“The portrait is a sign whose purpose is both the description of an individual and an inscription of social identity”

Tagg, J, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (1988), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press P37.

We are presented with this quotation by John Tagg at the start of this project with the question of the difference between ‘description of an individual’ and ‘inscription of social identity’. On the face of it, the difference appears simple enough; a description being a representation of the subject and an inscription being more of a narrative of the age, culture etc. Representation though has been a fluid concept throughout Level 1 of this course. We already know that the artist and the sitter influence what is ‘represented’ in a portrait, which has been true for centuries. Take the example of the famous portrait painter Hans Holbein, who painted English monarchy during the Tudor era. Holbein’s representations of his subjects were often defined by the need for a narrative about the person’s status or social standing during a time where many people in England had never actually seen them. The portraits needed to convey a persona for the public. which was largely based on how they should be seen. His most controversial work was undoubtedly that of Anne of Cleves (below) which was commissioned by King Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell in 1539. Holbien was to capture Anne’s likeness as part of a petition by Cromwell for Henry to marry her. Holbein duly completed the painting which depicts a pretty young woman in a regal pose.

When Henry actually met Anne, he was said to be less than impressed with her in part because she did not resemble her likeness. The deception is widely believed to be what led to Cromwell falling out of favour with the King and ultimately his execution. Holbein is remembered in history for this glaring error of judgement, although it is unlikely that the painting alone was responsible for the problems with the Queen that followed him painting it. Holbein though is shown to be pushing the boundaries of ‘representation’ with this painting.

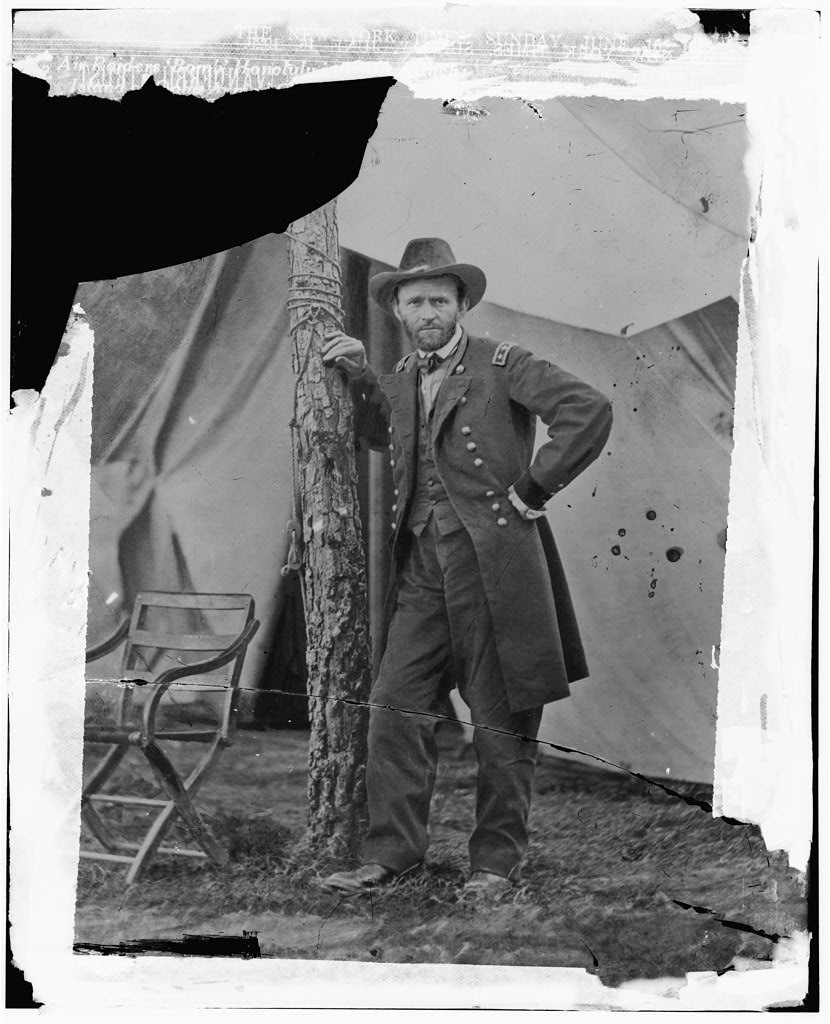

The same representation can be seen in the early photographic portraits, which is not really surprise owing to the staged nature of the medium in its early days [2]. As photography was less time consuming (and presumably less expensive) than painting, subjects could more readily appear in many portraits over a period of time. Take the following examples of early portraits of Ulysses S Grant, who became the 18th President of the United States after leading the Union army to victory in the American Civil War. Grant had portraits made both using traditional painting and with photography and it’s the latter that I found to be most interesting.

In this photograph, Gen. Grant is shown standing in what looks like a tent, leaning against a tree that forms part of the structure. He is shown in his military uniform, but he is represented as a soldier whose stance gives the impression of a man taking a moment from the battle. As the location for the photograph is Grant’s headquarters at the battle of Cold Harbor, VA, it’s reasonable to assume some accuracy to the way he is being depicted. However, we know the photograph would have required some time to set and shoot, so the scene is very deliberately staged. Grant’s expression and pose suggest a relaxed, confident and solitary commander, with the only other element that is present in the image being a chair presumed to belong to him. The intensity of this image is impressive for the time because of how long the pose would have needed to be held for, while it’s contextual simplicity represents what the American people would have associated with the leaders of the two armies (the opposing leader General Robert E Lee was pictured in similar photographs).

The second image (below) shows Grant as the 18th President, taken some time between 1870 and 1880.

Here we see a very different man from the previous image that was taken probably only a decade before. Grant is now pictured in a formal suit in a pose that represents him as the leader of the country. Grant’s expression still shows the confident leader as before, but the formality of the image and complete lack of any other context reminds me of the professional profile pictures that are commonplace in the current digital age.

What these two portraits show is the public image of one of the United States’ most celebrated military and political leaders. Although they show very different men despite the short period of time between the dates they were taken, neither picture describes what happened to Grant in that period. The point being made by Jenkins in Re-thinking History (1991) is reinforced by these two images:

“We should distinguish between the two by calling ‘the past’ everything that has happened before and calling ‘historiography’ everything that has been written about the past”

Jenkins K, Re-thinking History (1991) London: Routledge. Pg.7.

The first image was seen as ‘the past’ when the second was taken, but it says nothing about the war, the losses or strategic decisions that the great general made, merely that he was there. Historical texts and reflection by the American people, leading to his election as President, provide the historiography that Jenkins refers to. The photographs support the narratives rather than create them by themselves. With the advent of the automated portrait that was used for formal identification of an individual, portraiture itself took on a different meaning. The images made no reference to social identity, financial status or public persona. Arguably, the creation of formal portraits of a person could, if assembled together, tell the story of someone’s change in appearance throughout their life, but little else would be gained from them beyond that. However, the advent of the selfie in the 21st Century provides much more contextual information about a person than before. Modern portraiture is much more accessible by all parts of society, which for me helps create that sense of identity within and between social groups.

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815 to 79)

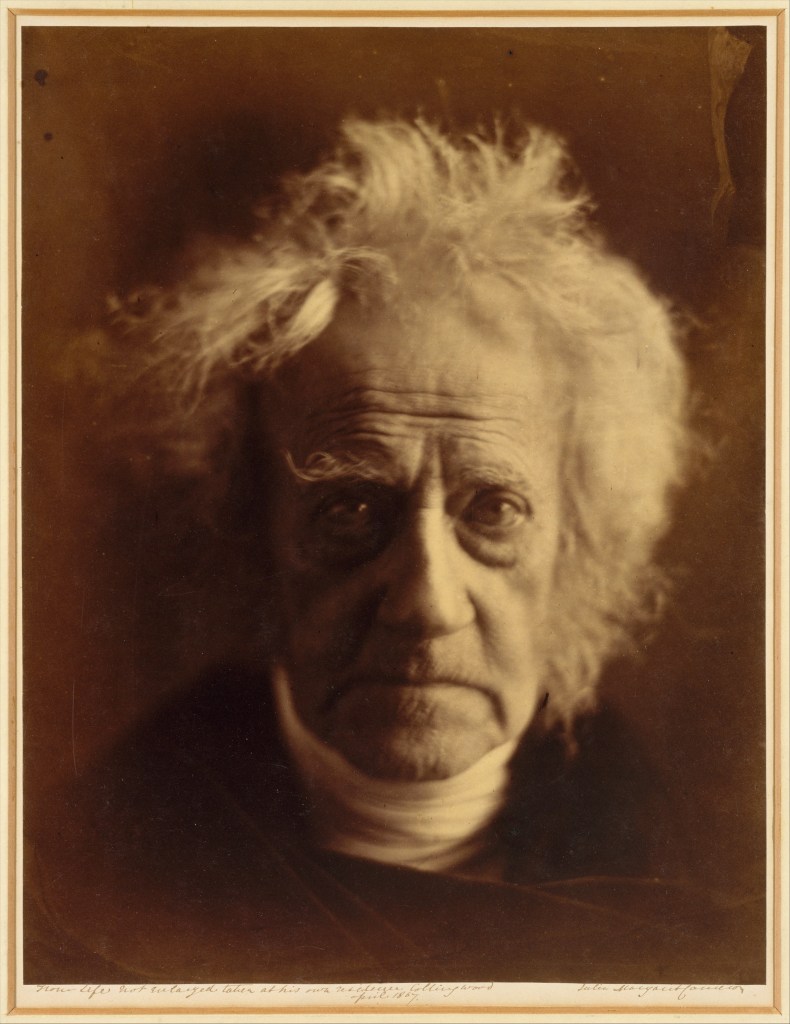

One of the most innovative portrait photographers of the 19th Century, Julia Margaret Cameron sought to move away from the formal, scientific approach to portraiture that had been the norm since the medium was invented. Where other photographers made their portraits full or half length pictures of their subjects, including contextual references to represent them in a particular way, Cameron took a different approach. Her portraits were much more close-up in composition and used high contrast between highlight and shadow to increase the drama of her subject’s appearance. She also challenged the convention of sharp focus and long depth of field which made her pictures ethereal in appearance. After receiving significant criticism from the her contemporaries for this, she asked her friend Sir John Herschal:

“What is focus and who has the right to say what focus is the legitimate focus?”

Julia Margaret Cameron

Herschal was a famous astronomer so one would have expected him to have taken a similar view to the photographers who had criticised her. However, Hershal like many of the famous friends that Cameron had photographed, was a fan of what she was trying to do. One of her portraits of him took his profession as an eminent astronomer and portrayed him as how she saw him; as ‘teacher and high priest'[5].

Sir John Herschal by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815 to 1879)[6]

The portrait shows Herschal in extreme close-up with his wild hair lit to create an ethereal corona around his face. His piercing gaze points to his inquisitiveness and intellect. Cameron was using photography, in particular portraiture, to create art rather than scientific record. In her tableaux creations, her female characters often took on the appearance of the angelic, with pale, flawless skin lit in a way to make them almost unreal. Her male characters by contrast were lit in a way that highlighted the lines of their faces, their frowns and expressions that alluded to the learned men, often influenced by priests or prophets.

Tracing Echoes – Nicky Bird (2001)

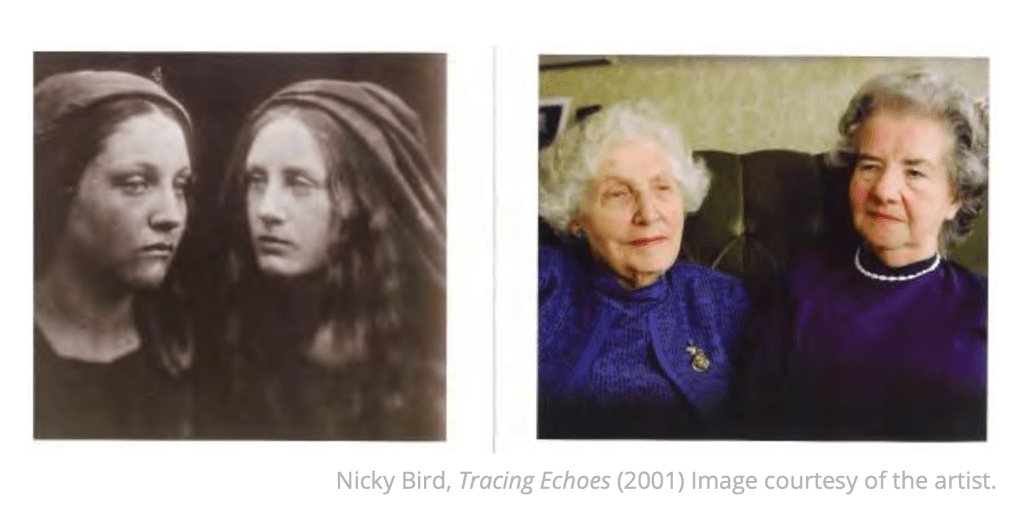

I first came across Nicky Bird’s work during Context and Narrative where the artist had curated a collection of unwanted photographs that she had purchased on eBay [7]. In that work, Bird was creating narratives with the available information from the seller that gave the collected photographs new purpose. The act of creating an archive and her subsequent sale of the photographs highlighted the transient nature of history with their new owners adding to the story by purchasing what was once unwanted. I found Bird’s connections between the past and present fascinating, so when I started looking at Tracing Echoes I could see a similar theme running through the work. Bird’s work in this project isn’t limited to historical portraiture as the basis for it came from Bird’s time as artist in residence at Cameron’s home, Dimbola Lodge. It’s her portraiture that relevant to this course though and in the case of Tracing Echoes, Bird connected the past and present by shooting similar photographs of the descendants of Cameron’s subjects. When I look at these images and the accompanying text, I can see the clear connections between past and present. However, I get more of a sense of mimicry than I was expecting. The photographs that are included in the notes, for example (below) show the the shots by both artists side-by-side.

Bird has selected a similar ‘facing’ pose for her two women but hasn’t used the same technical approach to the shots (background composition and lighting) as Cameron. Instead, her portraits look more natural than Cameron’s and because of the clear differences in the photographic technology in the intervening 130 years set Bird’s portraits very much in the present. We are presented with two elderly women without any other real context beyond their relationship to Cameron’s original subjects. My issue with Bird’s photograph is that it the passive expressions of her subjects look forced to me. It’s as though in asking her subjects to pose in a similar fashion to Cameron’s photograph, the result is something that doesn’t appear genuine. I really admire Bird’s work in exploring history and as such, Tracing Echoes is an important natural extension to Cameron’s story, which was so tragically cut short after a career of just 11 years [8]. However, as a celebration of Cameron’s innovative style, I don’t think it works – perhaps that wasn’t really Bird’s objective but it’s less impactful as I would have hoped.

Emil Otto Hoppé (1878-1972)

I admit to having never heard of Hoppé’s work until reading about him for this project. The story of what happened to his work underlines the points made by Tagg and Jenkins earlier in the notes with regard to representation and historiography. Although Hoppé was well known during his lifetime, his portraiture was not because of the decision to sell his catalogue to the Mansell Collection, a commercial picture house in London. The Mansell Collection was an early version of what we know now as a commercial picture library such as Shutterstock or Getty Images. In collecting the works of well known photographers, the Mansell Collection ensured that there was a rich variety for potential commercial use, but this was counterproductive in terms of art. The images were archived by subject rather than artist, which had two effects. The first was that the identifying factor for an image was what the subject was. In the case of portraiture, the picture literally represented a specific subject, e.g woman or child etc. rather than any other context included by the artist. It’s possible that the collection applied other references in its archiving decisions, but the effect was that the pictures were pigeonholed into certain categories. The second effect was the more damaging in that by assembling the collection in this way, Hoppé’s work was not curated as a collection in its own right. Therefore, anyone reviewing the available portraits in the Mansell Collection would not know the extent of his work. What made the latter effect worse was that the collection was not available to the public or any critics or historians for many years. To Jenkins’ point, this prevented any historiographical narratives to be created from the work and as such Hoppe’s portraits did not stand as historical documents.

When his portraiture work was eventually discovered, it confirmed his reputation as a master photographer. An example can be seen below:

In this shot of Austrian dancer and actress Tilly Losch, we see some similarities with the style that Cameron pioneered many decades before. Losch is pictured in extreme closeup and in soft focus, which creates an almost supernatural feel to the picture. However Hoppé’s use of light and the model’s expression is what leaps out of this image. Strong catchlights in her eyes draw the viewer to look straight into them and because of the tightness to the composition, we cannot help but look from one eye to the other as if in direct contact with her personality. The light picks up her flawless skin and the angle draws attention to her striking features. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this photograph is what it doesn’t show. While Losch was a dancer, she was famous for her intricate and intense The Hand Dance, created 1930-33. The Hand Dance was obviously performed with Losch’s hands and one surviving film of her performance by Norman Bel Geddes [10] shows how little attention was on Losch’s facial features. Nevertheless, Hoppé’s portrait reveals to us her intense personality without showing her hands at all. For me, Hoppé’s seemingly simple technique achieves a great deal in representing Losch without any obvious nods to her profession as an artist.

Conclusion

This project has introduced the concept of portraiture as representation but not historical documentary without historiography, that is the additional context that history provides. As photography evolved as a technical discipline, the prophecy by Delaroche did not come true as such. Instead photography became a complimentary technique for portraiture with the pioneering work of early artists such as Cameron. Her approach of using photography to create caricatures of her subjects was definitely disruptive, with the technical establishment dismissing her both as a woman in a man’s world and as a practitioner of what they saw as science rather than art. When we look at Cameron’s portraits of famous sitters, we can draw our own conclusions about the representation but we need to consider the historiography in order for the images to say anything about historical context. The way that representation changes can be seen in the work of Hoppé with he unfortunate way that it was kept from the public and academia as well as being fragmented by categorisation. Curating his work affected the way people saw his portraiture and provided the ability to create the all-important social narratives that accompany them.

References

[1] Abrahams S, 2013, “Holbein’s Anne of Cleves (c.1539)”, Image Resource, EPPH website, https://www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/article/holbeins_anne_of_cleves_c.1533

[2] Fletcher R, 2021, “On Delaroche, Analogue and Digital”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2021/02/19/on-delaroche-analogue-and-digital/

[3] Fowx, E. G., photographer. (1864) Gen. U.S. Grant at his Cold Harbor, Va., headquarters. United States, 1864. [June] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018667429/.

[4] Brady M, 1870 to 1880, “Ulysses S Grant, 18th President of the United States”, Image Resource, The White House website, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/ulysses-s-grant/

[5] Mickich T, 2020, “Online preview of Dimbola’s Julia Margaret Cameron: Close Up exhibition”, Dimbola Lodge Museum, https://onthewight.com/watch-online-preview-of-dimbolas-julia-margaret-cameron-close-up-exhibition/

[6] Daniel, Malcolm. “Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/camr/hd_camr.htm (October 2004)

[7] Fletcher R, 2020, “Project 2 -The Archive”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/12/20/project-2-the-archive/

[8] SFMOMA, 2017, “Pictures from a glass house: Julia Margaret Cameron’s portraits”, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art website, https://www.sfmoma.org/watch/pictures-glass-house-julia-margaret-camerons-portraits/

[9] Unknown, 2011, “Hoppé Portraits: Society, Studio and Street”, Image Resource, The National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/hoppe/exhibition.html

[10] Bel Geddes N, 1933, “Dance of her Hands, Tilly Losch (1930-1933)”, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_dOSfEnKJo

Pingback: 1) Project 3 – Portraiture and the Archive | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: Assignment 4 – Image and Text | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: Reflecting on Identity and Place | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog