Introduction

In this project we are introduced to how artists use archived material as the basis for their work, whether creating their own or challenging the concept. Like the other artists in Part 5, they are using other media as the inspiration for their version of reality. Here we will look at two approaches, one that takes a view of material through the way that people engage with an archive and one that seeks to build order from seemingly unconnected material.

Broomberg and Chanarin

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin were invited by Belfast Exposed, an organisation that manages an archive of photographs taken by photojournalists during The Troubles, to create a response to it. Their approach was to first look at how an archive works, from the selection of images to the way that people interact with them. The Belfast Exposed archive contained over 1.8 million photographs arranged as contact sheet prints stored with their negatives. During the many years that the archive has been curated, it has been maintained by a group of archivists working within the constructs of the local authorities as well as in terms of what the public are allowed to see. The artists started by looking at the contact sheets as articles their own right rather than the photographs within them. The evidence of the many years curating, cataloguing and even censoring the images was evident by markings on the sheets; many techniques were used from hand annotation to the use of stickers and sticky notes. What the artists realised was that these annotations were only made on the printed sheets and the negatives remained untouched in the accompanying files. This was brought home to them when they looked at the damage caused by the visiting public. In some cases, those who appeared in the photographs objected to being in the images and scratched themselves from the contact sheets. In a video presentation of the work [1], the artists realised in both cases, some were using the archive to hide part of the story from the viewing public, whether out of shame or personal embarrassment. What the artists also became drawn to was the use of coloured round dots on the contact sheets that were used to obscure particular elements in the pictures that gave some concern to the archivists. Far from being the straight documentary that we were introduced to earlier in the course, these edited images only revealed part of any story that the original photojournalists observed. In removing the dots, the artists could see what was being hidden. The archive had become more of a document of what wasn’t in the photographs as much as what was included. In the presentation[1] the artists discuss the concept of responding to what is considered to be an accurate historical document. The Troubles in Northern Ireland were a brutal time of protest and suffering which the archive intended to document. However, in censoring some of the images, such as the behaviour of some of the law enforcement agencies at the time, the archive offers a particular narrative. In their response the archive, Broomberg and Chanarin invert the notion of documentary. Their approach for their first series was to use a circular mask in the darkroom which could be positioned when reproducing the original photograph (from the untouched negative).

For their second series, they reproduced the obscuration seen on the original contact sheets in larger prints.

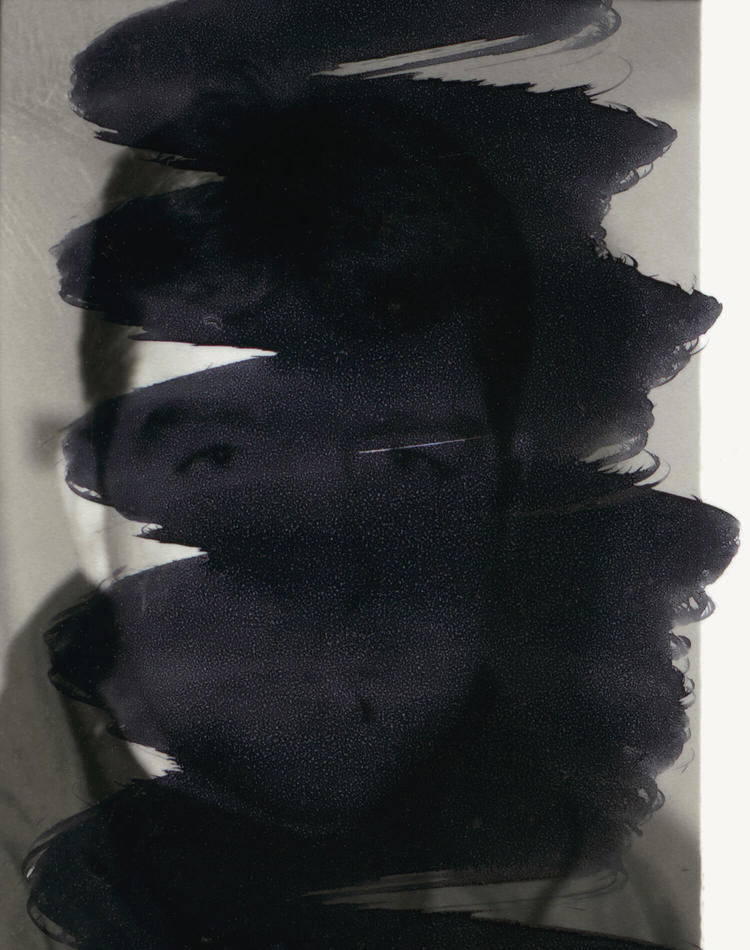

Both series are curated in a way that tell a different story of The Troubles to the archive. The story is now more a fiction than a series of ‘facts’ that the artists took control of. Now the people of Northern Ireland are seen almost out of their historical context, which means that the viewer can only bring what they know about the conflict to the pictures. In the first image above, the two girls are shielding their faces from being photographed. We are left wondering why this might be because we cannot see what else is happening in the picture. The artists are showing us something previously obscured and out of context. This photograph could be anywhere and in any time period; the artists have elevated the girls from The Troubles and are asking use to think what they might be doing or involved with. In the second image, we see a man whose face has been obscured with a black marker. The immediate thought when I look at this image is that the obscuration reminds me of the classic redaction used in official documents that are somehow classified. Whoever did this was trying to keep the man’s identity from us but as we look closer, hasn’t been completely successful. Who was the man and why didn’t he want to be identified (assuming he was the culprit for the redaction)? Was it out of embarrassment, concern for his privacy or perhaps fear for his life. If we apply no external context, it could be any of these reasons and more, but if we consider against the context of the situation in Northern Ireland, it could well be the out of fear. In both images, the point about their elevation from the context of the archive is further emphasised by the factual titles that the pictures are given. The titles make no reference to any history, merely point out the obvious subject in the frame.

Nicky Bird

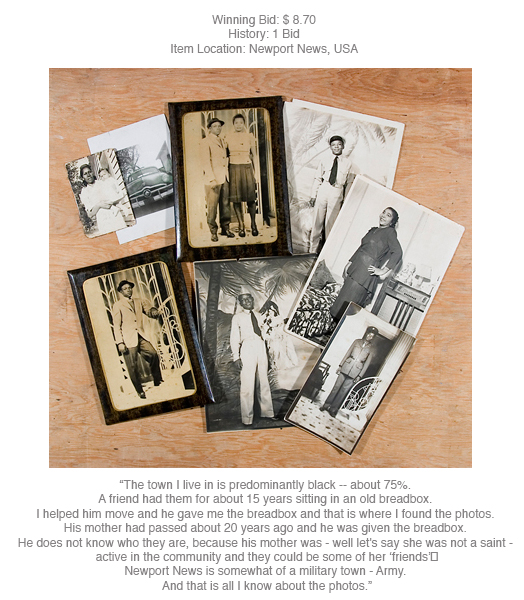

Nicky Bird’s take on the archive is slightly different to Broomberg and Chanarin, but the end result is similar. We are told in the notes that Bird purchased photographs from eBay that nobody was interested in. They images of people and families had found their way onto the auction website with the obvious sentiment that they were unwanted. Immediately this idea of people discarding a family history provokes a response in the viewer; what has happened to make the seller reach this conclusion? Is there some historical reason or is it merely a clear-out? Are the people in the photographs even related in any way to the seller? I know from experience that the resurgence of film photography has created a demand for old cameras that have been lurking in people’s attics etc (I have purchased many of my collection this way). Sometimes, these cameras contain partially used film and sometimes they are kept with negatives that were shot by the owner. This phenomenon of ‘found film’ has led to many images that have remained unseen for decades being viewed for the first time. They are out of their own time and being viewed in the context of the present. What Bird did with her purchases was to ask the seller how they got hold of them and whether they knew anything of their history. The answers were included by Bird along with details of the purchase as context for the collections of photographs. This approach, similar to diCorcia’s Hustlers (where the men’s names and their fees were included) is very factual and its impact entirely dependent on the granularity of the information provided by the seller.

We can see from the photographs in the collection above that there is an intimacy to them. When we read the notes from the seller, the photographs take on a greater sense of emotion which, coupled with where they eventually ended up (on eBay) asks the viewer to evaluate their response to them. Bird explored the way that people connect with historical photographs during an interview with Sharon Boothroyd[5]

eBay is interesting as a sort of house clearance – in one way the photos can be seen as thrown away, but in another sense, it is a type of postponement i.e. why do people not just throw these photos in the bin? In fact, one eBay seller had rescued a batch of photographs from a skip, while another said that eBay sellers and buyers were new ‘custodians now’ for such materials… so it was interesting that both examples (the brutal and the benign) had a presence in Question for Seller.

Nicky Bird[5]

With the idea that Bird was the new custodian of the images, we now see how her role as archivist has evolved. In curating a collection of groups of images in a a disparate collection, the archive that she creates is one that both preserves the history, but allows us to write our own stories based on the subjects themselves and the journeys the photographs themselves have taken towards being viewed.

Bird held her own auction of some of the photographs in her work for charity, which in a sense passes the historical preservation and maintaining of their impact on to the next generation of custodians. In doing so, Bird’s archive is transient; the opposite of our understanding of the traditional definition. Like Broomberg and Chanarin, the artist takes control of how people will interact with it, fabricating reality and suggesting new meanings as she goes.

References

[1] London Consortium TV, “Broomberg and Chanarin: Presenting Four Projects on Vimeo”, Vimeo online, https://vimeo.com/32622798

[2] Broomberg and Chanarin, 2015, Tate Installation Photographs, artist website http://www.broombergchanarin.com/hometest#/contacts/

[3] Aikens N, 2011, “Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin – Paradise Row”, Review, Frieze, https://www.frieze.com/article/adam-broomberg-and-oliver-chanarin

[4] Bird N, 2006, “Questions for the Seller”, artist website, https://nickybird.com/projects/question-for-seller-2/

[5] Boothroyd S, 2013, “Nicky Bird by Sharon Boothroyd”, Photoparley website, https://photoparley.wordpress.com/2013/05/09/nicky-bird/#comments

Pingback: 5) Exercise 2: Re-situated Art | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: Post Assignment 5 Feedback | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog

Pingback: 1) Project 1: Historical photographic portraiture | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog