We are first introduced to the theories of art critic John Berger and academic Marianne Hirsch about the effect of photography creating instances where time appears to have stopped and how these moments grant us access to ‘memory’, whether direct or through our cultural experiences. In his book Ways of Seeing, Berger refers to photography as establishing the idea that a visual image is inherently connected with our concept of the passing of time, both at the point it was captured and from that moment onwards. He said:

“The camera isolated momentary appearances and in so doing destroyed the idea that images were timeless. Or, to put it another way, the camera showed that the notion of time passing was inseparable from the experience of the visual (except in paintings). What you saw depended upon where you were whn. What you saw was relative to your positon in time and space. It was no longer possible to imagine everything converging on the human eye as on the vanishing point of infinity”

John Berger, Ways of Seeing [1]

I interpreted this to mean that when a picture is taken, there are contextual and cultural references that are anchored at that particular moment which, if we were present during that period, we would recognise as contemporary. As time progresses, our interpretation of those elements within the picture change with our age, experience and environmental context that we bring to our viewing. Time continues to pass for the viewer but not the image, though the meaning of the image evolves with us. In considering this idea, I looked at this photograph from my family archive.

The image shows my late mother, my little sister and I putting up the Christmas tree in 1986. If I deliberately separate my knowledge of how it was taken, when I look this photograph I see the family collaboration, the dated clothing, my youthful (and characteristically grumpy) demeanour and my mum who has been gone for over 25 years now. Looking at this photograph through my adult eyes invokes many memories that I could attribute to this particular day, but in reality I cannot remember that actual event. In this case, then my recall is more about my memories of that time in my life rather than a detailed memory of the event itself. Hirsch takes the idea of memory further with her concept of ‘postmemory’. In an interview with Columbia University Press, she said

“As I see it, the connection to the past that I define as postmemory is mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that preceded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is to risk having one’s own life stories displaced, even evacuated, by our ancestors”

Marianne Hirsch in conversation with Columbia University Press, 2012 [2]

Hirsch’s book on the subject deals with Postmemory of traumatic events, in particularly the Holocaust, where the imagery and historical context create powerful memories that are not necessarily from our own personal experience. She argues that the viewer ‘invests’ in what they are seeing in the image, creating a memory that is almost fantastical given the lack of direct connection with the moment that has was captured. In addition, she points out that the more we create these inherited memories through imagery, the higher the risk that we remain dominated by them in the present. With something as traumatic as the Holocaust, it’s easy to see how that is possible, even with the right intentions around preserving the memory of its impact on the world.

With my image above, we have no eye contact with the photographer (my father), so little connection with the subject beyond his gaze on a family scene. It invokes memories in me because I am one of the subjects, but when I show it to someone who wasn’t there, e.g. my wife, she will only recognise her husband and sister-in-law as she never knew my mother. Any postmemory from the picture would be formed on her imagining what my mum was like using what I have told her over the past 20 years as context. In considering the other gazes introduced in the notes, the averted and direct gazes are perhaps the ones where I have experienced powerful reactions. For example, in Dorothea Lange’s famous Migrant Mother, the subject is looking past the photographer as if not noticing their presence. Her children are facing away so that their faces are obscured, which adds to the intensity of our reaction to her situation. We know that Lange was part of a group of photographers that were specifically hired to depict the impact of the Depression on rural people migrating to the more populated towns and cities, so the images are deliberately trying to tell that story of struggle. However, in this image I find myself asking more questions about how Lange felt when shooting this picture. I attribute this sensation to the lack of eye contact with between subject and photographer, creating a sense of ‘being observed’ or ‘attempted understanding’. When the gaze is direct, as in Steve McCurrry’s famous Afghan Girl (below), the connection between subject and viewer is direct, almost bypassing the photographer.

It’s so intense that the viewer feels directly connected with the unhappiness and distrust that her expression appears to convey. The gaze is emphasised by the girl’s intense green eyes which immediate create a sense of pride and defiance toward her situation and when considered in terms of the importance of the colour green in Islam [4], the image has many narrative layers. For me, the main difference is the seemingly absent sense of the photographer’s gaze in the image when compared with Migrant Mother. The observed element of the picture is missing because the direct gaze between subject and viewer is so vivid.

Keith Roberts – There Then, Here Now (n,d)

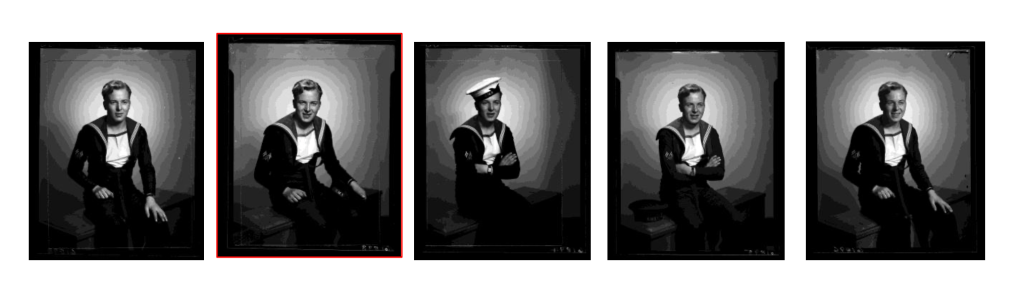

In his paper about a project he undertook with Edward Chambré Hardman’s archive of portraits that we have already discussed, Keith Roberts discusses the Hirsch’s concept of Postmemory alongside Svetlana Boym’s ‘The Future of Nostalgia”, first published in 2001. Boym takes the idea of nostalgia and breaks it into two forms, restorative and reflective. The former is related to a memory either real or passed down via a direct connection. For example I have a reflective memory of my late mother in the context of events such as decorating the Christmas tree in the photograph above, even though I cannot remember that precise occasion. A restorative memory would be more about the lives of my family during that period and the time that has passed since, with details contextualised in everything from the Western notion of ‘family’ to the Christian celebration of Christmas and all the traditions that go with it. For Robert’s project, he was using the groups of portraits of WW2 servicemen and women in Hardmans’ archive to explore the creation of Postmemory and the two forms of nostalgia within an exhibition of carefully selected images. The paper introduces the project but doesn’t discuss the outcomes beyond an interesting case study that emphasises the use of ‘gaze’. In his study of 5 images of a naval serviceman called Billy Walker, Roberts was able to first identify the image that Hardman had selected that best represented Billy (shown below with the red border). Secondly, he considered that image within the complete set.

Here we see Billy Walker shot in a number of different poses in his uniform. One of the shots has him wearing his naval hat, but the rest do not. He is smiling in each shot but only in the one that Hardman selected is he looking at the camera. When I look at this shot I consider my own family history with that period and in particular my awareness that so many servicemen were very young as Billy appears to be (he was 27 when he was killed a year after these portraits were taken). His happy looking demeanour contrasts with my own restorative nostalgia in postmemory regarding that period and his direct gaze makes my ‘investment’ in creating that memory more powerful than with the images where his gaze is diverted. Perhaps this was why Hardman, who was obviously experiencing the horror of the war at that time, thought this image was the best likeness of Billy and selected it for him and his family to own. Roberts contacted a direct descendent of Billy’s to explore whether his reflective memory, handed down through the family matched the restorative memory of selected photograph and to understand how it might differ. The copy of the paper the I have doesn’t reveal the answer, but the question is definitely interesting in the context of this project.

Conclusion

What has been interesting about this project is the idea that our memories can be an assimilation of stories and personal anecdotes passed on and developed over time, as well as formed through cultural context and classical documentary. The viewer connects with the subject in the portrait in some way and subconsciously uses this assimilation to ‘invest’ in the narrative. I think ‘invest’ is the perfect word for this process as it ties in with Barthes’ position on the effort the reader has to put into the narrative creation of what is essentially an assembly of cultural texts; see ‘Death of the Author’. The idea of reflective and restorative nostalgia for me emphasises the theories on post-structuralism where postmemory can be attained by a seemingly random set of ‘other people’s memories’ or cultural assertions. The intensities of these memories is heavily influenced by the gaze or gazes within a portrait as demonstrated by the comparison of Migrant Mother and Afghan Girl. Both are powerful, but in my case the direct connection with the eyes in the latter almost suspends my acceptance of it being a photograph. When I consider my response to it, I think there is both reflective and restorative nostalgia at play owing to the fact that conflicts in Afghanistan have been happening throughout my lifetime and still continue today. The connection to the gaze reminds me how young and vulnerable this girl looks at first glance, despite her probably not wanting to be represented that way. For me, this ‘memory’ invokes a reflective nostalgia both from news coverage and from my own childhood. In the photographs that have been studied here, gaze could almost be considered the volume control for the level of engagement with the subject and the subsequent postmemory that results from it.

References

[1]. Berger J et al, 1972, “Ways of Seeing”, quoted p18, para 1, Penguin Modern Classics

[2] Unknown author, 2012, “An Interview with Marianne Hirsch”, Columbia University Press, https://cup.columbia.edu/author-interviews/hirsch-generation-postmemory

[3] Simons J W, 2016, “The Story behind the world’s most famous photograph”, Image Resource, CNN Style Article, https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/steve-mccurry-afghan-girl-photo/index.html

[4] Beam C, 2009, “Islamic Greenwashing – Why is the color green so important in the Muslim world?”, Blog Article, Slate Magazine, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2009/06/why-is-the-color-green-so-important-in-the-muslim-world.html

[5] Roberts K, Date Unknown, “There Then, Here Now – Photographic Archival Intervention within the Edward Chambre Hardman Portraiture Collection (1923-63), Academic Paper courtesy of Academia.edu, Subscription Download

Pingback: Reflecting on Identity and Place | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog