“From today, painting is dead!”

Paul Delaroche, c1840.

In the introduction to Part 1, we are introduced to the quote that is often attributed to French painter Paul Delaroche sometime in the early 1840s. He had apparently seen an early Daguerreotype image and declared that photography spelled the end for portrait painting from that day forward. Dageurre had invented and developed what is considered the first publicly available photographic process that would preserve the image observed by a camera. While it definitely turned the ancient phenomenon of the camera obscura, which had been around for centuries previously [1] into a practical application, it was certainly not the end of portrait painting as Delaroche predicted. Instead photography continued to evolve along a more scientific route than perhaps Delaroche was aware. The very first photograph was taken in 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce [2], an inventor whose fascination with the art of lithography led him to experiment with ways of improving his skills in creating these intricate artworks. Realising that he lacked the precision of technique to be any good, Niépce experimented with photosensitive materials and methods for fixing the image onto a pewter plate, some 14 years before Dageurre unveiled his process. Niépce started to work with Dageurre before his death in 1833, undoubtedly inspiring the latter’s eventual development of a stable process and ultimately himself being acknowledged as the inventor of photography. Deguerre himself wasn’t an artist either, but a chemist who like many, was interested in the science behind preserving an image as a recording. During this time, an English inventor called Henry Fox Talbot was also working on preserving the photographic image, but on paper instead of the polished metal used by Dageurre. Fox Talbot’s work was the basis for future evolution of photographic film and papers. In Fox Talbot’s case, he was interested in creating accurate pictures of flora and fauna, but lacked the skill to draw his subjects. He, like Niépce was trying to make up for the lack of artistic skill with the use of science to create faithful reproductions.

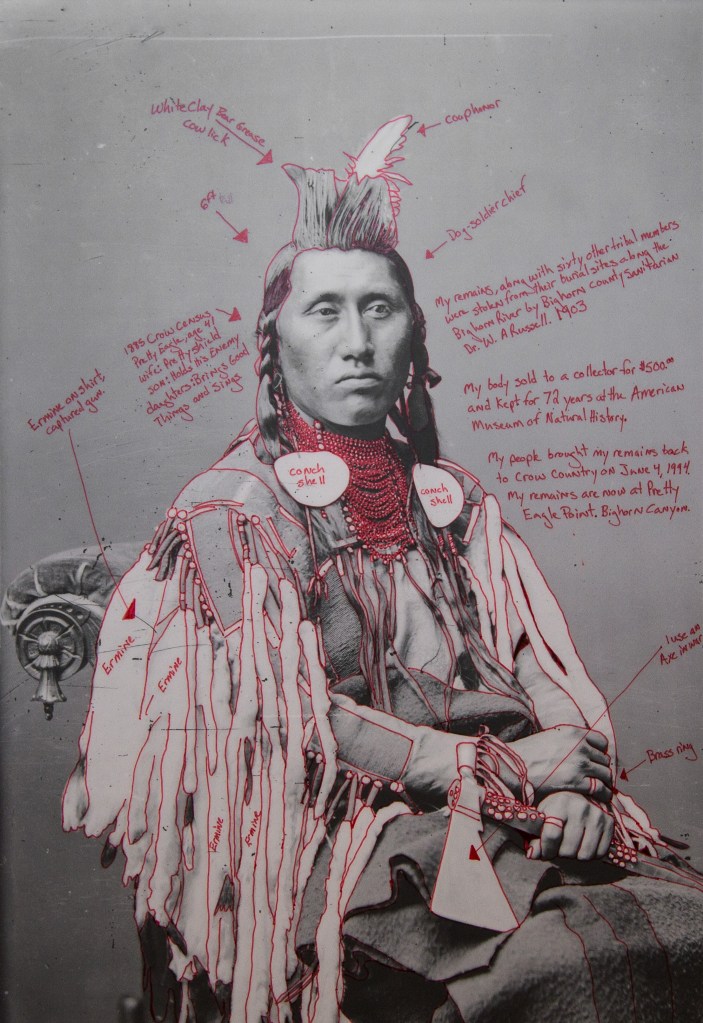

It stands to reason that when Delaroche first saw this new technology used for traditional portraiture, he would have thought it was going to make painting redundant. The early portraits by Dageurre although fairly primitive, must have looked like a more faithful representation than was possible by the portrait painters of the time. As the notes indicate, in actual fact the balance between traditional and new took a while to establish itself and painting as art remained popular way of representing a portraiture subject. When we look at the early portraits made using photography, we see the technique more the focus than the subject. Early photographs required long exposures for the process to work, so subjects needed to sit perfectly still for the picture to be sharp. Any real creativity was limited to the use of costume and background, which was often just whatever was contemporary. These photographs were highly constructed and any suggestion of personality came from the subject rather than the photographer. In Context and Narrative, I looked at the work of Wendy Red Star [3] who incorporated photographs of tribal elders of the indigenous Crow tribe (her ancestors) who were invited to Washington in a farcical summit which resulted in them having their lands taken by the modern American government. The photographs were staged by a famous photographer of the age who had a reputation for taking cold, distant portraits. It was believed that this way of representing the elders would show the people of Washington how alien they were to the emerging culture of the US. What resulted though was a series of images that achieved the opposite. Instead of distant and uninteresting, the elders appear proud, dignified and complex (owing in part to their full traditional dress).

Portraiture using photography differed from traditional painting in that the subject had more control over the finished piece. When we think about what Delaroche was famous for, we can see that painting still had its place in creating art that was flattering, or fantastical. Delaroche’s fascination with depicting the historical executions of key figures in history, his most famous being The Execution of Lady Jane Grey [4], is an example of the fantastical representations that were possible through the imagination and skill of a painter.

This particular tableau painting was derived from the many accounts of the execution but Delaroche placed the scene in an elaborate indoor setting that looks more like a church than a scaffold. In reality, Grey’s execution took place outside in the Tower of London grounds with a small crowd in attendance. With this artistic licence Delaroche is perhaps saying that the tragic killing of a teenage girl, who is now recognised as a manipulated innocent in the political instability of Tudor England, was akin to taking the life of an angel before the judgement of God. Whatever his motivation, Delaroche wasn’t present at the execution so could play with the aesthetics and details as much as he liked. The same couldn’t be said for photography until the subsequent development of the materials, equipments and techniques that allowed for the photographer to be more creative.

A modern equivalent of painting vs. photography can be seen in the advances of digital technology, which is present in every genre including portraiture. The notes refer to how photographers and the general public moved away from traditional film to digital imaging, which is a discussion that is often found in social media groups. As a film shooter, my view is that the advances in digital are not having the same impact as those that Delaroche was worried about. In his case, accurate reproductions created by the camera required a different set of skills that in some ways rivalled the painters of the age. Skills were still needed though, as photography was a complex technical process involving mechanical tools and chemistry. Painting still had the edge in terms of creativity and artistic licence, but developments in cameras, films, lighting and processing techniques addressed some of those shortfalls. With the latest advances, I would argue that the skill has almost been eliminated from portraiture with the rise of the selfie. People can now shoot portraits and rely on electronics and software to be creative to a point. No other photographic skills are required until the shooter wants to take more control. I was discussing this phenomenon with a fellow photographer and teacher who at one point decried the use of mobile phones with onboard processing and is now, because of demand, teaching mobile phone photography as part of his business. This also perhaps explains the resurgence in analogue film , where novel and expired film emulsions are making people who are new to photography want to experiment with different aesthetics. I recently met someone who has discovered film by buying point and shoot film cameras in junk shops and shooting expired film in them. His images take on a totally different meaning because of the way the film reacts to the light, even thought his candid portraits are similar to many other contemporaries.

Conclusion

I was interested in the introductory statement in the course notes so decided to dig a little deeper. I was glad to have done so as the evolution of photography, with all of its perceived truthfulness and accuracy, has not destroyed other art forms as feared by Delaroche, but instead been an enabler for them to be regarded for what they are. For example, the Royal Family still commissions painted portraits regularly as well as photographs. The former continues a traditional portrayal of them that complements historical representations while ‘telling a story’ to tie in with the contemporary view of them. The photographs create a different narrative; one of normality and relatability that also showcases the artist as much as the subject. People still enjoy both forms of portraiture in equal measure. As the talkshow and car enthusiast Jay Leno once said of the evolution of the automobile,

“Back then, horses were the primary means of motive power, pulling heavy carts and carrying people. Sadly, they would drop dead in the streets from sheer exhaustion or abuse. And mounds of manure befouled Chicago, New York and other big cities, spreading nasty diseases like dysentery. Suddenly, the automobile came along and people said, “Oh look, there’s just a little blue smoke! How nice.” Soon, horses were no longer misused as draft animals and the amount of droppings lying around was significantly reduced. Everyone was happy.”

Jay Leno, talking about the evolution of the car

People still enjoy cars and horses but for different reasons, the latter being recreational instead of industrial. My view of the evolution of portrait photography is that it serves a different purpose analogous to painting but it was never going to replace it.

References

[1] Unknown, 2021, “Camera Obscura History – Who Invented the Camera obscura?”, Photography History Facts Website, http://www.photographyhistoryfacts.com/photography-development-history/camera-obscura-history/

[2]Unknown, “The Niepce Heliograph”, Image Resource, Harry Ransom Center, https://www.hrc.utexas.edu/niepce-heliograph/

[3] Fletcher R, 2020, “Post Assignment 4 Feedback”, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/12/04/post-assignment-4-feedback/

[4] Delaroche P, 1833, “The Execution of Lady Jane Grey 1833 Oil on canvas, 246 × 297 cm Bequeathed by the Second Lord Cheylesmore, 1902 NG1909”, The National Gallery, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG1909

Pingback: 1) Project 1: Historical photographic portraiture | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog