Introduction – Archives of Photographs

Project 3 introduces portraiture in the context of the the photographic archive. We’ve been introduced to the archive in photographic art in the previous module. The archives studied were appropriated by artists who were not originally involved in their curation. Instead, they used the archives to describe intimate histories, whether related to collections of family portraits as in the case of Nicky Bird[1] or social history in the case of Broomberg and Chanarin [2].

Archive (noun)

“a collection of historical documents or records providing information about a place, institution, or group of people”.

Oxford Languages [3]

By definition, an archive is something that is deliberately collected by someone over a period of time. Some archives are highly ordered and managed as ‘records’ of a particular subject and some are merely a gathering of items that mean something specifically to the curator. The key learning from previous work on archives was that whether the former or latter, an archive of photographs cannot be purely objective in its representation of the subject. When a photograph is ‘taken’, the photographer’s intent, the social and cultural situation at the time and the process of producing the final image, all make the photograph subjective in meaning. In their conversation about the future of the archive, Anne Blecksmith of The Huntingdon Library, San Marino said to Tracey Schuster:

“Photography is inherently a product of its historical moment and cultural context; photographers choose, stage, and capture their images for many reasons, some of which they might not even be aware of”

Anne Blecksmith in conversation with Tracey Schuster of Getty, 2016 [4]

While we like to think about the objectivity of photographs, we know from previous work that they have individual subjectivity that is created by variety of elements. It therefore stands to reason that the creator or curator of an archive shapes what the archive is actually about.

Archive vs. Collection

A colleague of mine recently returned my copy of Finding Vivian Maier, the documentary film about the discovery and rise in importance of the work of the mysterious nanny/photographer[5]. The film tells the story of how John Maloof discovered Maier’s photographs when buying boxes of possessions from house clearance sales in 2007. Maloof ‘found’ over 100,000 photographs, negatives and even undeveloped films that were stored in a number of boxes, some with clear notes and annotations and others without. Maloof proceeded to collect as much of Maier’s work as possible and then create an archive of them. For me, this highlights the fundamental difference between a collection and an archive. Maloof was looking for historical photographs of Chicago for a research project when he bought the first box of Maier’s possessions. He became fascinated with the idea of uncovering Maier’s life through collecting more and more of her possessions, not limited to just her photographs. In trying to understand the person behind the collection of photographs, Maloof created an archive with the purpose of revealing who she was. His archive, made up of mixed media and other artefacts, tells us about Maier, but the large collection of her photographs has been archived with other purposes in mind. Maloof made the discovery (described in the film) that Maier wasn’t, as initially assumed, reluctant to show her work to other people, more that she wasn’t particularly organised when it came to editing her works into some form of collection for exhibition. Maloof has since curated an archive of her work with the specific intent to show her as a talented artist. What started as a disparate collection of photographs was now an archive who’s sole purpose was to exhibit and sell the artist’s work. Maloof has since found himself at the centre of legal challenges by Maier’s estate, which consists of the families of her friends that featured in her will and often the subjects of her photographs. Their issues with Maloof creating his own story of Maier and profiting from it have only recently been resolved, allowing for the continued promotion of her work. I believe that Maloof’s original intention was to uncover the artist, but that it quickly became more about his direction of her story than a documentary of her life.

Thinking about the Personal Archive

I started to consider my own experiences of photographic archives outside of my studies. Photography has been a significant interest in my family for many years, so naturally there have been many photographs taken over that time. Of the photographers in my family, the only professional was my Dad who ran his own business for a decade or so. A few years ago, he decided to have a clear-out of his office and offered me what he described as ‘family photographs’ he had taken throughout my growing up. What he actually gave me was all of his photographs, predominantly 35mm slides, which also included a great deal of his professional work. The interesting thing was how they were assembled as a collection. In those days, photography was all film-based and the cameras that were most commonly used were either 35mm or medium format, the latter being less popular among amateurs for economic reasons. 35mm films typically contained 24 or 36 frames per roll and when they were commercially developed, they were usually printed and packaged with the original negatives. With positive slide film the results were often mounted in plastic frames for showing with a projector onto a screen, but the same pattern was present; each package represented a window of the time taken to shoot a single roll of film. My Dad’s collection of over 2000 slides wasn’t an archive in itself, but represented two streams of time. The first was document of the family through the kinds of events where he would take his camera, e.g. holidays, birthdays, family visits etc and the second was the progression through his professional career via portraiture, model portfolios and his own art. When I thought about these two different collections, I considered the intent behind them. One of the films contained images of one of the holidays we took in France with another family we were close to and depicted us doing what one would expect, eating out, visiting local attractions, playing cards outside our tent etc. The images don’t describe the holiday as they document only a small part of the trip, much as stated by Jenkins in Project 1. However, even as a disparate collection they invoke all of the memories of that holiday for me without really telling a story. If I were to create an archive of all the photographs of our holidays, they would be part of a wider narrative, but in order to tell the story from my perspective I would be potentially editing out shots to focus on a particular aspect of the subject matter.

Mark Durdan and Ken Grant – Double Take (2013)

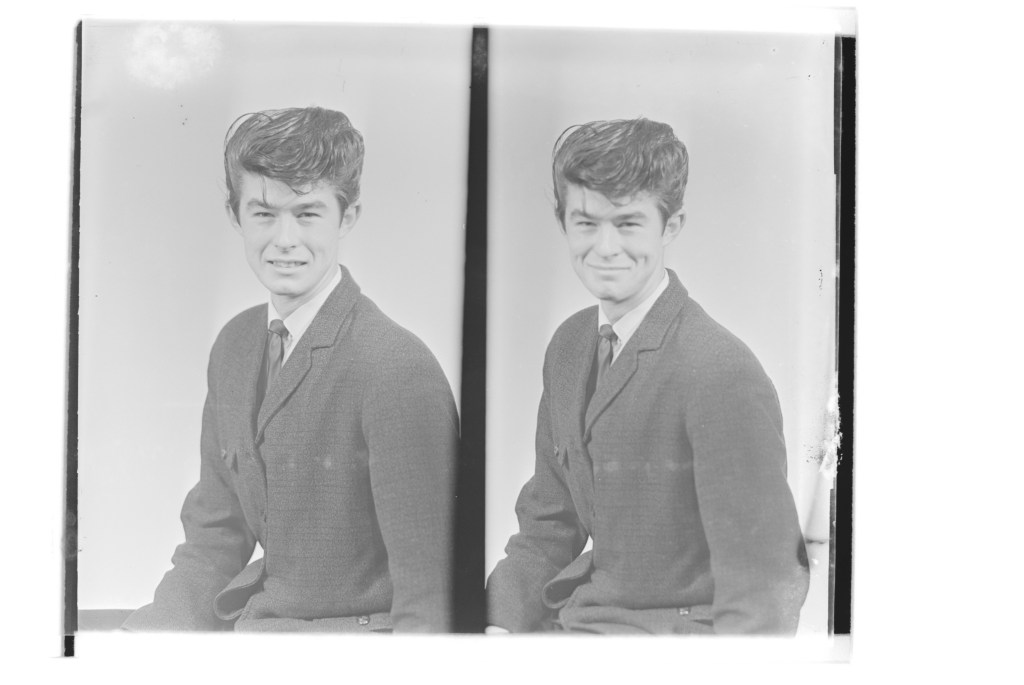

We are introduced to the work of Durdan and Grant, who created a series called Double Take from the archive of a commercial photographer called Keith Medley. Medley’s archive was donated to the Liverpool John Moores University by his family and contained thousands of negatives and glass plates shot in the 1950s. Double Take shows pairs of portraits that were captured on single glass plates in an effort by the photographer to save money. The fact that they are on the same plate means that they were shot very close to each other in time and when we look at them, we see the subtle differences between the poses and expressions of the sitters. Durdan and Grant saw this as being an insight into how ordinary people react to having their picture taken; the brief respite between shots being enough for either relaxation or becoming more tense. An example of a pair can be seen below:

Here we have a plate with two portraits of a man seated away from but looking at the camera. He is in smart dress and sports a typically 1950s hair style. In the left frame, he looks somehow nervous or uncomfortable with an almost forced expression on his face. In the time it took Medley to reposition the glass plate and shoot the second frame, the subject becomes more relaxed. Perhaps the photographer said something to him to get him to calm down or perhaps made him laugh. What we now see is a man with a smile on his face and a much more relaxed demeanour. The two frames don’t tell us much about him or about the era that he lived in, but they do show how people can shift perspective of emotion in the blink of an eye. As viewers, do we notice these subtle differences or changes in expression? How many do we miss?

Killing Negatives

The note go on to show us that Medley was a careful curator of his archive, defacing the images that he didn’t feel were good enough or had some issue that made them unusable. As Medley didn’t break up his plates, these ‘deleted’ frames still exist within the archive and Durdan and Grant use these frames as part of Double Take. The same control of the archive source material is said to have happened in the case of the Roy E Stryker, who curated the Farming Security Administration’s (FSA) images of the impact of The Great Depression. In this case, the negatives were rendered unusable by punching holes in them so that any print would include a dark circle somewhere in the frame. Emerson was manager of the project and hence controlled its narrative. Instead of defacing or ‘killing’ negatives because they were of poor quality or lacked impact, Stryker took this extreme form of editing to any image that didn’t suit the editorial. As a result, the archive that the FSA curated was very specific in what could be derived from it, but like the Medley archive the killed negatives were left as part of it. Once discovered, the printing of these ‘killed’ negatives takes on a different meaning, owing in part to the seemingly random nature of the punching of holes. A couple of examples are shown below:

In the first image, we see a farmer whose face is completely obscured by the punched hole. The man’s clothing and background suggest an agricultural worker or farmer clearly enough. Like Sander, the background showing a weather-beaten wooden wall indicates that this is a man who is not wealthy or anything other than working class. We would be right to question why Stryker censored this image in this way. Although we will never know because of the act of killing the negative, I suspect that the farmer was smiling in the original picture. Stryker may well have seen this expression as not lending itself to the narrative of the apocalyptic impact of the depression on the rural community. Indeed even when presented with immense hardship, some people are capable of incredible happiness and contentment. Here then, Stryker rendered this image both unusable and consigned its true meaning to the same fate by destroying the main subject. It’s clear from this that he wasn’t acting randomly at all, the alignment of the hole with the man’s features is perfect. By completely destroying the face, there is no crop or manipulation that can get back to the original sense of the portrait.

The second image is even more interesting. Here we have a black couple photographed on what looks like a bridge in a cityscape. The couple are looking in different directions, with the man engaging directly with the photographer while the woman looks off to the side. Both have expressions that look either angry or concerned, but we do not know why. Both are elegantly dressed, which suggests that they are relatively well off, yet somehow working class. Perhaps their dress is related to them attending an event or church service or perhaps they are the work clothes of people who working in some kind of service industry. The killing of this negative occurs centrally between the two figures rather than over their faces, which suggests that the Stryker was trying to ensure that the image could not be re-composed or cropped to achieve a result with them both in it. America was still a heavily segregated society in the 1930s, so the idea of including two healthy-looking black people in the narrative about the depression would have been unheard of.

What is striking about both images is that while there are clear reasons for Stryker not wanting to including them in the FSA editorial, both are without fault and are potentially interesting in their own right. The first is almost in the tradition of the portrait as Sander had been working only a few years earlier, while the second is a classic Walker Evans image, intriguing and natural. Stryker was ensuring that they were not just unavailable for his editorial, but also for any future publication. Of course, the work of artists like William E Jones[8] and Joel Daniel Phillips has brought the damaged negatives into their own. Now instead of the story that Stryker was telling, we can create a narrative about what was wrong with the whole FSA project as well as the cultural and socioeconomic issues of the 1930s.

Edward Chambré Hardman (1898 – 1988)

Hardman was a prolific photographer who’s career spanned the most significant period and events of the 20th Century and of the craft itself. In his lifetime he amassed a collection of more than 140,000 photographs that are now curated by The National Trust. His vast archive contains portraits of sitters taken many years apart and in the curated series Intermissions, they are shown together forming what is now called chronotype. An example can be seen below:

In this shot pair of portraits, we see a man in both his military uniform and also in later life dressed in smart civilian clothing. When I saw this photograph I was reminded of the portraits of General Grant from my earlier work [10]. The man is easily recognisable from his facial features even though his clothing and facial hair is different in both. However, when we look closer we see the way that the passage of time between the portraits has affected the man. He has increased in weight and his posture has changed with a more pronounce slouch in his shoulders. The muscle definition in his face as slipped as one would expect with age, and even though the portraits are shot with very different lighting setups, the man’s steely gaze seems to aged from one to the other. In the case of the Grant portraits, the famous General had led the Union army in the one and become US President in the other. His appearance changed in a similar way to the above pair of shots and, in the same way, the viewer has no real idea what has happened in the intervening years. Hardman’s portraits represent the subject at two points along his timeline but they do not represent his life in terms of history. The viewer is left to determine for themselves what has happened in his life over that period, with no additional context beyond the subject’s appearance and attire.

The strange case of E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville Portraiture

The final example archives being manipulated or damaged is that of E. J. Bellocq’s Storyville Portraiture from around 1912. Bellocq was a relatively unknown commercial photographer who made his living like many early practitioners by making documentary images. His clients were typically industrial businesses who wanted to record certain structures and landscapes for their own use. However, Bellocq was interested in portraiture and secretly worked on his Storyville series, shot in the prostitute district of the same name in New Orleans. Bellocqs portraits of the prostitutes are not seedy in any way, despite his inclusion of nudes. At the time, prostitution was legal but still seen as immoral by the general public, so Bellocq kept his work secret. When it was discovered after his death in 1949, it became clear that without these very imitate depictions of the workers of Storyville, no record of the area as it once was would exist. Interest in his series grew once the famous photographer Lee Friedlander purchased the plates and started to make prints from them.

Friedlander discovered that most of the plates had been damaged in some way to obscure some of the detail and to render them ‘unusable’. It is still a mystery as to who carried out this ‘killing’ of the plates, but there are theories as to the culprit. One theory is that Bellocq did the damage himself, possibly not seeing the value in the pictures or in some way to protect the identities of the women in the pictures [12]. Another theory is that his brother, a priest, discovered the images and defaced them because of their perceived indecency. Either way the act of damaging so many of them means that without Friedlander’s intervention, they would be lost. As with the previous damaged archives, the idea that the artist or someone close to them decided to change the story is in itself tantalising. For me, I’m simply glad that Storyville still exists as a sympathetic document of a lost area and history of New Orleans.

Conclusions

This has been an interesting research project. When I consider a collection of photographs such as the one I received from my father, I see something that has themes running through it but no real initial purpose behind their assembly in one place. We take pictures to capture memories, but actually the photograph itself merely helps invoke them along with the emotions and sensations that we can recall from an event. My Dad’s collection has no formal structure to it but certainly with my experiences of our family growing up, I could lay those images on a light box and quickly establish some kind of flow to them. It has always been a plan of mine to build a proper media library of the images for the future generations of my family to keep as a document. When I work on that project, my natural instinct will be to tell the story of the family through history. As we learned at the start of this unit, photographs don’t really serve as a statement of history unless they are part of a large number that describe something about a time and place. In my case, the archive could serve as a ‘historic’ document of my childhood, punctuated by the my memories that are perhaps incorporated as text. However, what has been interesting in this project has been what happens when a collection of disparate images becomes an archive in the hands of others. Now we have little or no connection between artist and the original intention of the photographer as in the case of Maloof and Maier – he built a picture of her life that in all likelihood would have horrified her if she saw it. His curation of an archive of her pictures serves to reveal the ordinary lives of her subjects, but he doesn’t know what motivated her to shoot her subjects the way she did. In the case of Durdan and Grant’s work Double Take, the artists add the act of undoing the photographers self-censorship by inviting the viewer to look at the subject in every context, even if the representation is flawed through the image being technically imperfect. In their work we see something about how people respond to having their portrait taken, even if they are a willing participant; the act of being photographed is not natural and this discomfort or awkwardness comes through in the series. The archive in this sense is just a vehicle for an alternative artwork, something that we see with the series’ created from the FSA images that were ‘killed’ by editorial censorship. In these damaged portraits, the viewer is being subverted by the removal of context and asked to consider what Stryker’s motivation was in his destruction of the works of other artists. The narratives that can be created from the killed pictures are now more compelling in the modern time than in the contemporary series that the FSA published. We see much more in the photographs than the stories of the post-depression migrants because of our reflective views on the issues of that time (racism, materialism etc).

Of the artists that curated archives of their own works , the most compelling one to me was Bellocq. The artist is said to have self-censored perfectly good glass plates by damaging them, which almost points to regretful reflection on his work. The idea that his puritanical brother further sought to destroy his work after his death because it was in some way obscene adds to the mystery of this particular photographer. When I looked at the Storyville series, I saw a combination of inclusion (being inside the culture – Bellocq was a customer of the girls) and of documentary of the livelihoods of prostitutes. The sub-narrative of seediness, moral judgement and shame was again more of a commentary on contemporary values of the time rather than of the subjects themselves.

My final conclusion from this work is to consider how I will curate my family archive. What story will I be trying to tell? Will it be how I remember it or will I invite the viewer to make their own mind up about the Fletchers?

References

[1] Bird N, 2006, “Questions for the Seller”, Artist Website, https://nickybird.com/projects/question-for-seller-2/

[2] Broomberg and Chanarin, 2011, “People in Trouble Laughing Pushed to the Ground”, Artist Website, http://www.broombergchanarin.com/contacts

[3] Unknown, “Archive: Definition of Archive by Oxford Dictionaries”, Lexico, https://www.lexico.com/definition/archive

[4]Peabody R, 2016, “What is the Future of the Photo Archive?”, Artist Interviews, Getty Blog, https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/what-is-the-future-of-the-photo-archive/

[5] Maloof J, 2014, “Finding Vivian Maier”, DVD release, Ravine Pictures

[6]Mulibrary L, 2013, “Photo Friday: Seeing Double Cost Effective Photography from Keith Medley”, Image Resource, LJMU Blog Post, https://ljmulibrary.wordpress.com/2013/05/17/photo-friday-seeing-double-cost-effective-photography-from-keith-medley/

[7] Image Resource, Unknown Date, “Killed Negatives: Unseen Images of 1930s America Exhibition”, Whitechapel Gallery, https://www.artfund.org/whats-on/exhibitions/2018/05/16/killed-negatives-unseen-images-of-1930s-america-exhibition

[8] Jones W, 2017 “Rejected & 3000 Killed”, Image Resource, https://www.williamejones.com/portfolio/rejected-3000-killed/

[9] Chambre Hardman E, 1923 to 63, “Intermission 01”, Image Resource, curated by National Trust, https://hardmanportrait.format.com/2318776-intermissions-01#12

[10] Fletcher R, 2021, “Project 1: Historical Photographic Portraiture”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/02/23/1-project-1-historical-photographic-portraiture/

[11] Editorial, 2011, “The Last Days of Ernest J Bellocq”, American Suburb X, https://americansuburbx.com/2011/02/e-j-bellocq-the-last-days-of-ernest-j-bellocq.html

[12] Jackson C, 2002, “Storyville Portraits”, Exhibition Abstract, The Photographers’ Gallery, https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibition/e-j-bellocq-storyville-portraits

Pingback: Assignment One: The non-familiar | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: 2) Project 1: The Unaware | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog