments of its writer and suggestions about how to deal with it. The work’s title, which highlights a patronising platitude who’s use is somehow meant to placate the reader, suggested to me that the narrative was about anger and resentment at Calle’s treatment. However, now I read something else about our culture. The response are essentially putting the viewer in Calle’s place, asking how they would react if they’d received the email. The breadth of female solidarity comes through but the for me the more impactful element is how that is expressed. Modern society is much more expressive with the advances in communication technology, so people are almost less restrained when it comes to putting their view across. This is my experience, which when I bring to the viewing means that Calle’s work now takes on a sense of “is it just me or…?”, as if she is seeking some form of approval of her own reaction to the email.

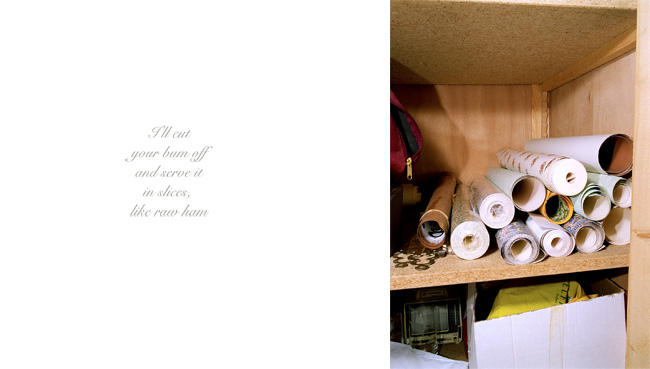

With Anna Fox’s My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words, the artist combines direct quotations from her father with the ordered, banal and almost claustrophobic spaces that her mother kept. Fox’s father was gravely ill and would verbally lash out at her mother and her regularly. The brutality of the rants and in many cases, threats of violence contrast with the domestic bleakness of the images.

What is most powerful here is the insight it gives us into a fragile relationship without either participant being seen. Where the other artists covered in this Project have used reflections on conversations and the real viewpoints of their subjects in their work, Fox creates a window for the viewer to see ‘what was really said’ by one spouse to another. Through that window we get a sense of the tension in the household, with domestic life continuing as normal as possible. We are left with questions about many aspects of the work that don’t appear as iconic context in the photographs. Was her father’s aggression wholly caused by his illness or was it endemic in their relationship? What was her mother’s response to the abuse? What kind of person was she and how did that affect Fox’s outlook on life?

Conclusion

In reflecting on the use of text either as part of or in conjunction with images, I can’t help but focus on the relative impact of words in invoking memory. Whether invoking educational memory, such as Lurpak’s clever use of strength and masculinity to create a sense of Viking or the Orwellian aesthetic of Kruger’s social commentary on gender equality, artists significanly increase the emotional connection with their work through words. This increases further when the text is derived from a living memory or sense of identity or empathy that the artist is still experiencing. Boothroyd’s approach of listening to the testimony of absent fathers and children allowed her to put herself in place of them both when creating her very precise tableaux. Deveney’s deeply moving documentary of the life of an elderly man is made more powerful when his perspectives on the images are annotated on them. In this case, the directly quoted words become part of the image itself, offering some insight into how Albert felt and what he thought about this project. In Michals’ work, his quest to understand how something feels overrides any sense of direct quotation, its loose narrative being relatable in many different ways without necessarily understanding the artist’s intent. Calle takes the broader reactions to her experience and presents them to the viewer as if to ask if they can empathise and even agree. With Fox’s series, the fantastical threats of violence collide with the banality of the images, with each entirely dependent on the other to have impact. What I’ve learned from this project is that the numerous ways we can pick up fragments or whole texts leaves plenty of room for us to bring our own experiences, but all the time there is a sense of legitimacy because someone else has spoken or written them. The originator is sometimes the artist and sometimes not. Either way, the inclusion of such text or speech connects us more with those people in a way that documentary captioning cannot.

References

[1] Unknown author and date, “Hikari – Photographs and Text by David Favrod”, Article, LensCulture magazine, https://www.lensculture.com/articles/david-favrod-hikari

[2] Boothroyd S, 2014, “David Favrod”, Blog Interview, Photoparley, https://photoparley.wordpress.com/2014/09/23/david-favrod/

[3] Fletcher R, 2021, “Research Task: The Rhetoric of the Image”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/11/05/research-task-rhetoric-of-the-image/

[4] Smithson A, 2012,”Sharon Boothroyd: If you get married again, will you still love me?”, Lenscratch Magazine, https://www.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/what-was-on/joan-fontcuberta-stranger-fiction

[5] Deveney K, 2001, “The Day to Day Life of Albert Hastings”, Artist Website, https://kaylynndeveney.com/the-day-to-day-life-of-albert-hastings

[6] Fletcher R, 2020, “2) Exercise 2: Newspaper Analysis”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/06/12/2-exercise-2-newspaper-analysis/

[7] Bunyan M, 2015,”Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals, Art Blart Magazine, https://artblart.com/tag/storyteller-the-photographs-of-duane-michals/

[8] Unknown author and date, “My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words”, Hyman Collection, British Photography.org, http://www.britishphotography.org/artists/15795/10316/anna-fox-my-mothers-cupboards-and-my-fathers-words-06?r=artists/15795/e/1916/anna-fox-anna-fox-my-mothers-cupboards-and-my-fathers-words-1999

Pingback: 4) Project 3 – Fictional Texts | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

I love Kaylynn Deveney’s series “The Day-to-Day Life of Albert Hastings”

LikeLike

Pingback: 5) Exercise 1: Still Life | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog