Introduction

Following on from Exercise 3, we consider the idea of an artificially created background, the kind of which would traditionally be used in a studio environment. Studio can mean many things from a dedicated space in which professional lighting equipment and assistants work to shoot the picture, to a small corner of a room with a plain wall and some form of light source that works with the subject. My own experiences of studios tend towards the latter, with impromptu setups used to complete an assignment or project. I have the lights and equipment to shoot ‘businesslike’ portraits, but this post is about the use of such setups to create a series of pictures that reveal more about the subject than perhaps more clinical work.

Irving Penn – Worlds in a Small Room (1974)

Penn’s series Worlds in a Small Room makes use of a space in a room that has a background dressed for the portraits. The subjects are all shot within a small space with Penn not really trying to hide the fact that it’s a temporary studio. Penn used this temporary arrangement to then travel the world photographing people within his controlled setting. This approach offered Penn, who described himself as an ambulant studio photographer, a space that was both private and a known quantity. Although he used natural light for the portraits, he was able to control the highlights and shadows between shoots. The effect act it had on his subjects was one of neutral territory. Penn described his early engagements with some gypsies during a trip to Spain in 1964:

“The studio became, for each of us, a sort of neutral area. It was not their home, as I had brought this alien enclosure into their lives; it was not my home, as I had obviously come from elsewhere, from far away. But in this limbo there was for us both the possibility of contact that was a revelation to me and often, I could tell, a moving experience for the subjects themselves, who without words—by only their stance and their concentration—were able to say much that spanned the gulf between our different worlds”

Irving Penn[1]

As the shooting progressed, both parties became more comfortable with each other. The resulting portraits reveal the subjects in a way where the background context doesn’t really add anything to distract the viewer.

However, the idea that Penn’s studio was a neutral environment was challenged by scholar Jay Ruby at Temple University in 1977 [2]. He contended that the act of getting the subjects to relax was actually Penn asserting his control over the shoot. The studio, the arrangement of the camera etc were all the domain of the photographer with Jay suggesting:

“Stripped of their defenses these strangers would be free to communicate themselves “with dignity and a seriousness of concentration ” (p. 9). There is a fundamental flaw in Penn’s logic. While he was out of his culture in the sense that he did travel to these various locations, he always rented or constructed a studio to work in. The studio environment is one where Penn is clearly at home and totally in control. As wielder of the technology, Penn was literally calling the shots. The use of the portable studio offers a consistent background to the pictures that, like Evan’s Subway pictures, almost normalises the images in the series so we are no longer looking at it”.

Jay Ruby, 1977 [2]

When we think about this view, it’s the main issue with any kind of studio environment. I recall my own experiences of an art nude course that I did with the Royal Photographic Society in 2014. I had never done anything like it previously and my nervousness was a combination of operating professional lighting, directing a model and, of course her being nude. At the start of the course, my fellow students and I approached the shoot almost as children, asking the model for her help in posing and the tutor in terms of camera settings and lighting positions. With the increased confidence as the day progressed, we started to dictate the direction of the shoot. In my case, I started to break the composition rules that we had been told about regarding classic art nude photography, the two main ones being the model directly looking at the camera and smiling. The shot below is the picture I took that broke these rules, which the model was entertained by, but the tutor less so.

The point that I am making is that I have sympathy with Ruby’s viewpoint, but at the same time, Penn’s series documents the people of different cultures, some of which have either declined or may even have disappeared over time. Penn was fascinated with capturing and representing these people without any influence or interference. For me, the series works and is a great example of where to place the emphasis in portraiture.

Clare Strand – Gone Astray (2002/3).

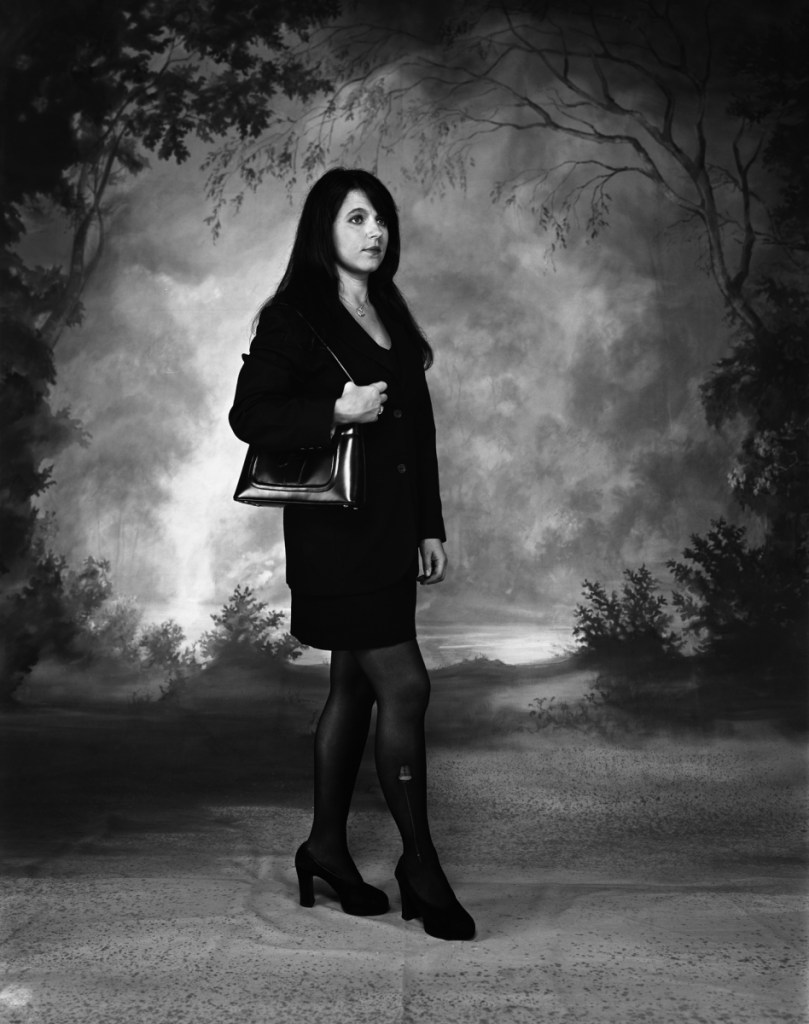

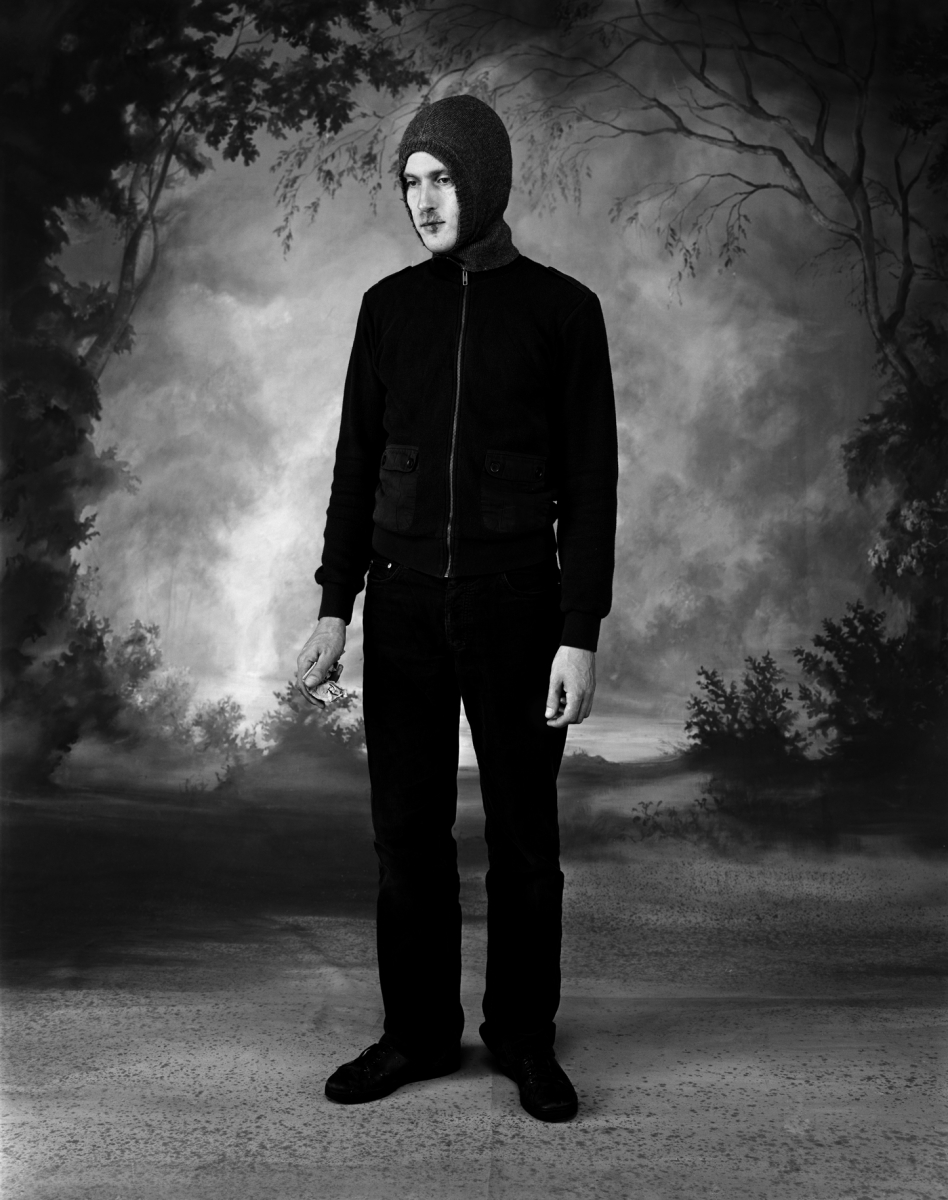

With Strand’s series Gone Astray, we have something similar to Penn’s work in the use of a single studio backdrop. In this work, the subjects are young people who look at first glance as if they have been brought into a studio to be photographed ‘as is’ by Strand. When we look closely however, we see that the subjects each have some kind of damage, either to themselves or their clothing that asks us to question how the series hangs together. Is it a series of random people that the artist has coopted to be in the photographs or is it a carefully controlled series of contextual elements that tells a story of the disaffected urban youth? The answer is, of course, that each image is staged as a series of cosplay situations with the props, clothes and poses being carefully stage-managed. Examples from the series can be seen below:

In both shots, the studio is used in the same way with the lighting adjusted between shots. The first picture shows a professional woman posed as if she is walking, perhaps to work or a meeting. Her professional suit is marred by a small tear to her tights, which is the ‘damage context’ for the photograph. For me, the way that Strand poses the model and her expression suggests some form of masquerade where the outer projection of confidence is flawed by the imperfect appearance of her outfit. Her expression though feels crafted by Strand, but this sense is revealed when we look at the images closely and for a time. Her use of context is all about the model, while the contrasting backdrop provides a more obvious thread that runs through the series. The same is seen in the second image, which this time is of a young man in a hoodie top, holding some folded money. This aesthetic is more in keeping with what we associate with inner city youth culture. Societal prejudices and media portrayals of young men dressed this way create a sense of being threatened. The inclusion of the money suggests perhaps some illegal activity where cash-only transactions are commonplace. Perhaps the suggestion is that the man deals drugs, which is a narrative that is supported by the other contextual elements in the scene. When we look closely, we see the flaw which is a cold sore on the man’s lip. Cold sores are a strange viral condition that affects people of all ages and social standings and are exacerbated by lifestyle, hormones and even simply being exposed to excessive sunlight. Here then, Strand is including a contextual element that both supports and contradicts the idea that this man is a mere hooligan. If we relate to the cold sore as a sufferer, we could then see the man out of another contextual situation. Perhaps he’s buying something else with his money. If he was set in a chemist, it would make complete sense that he would be buying medication for his condition.

In the same year, Strand completed a second part to the Gone Astray series, called Gone Astray Details. In this series, the duality of inner-city life and rural is much more subtle, with the compositions being much more surreal. An example can be seen below:

Here we have a portrait where Strand has dispensed with the studio background and instead shot in a natural environment. The man is standing in what looks like a gravel or well-trodden pathway where the only signs of vegetation are trampled sticks. The hint of the rural is overwhelmed by the smart, city attire of the man which makes him look like he’s not out hiking in the country. The inclusion of a small part of the informal jacket raises questions about who this person is in the context of this composition. Strand further includes a carrier bag decorated with butterflies which adds a contrasting element to the image. The butterflies juxtaposed with the bag, which looks like it’s made of plastic, points to the conflict of the natural world vs. the city. This work and the others in the series mixes the ideas of studio and street photography as the composition has both a sense of being ‘captured’ and lit by artificial light (the flash reflections in the shoes). When paired with Gone Astray Portraits. it’s clear that Strand is not being governed by a particular style and almost challenges us to question what is going on, both aesthetically and from a visual perspective.

Conclusion

I really like the combination of natural and artificial in both of these artists’ work. With Penn, the concept of moving the studio around the world to access a variety of cultures is interesting, achieves a consistent series of images that are anchored by the setup and reveal something of the natural personalities of the subjects. However, I agree with Jay Ruby’s view that the narrative is being controlled to a large extent by the photographer. With this perspective comes the sense that we are viewing different cultures as we might view a museum exhibit. I was reminded of my visit to The Horniman museum on Forest Hill, London [5]. Frederick Horniman’s vision was to collect and exhibit artefacts from around the world to better educate the poor and disadvantaged in Victorian society. The museum is perhaps best known for its extensive taxidermy exhibit which contains many species of animals from all over the world displayed by genus. It’s a fascinating exhibition which invokes feelings of Darwin’s documentary of evolution. However, when I visited I could only see the specimens in the context of their small differences intra-species, that is the way that their are only small changes that took many years to become noticeable. For me, Penn’s series is like this. It feels like the subjects are merely placed in a display cabinet. In contrast, I find Stand’s work more interesting. She places actors in an identical scene and tells a story that is clearly constructed, but also rooted in a perception of inner city life for younger people. Her use of obvious and subtle context to both support and conflict with our prejudicial assumptions about her characters leads me to want to look at the images more and more closely. Her use of the Dick Whittington-esq background is surreal but serves the purpose of anchoring the series as well as suggesting that the countryside is the nirvana that everyone aspires to. Clearly this is not the case for everyone, but again it plays into the hands of the media portrayal of the countryside being somehow better. I think that this sense of conflict and contrast is what I will take into my series for Assignment 2.

References

[1] McLaughlin T, 2015, “Classic – Worlds In a Small Room”, Image On Paper, https://imageonpaper.com/2013/07/21/review-worlds-in-a-small-room/comment-page-1

[2] Ruby J, 1977, “Penn: Worlds in a Small Room”, Temple University Paper, https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=svc

[3] Strand C, 2003, “Gone Astray Portraits”, Artist Website, https://www.clarestrand.co.uk/works/?id=100

[4] Strand C, 2003, “Gone Astray Details”, Artist Website, https://www.clarestrand.co.uk/works/?id=101

[5] Unknown, 2021, “Our History”, The Horniman Museum website, https://www.horniman.ac.uk/our-history/