Introduction

Our focus until this point has been how the portrait is a kind of relationship between the photographer and subject that is entered for a variety of reasons. In some cases, the relationship is purely transactional, i.e a payment or service is being exchanged that results in a picture. We have all experienced these situations during our lives, whether attending a studio or a wedding were there is a requirement to pose for a constructed shot. Another reason for the relationship could be purely artistic, with the photographer telling a story about the subject. We have covered this situation in Assignment 1 and Exercise 1 in this unit.

This project deals with the situation where no such relationship exists, i.e the subject is not aware that they are being photographed. In this situation, the photographer is observing the subject and deciding on how to represent them. We are presented with the quote:

“The guard is down and the mask is off”

Walker Evans (1938)

This is the obvious effect of shooting the unaware. There is no knowledge, pretence or preconceived idea of the image and we are truly seeing the subject in the context of their lives at that moment. We know nothing of the backstory that informs their expression or what they are thinking about when they are photographed. We do not know where they are coming from or where they are going to, just that they were photographed at a moment. The only control the photographer has is the decision to frame and shoot at that particular instant, which leaves their intention as well as the subject’s demeanour open to interpretation by the viewer. The act of photographing someone without their knowledge or consent has always raised questions about privacy and intrusion. In a similar way, photographing the unaware is as potentially socially awkward from that perspective, as asking a stranger for a portrait, which we did in Assignment 1. In this project, I’ll be looking at the artists mentioned in the course notes, many of which I’ve encountered before in my studies, but also more widely at the lesser known contemporary artists who practice this form of portraiture.

Walker Evans (1903 to 1975)

The first artist is Walker Evans, whose work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the 1930s we have already been made aware of. Like his contemporaries, Evans was on assignment to represent the suffering of the displaced agricultural people of the US during the Depression. His images were carefully stage-managed for that documentary work and the relationship between photographer and subject comes through. However as we discovered previously, Evans’ and the other photographers were heavily censored by their editor[1] to keep consistency with the story being told.

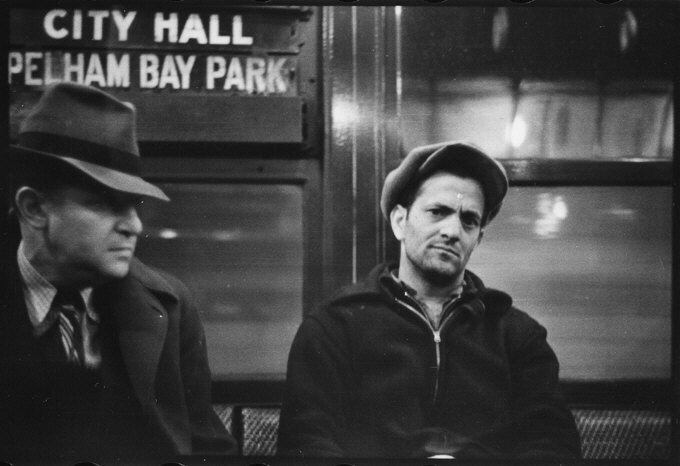

In the late 1930s Evans started to experiment with another form of portraiture, namely covertly photographing people on the subway. His portraits were shot with Evans’ camera hidden in his clothing with the focus and exposure predetermined. Evans observed his subjects and shot the pictures with a remote shutter release that ran down his arm. His pictures reveal people going about their business, mostly oblivious to what Evans was doing. In the example below, one of the people is looking directly at Evans, which suggests that he has noticed the artist looking at him. While he may not have been aware of the photograph being taken, it certainly looks like the subject had some inkling that something was going on. His concerned, almost disapproving expression takes on a different aesthetic to the man next to him who doesn’t appear to have noticed Evans’ gaze.

Evans collaborated with writer James Agee on the book Many are Called (1938) which was made up of a selection from the 600 or so images that Evans shot on the subway [3]. When we look at these photographs, we see a cross-section of American city life with no connection with each other beyond the fact that they are travelling on the subway. The common environment ties the series together, while the candid images of the subjects ask questions about what is going on for them, what they are thinking about and where they are going, both literally and figuratively. When I reflect on Assignment 1, the common environment that I used tied the subjects together but more loosely than Evans’s pictures. My use of the park and its vast space contrasts with the small confinement of the subway carriages. The background through the windows differs from shot to shot, but the subjects are framed by the architecture of the carriage, which I think stitches them together in a clearer way than my Assignment 1 photographs.

Martin Parr – Japanese Commuters (1998)

When I first saw this series by Parr, I was intrigued. I’m a big fan of Parr’s work because of his unconventional approach. His photographs have always felt like the artist’s very carefully considered observations and compositions are similar to many other artists, but his approach the technical aspects of shooting is a style that he’s made his own. His shots, particularly his portraits are often lit by direct flash and are very saturated. This style and approach doesn’t lend itself to discreetly photographing people without their knowledge. By Parr’s admission:

“I go straight in very close to people and I do that because it’s the only way you can get the picture. You go right up to them. Even now, I don’t find it easy. I don’t announce it. I pretend to be focusing elsewhere. If you take someone’s photograph it is very difficult not to look at them just after. But it’s the one thing that gives the game away. I don’t try and hide what I’m doing – that would be folly”

Martin Parr interviewed by The British Journal of Photography in 1989

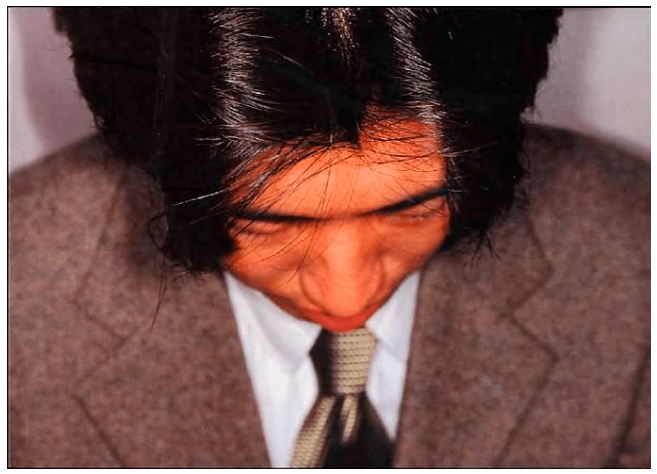

The other aspect that made me think twice about whether these were truly unaware arose from my own experience of Japan. The people are very guarded over their privacy, particularly on the subway where intrusion is something frowned upon by other commuters. I struggle with the idea that Parr was able to shoot so close to his subjects with flash and not have either them or the people around them know that it was happening. Perhaps instead some of the commuters were deliberately lowering their gaze in the presence of Parr rather than being asleep as is assumed/asserted. Whatever the circumstances, I am a huge fan of Parr’s work and style yet Japanese Commuters is my least favourite of his series.

In the example above, we see the subject looking down as if asleep. The frame is dominated by his head and chest and we see on a relatively small area off his face. However we can see a few details about the man, namely that he is wearing a suit and tie which suggests his is a professional of some sort. He is also fairly young, judging by his complexion and dark hair. Beyond that we can see little else in terms of context. The other portraits in the series are very similar in composition and reveal equally small amounts of context around the subject. I don’t like the series because for me it only raises two questions, the first about the wretched act of commuting which is suggested by the downward facing expression/sleep and the second being about invading people’s privacy by taking an extremely close, harsh photograph of them. The series feels more one-dimensional to me than Parr’s other work such as The Last Resort or Britain at Time of Brexit (covered previously in my research). I think that Michael Wolf’s series Tokyo Compression [4] offers more of an insight into the theme that Parr was exploring, but as we know some of the subjects were very aware of his photographing them through their abusive reactions.

Phillip-lorca dCorcia – Heads (1999)

In his series Heads, diCorcia set up a camera trap with remote controlled strobes set up under a building gantry. He used a telephoto lens from a fair distance from the trap which allowed people to see what he was doing., even if they weren’t sure what he was actually shooting. diCorcia then waited for people to walk into his trap, either by choice or by accident which creates a sense of blurring between ‘aware’ and ‘unaware’. Like Parr’s use of flash, diCorcia’s subjects would have known something was happening if they saw the light from the strobes, although in an interview in 2018 he stated that the flash was so fast that most didn’t notice[5]. With this series, diCorcia had many technical challenges caused by working from many feet away from the subjects. These included pre-focusing on where the subject might enter the frame which differed as their heights were varied. In addition to this, the people walking under the gantry were often in a crowd, so there were many shots where the subject was obscured by another person. This randomness reminded me more of Evans’ series on the subway because he could not frame his subjects beyond estimating the field of view of the camera and aiming approximately in their direction. diCorcia’s shots also raised questions about what is going on for the subject, what they are thinking about etc. as they walk the street. This was much more akin to Evans than Parr and Wolf.

Other Artists

Another artist we are introduced to is Lukas Kuzma, who’s book Transit is a collection of shots of commuters on the London Underground. When I look at Kuzma’s images I am reminded of a comment made by Joel Meyerowitz during the BBC documentary The Genius of Photography [6]. Meyerowitz would shoot on the streets of New York with his Leica film camera and frequently got close to his subjects, almost putting the camera into their faces. As the city is so densely populated, Meyerowitz asserted that they were aware of his presence but mostly couldn’t believe that he was interested in photographing them. The resulting photographs have the same ‘unnoticed observer’ feeling about them as Kuzma’s work. The photographer becomes a chameleon, just another person who is going about their business and not interested spectifically in the subject as far as they are concerned. The same sense of blending in is found in Tom Wood’s Looking for Love, which involved the artist spending increasing amounts of time being part of the same club scene as his subjects. Although they are aware of his presence, they are so accustomed to seeing him that there is no need to pay attention to themselves. The results are pretty close to natural.

These artists reminded me of an occasion where I shot photographs of the unaware. A few years ago, I photographed my friend’s vinyl record shop on World Record Store Day. The idea was to document the day where there is a greater focus on the medium and the revival of the record shop as a place to visit. I shot the pictures on high speed black and white film using my Leica M3. When I arrived to shoot, I was very uncomfortable with photographing people I didn’t know when they were minding their own business. Despite my friend and I agreeing on this being done, I wasn’t there in an official capacity, i.e. I wasn’t staff. After a few people being vocal about not wanting to be photographed, everyone started to become comfortable with my being there. I am also a vinyl fan, so I mixed the shoot with my own digging through the records. Eventually, I went unnoticed amongst the customers to the extent where they weren’t engaging with me at all. The resulting images were very natural in the way they revealed the people in the shop. A few examples can be seen below.

Conclusion

In conclusion I can see how the styles of photographing people without their awareness or participation has evolved since Evans’ subway photographs. His work is completely detached from the people sitting opposite him on the train, but he chose the moment to capture and therefore represent what he saw in their behaviour or expression. Looking at the work of artists that followed Evans in this area, we see the photographer becoming more bold in their shooting. Parr and Wolf’s photographing on the Japanese subway must have drawn attention, even if not from the intended subject. For me, this was a natural evolution from the increasing amount of street photography over the latter half of the 20th Century. People became accustomed to some intrusion from photography and they could choose to ignore or confront it as seen in both Parr and Wolf’s work in Japan. The further evolution of shooting the unaware is when the photographer becomes part of the background or activity. Kuzma and Wood’s active participation in the environment helped them disappear from view which allowed the subjects to continue to be themselves. These photographs have a different aesthetic to Evans’ original work in that they reveal the subject from different angles, distances and situations. The overall effect is the same, though. In each series, the photographer tells a story of what it’s like to travel around a city or party in a nightclub. The additional context that is available from the more contemporary approach perhaps leaves less to the viewer to work with. When I look at Evans’ pictures I want to know more about the people and what their lives are like. I don’t get the same sense from the works of the other artists.

References

[1] Fletcher R, 2021, “1) Project 3: Portraiture and the Archive”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/04/10/1-project-3-portraiture-and-the-archive/

[2]Editorial, 2013, “Walker Evans – ‘Many are Called'”, Image Resource, American Suburbx Magazine, https://americansuburbx.com/2013/05/walker-evans-many-are-called-1938.html

[3]Unknown Author, 2021, “Photographer Walker Evans in the Subway – Many Are Called”, Blog Post, PublicDelivery.org, https://publicdelivery.org/walker-evans-many-are-called/

[4] Fletcher R, 2021, “1) Project 2: Typologies”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/03/04/project-2-typologies/

[5] CIACART, 2018, “Interview. Philip-lorca diCorcia”, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67U-0_wExLA

[6] BBC, 2007, “The Genius of Photography”, Television Documentary, BBC.

Pingback: Exercise 2: Covert | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: 5) Exercise 2: Georges Perec | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog