Introduction

This paper is in response to the work on Derrida and deconstruction, where a cultural text can be essentially broken down into multiple contextual elements with supporting and contradictory narratives that can be drawn from them. Derrida considered language to be a flawed way of communicating, asserting that as language was a human creation it was no surprise that it would include inherent biases and perspectives that steer the reader or viewer to a particular conclusion. With the idea that the visual arts can also be treated as a language, we are reintroduced to Barthes and his work on semiotics. Semiotics are the signs within language that can be used to make up meaning. When I first looked at the supporting notes for Semiotics, I was immediately struck by the ‘logical’ nature of the expressions which in the cases of Signs, Signifier and Signified look more like equations than anything to do with art. Of course, the labels that Barthes is applying to contextual elements and meanings are, in a way trying to apply some sense of reasoning to the critique of a photograph.

The Semiotics

We are given the simple descriptions of the semiotic terms that Barthes postulated in the notes[1], which are:

Sign: the overall effect of the phtograph

Signifier: the actual picture in terms of its formal and conceptual elements

Signified: what we think when we look at the picture

The Sign is expressed as the sum of the other two, which esesstially combines the formal visual with the viewer’s reaction to the image. This makes sense as the sign is the impact of the image not the viewer.

Denotation: the objective translation of the image – what does it contain?

Connotation: the interpretation of the elements, which can be widely variable depending on how we see them.

We use these expressions in the English language regularly when we are trying to describe the purpose of meaning of something, e.g. “this symbol denotes the status of the equipment” and “that decision has multiple connotations”. As a former engineer turned manager, I observe these expressions in common use respectively as the former works more in absolutes than the latter.

Studium: the general status quo of the image. The undying cultural, political or social meaning which is derived from most of its contextual elements.

Punctum: an element that disrupts or contradicts the Studium.

These two are driven more by the viewer’s own perception of culture, their political leanings and is shaped by there personality. While the contradiction of the elements might be visually obvious, my initial thoughts on how they are interpreted by the viewer will be more or less impacted by how strongly they feel about them.

Intertextuality: the final factor in viewing photographs being what the viewer brings to it. Like Studium and Punctum, the life experiences of the viewer will affect how they read the image. For me, this fits neatly with the ideas from Death of the Author [2] where Barthes incites the viewer or reader to take a bigger part in the narrative of the image or text, rather than trying to seek out what the artist intended. Intertextuality then, is the core of the our reaction to something we see that distinguishes our feelings or opinions from those of others.

Practical Example of Semiotics

In looking at each of the semiotics and how they are found in an image, I elected to choose a photograph to examine. The photograph is by one of my favourite photographers Joel Meyerowitz, whom I’ve discussed previously on this course. Meyerowitz was one of the early pioneers of using colour film for street photography, arguing that colour is more representative of how we see the world as well as suggesting that instead of a distraction, it could be used to add to the subject. The image I chose is shown below.

Starting with the signifiers, the image is of a street with buildings, people and cars at either dawn or dusk. Two people dressed in large shoe costumes are walking way from the camera, while a woman on crutches is walking toward them,. She has her clearly injured leg raised, pointed at one of the shoes and a smile on her face. Another man is see heading in the same direction as the shoes.

The signified for me is the humorous way the woman is pointing her foot at one of the large shoes. The reaction on her face suggests that she finds the encounter with the costumed people to be funny, presenting her injury for them to look at in an almost absurd way.

The sign for me is an absurd encounter with some people wearing large shoe costumes with a humorous play on the contrast between the characters.

In terms of denotation, the objective meaning of the image is fairly simple. Here are two people either going to a party or taking part in some form of advertising, walking down a city street. Their encounter with an injured woman causes an interaction which is observed from Meyerowitz’ perspective. We cannot see the face of the ‘shoe’ she is interacting with, but given the smile on her face it is reasonable to assume that it’s a cheerful one. The exaggeration of her walking style looks to be fun or with some level of mimicry which could be the reason for the jovial expression on her face. The other actors in the scene (the cars and the other pedestrian) are heading in the same direction as the shoes.

It’s when we consider the connotations of the elements described above that we start to deconstruct the image. The ‘shoes’, pedestrian and cars are all facing the same way toward the light at the end of the street. The use of leading lines in the composition suggests that the journey these actors are on is a long one. The scale of the shoes could be interpreted as everyone’s shoes and the way that they positioned could mean that everyone is heading down the street. The woman is the only element in the frame that is heading in the opposite direction, which could be interpreted as rebellion or some form of struggle against the tide; her injury gives weight to the latter. The humour that was signified in the first viewing of the image could be irony, with the smile being more sarcastic than genuine. The shoes take up a lot of the sidewalk, so perhaps the showing of her injury is an ironically angry gesture to get out of the way. What we cannot see in the image is the faces of the people wearing the shoes, which could be somehow dismissive of her presence. When we consider that there are no other faces in the other than the woman’s, we could interpret that as being that seemingly nobody caring about her or her predicament.

Now considering the studium, we see a city street in what looks like Manhattan in New York City. The connotations above when considered with the fact that Manhattan is considered to be an crowded place, create another narrative about the flow of people all heading in the same direction. The punctum is of course the woman who is defying the status quo by walking the other way. Her appearance and apparent disability offer a more sinister view of the big city and the struggles that some people have to fit into that society and culture. The photograph was shot in the 1970s, which has a naturally very different political feel to modern times.

The breakdown of the photograph offers multiple meanings which is what deconstruction and post-structuralism is all about. However, in terms of my interpretation, it is the intertextuality the largely defines how I react when I look at this picture. As I said, I am a fan of Meyerowitz and know that in terms of this picture he saw the amusement in the events unfolding in front of him. I’m also a huge fan of New York and it happens to be one of my favourite places to visit. Having these two personal connections means that I can only ever see this as a funny scene. New York is a place where anything or anyone out of the ordinary isn’t noticed or prejudiced against by the majority of the residents, so seeing two people wearing giant shoes wouldn’t have caused a stir. The woman’s reaction and her exaggerated walk is a celebration of that uniqueness for me and Meyerowitz’ perspective on street photography further strengthens my feelings when I see this picture:

“A lot of what I am looking for is a moment of astonishment,” he says. “Those moments of pure consciousness when you involuntarily inhale and say ‘Wow!’

Joel Meyerowitz

The Rhetoric of the Image – Panzani Advertisement

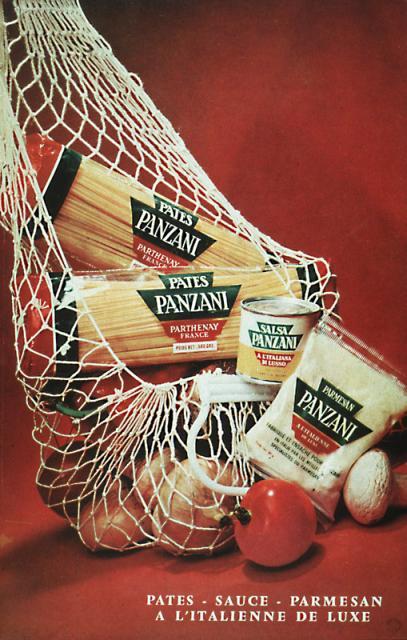

In his paper The Rhetoric of the Image [4], Barthes analysed an example of an image used in commercial advertising, specifically a printed advertisement for Panzani food products. In his treatment of this image, Barthes uncovered multiple signs (the overall meaning) and many signifieds within the frame that support them. His systematic breaking down of the image into it’s many potential meanings explains how we as viewers we are led to a conclusion based on ours or our culture’s visual references.

Barthes starts by pointing out the seemingly obvious element that we see when we look at the poster, the text both on the labels and in the caption. The use of the French language in the caption Barthes argues, is a coded sign about the way the product is Italian. This plays directly into our perception of other cultures in using a European language, the stereotypical idea of what being Italian is is emphasised and then further built by the labels on the food. The Panzani name drives home the message that these are Italian products for making Italian dishes.

In terms of the visual, Barthes discusses three further individual signs or meanings that the picture creates. The first is the way that the shopping bag is dropped on the table as if returning from a market or small shop. Barthes refers to the widespread cultural belief of shopping for groceries in this way being more natural than the alternative bulk buying context. The notion of naturally fresh comes with the way the produce is allowed to fall out of the bag, in contrast to the modern packed and refrigerated reality that most experience. The second sign that Barthes identifies is the use of the colours in the scene. The red, green and white themes in the image contour up the Italian flag, even though the products and colour pantones are all different. They are not even arranged as a flag, but the visual pointers along with the names on the labels drive home the sense of the food being Italian. A further sign is signified by the number of labels in the picture giving the impression that Panzani is a ‘one stop shop’ for Italian food. The final sign is the way the image speaks to still life, the signifier being the arrangement of the products and the way they are lit. This sign is more about not sending any cryptic messages about what the products are, merely that here they are for purchase. It’s no surprise that this sign is present as the picture is after all an advertisement. The more interesting point is that it’s probably not the first and most obvious of the signs. We instinctively know what an advertisement is, so only when looking at the image closely can we see the signifier that points to the classical still life paintings we are familiar with.

I found The Rhetoric of the Image an interesting paper to read. In breaking down the picture into the semiotic elements, Barthes changed the way that I looked at this seemingly uninteresting advertisement. The extract that I used for this post[] only dealt with signs, signifiers and signifieds, but Barthes goes on to consider the what the elements denote and connote and how our cultural viewpoints affect the reading of the image. I associate Italy and things Italian with the classical tourist impression of the country and its people. Flamboyant, brightly coloured fashions, exotic sports cars and glamour, as well as healthy food are all cultural references for me, so when I looked at the Panzani picture, I didn’t need the French caption to lead me to the conclusion that this weree good products. The thing that is interesting is that I have no evidence that beyond the tomatoes in the picture, the rest of the food is healthy or indeed any good. The visual signifiers and signifieds create those impressions in such as way as to my not wanting to question them. In his paper then, Barthes seeks to explain rather than contradict. His message lends itself to Derrida’s deconstruction idea that, that every element potentially has multiple meanings and traces of its opposite. In this case, the product looks Italian because the signs suggest so, but we also have the knowledge that we don’t know where Panzani products are manufactured. That and the many other distinctions leads us to challenge what we think we see in a photograph.

As an addendum to this, I recently revisited and completed Exercise 3 from Part 3 on Childhood Memories [5]. When I finished the work, I showed it to my wife and mother-in-law. I noticed something that I had not appreciated previously, that is the need to try to explain my photographs. I managed to stop myself from completely explaining the meaning of the image and instead observed their reaction to it. This is a key learning for me – whatever my intentions for a picture, how other people read it is dependent on my use of contextual elements and what they bring to the viewing.

References

[1] 2020, ‘Photography One – Context and Narrative Part 4, page 123, OCA Course Notes

[2] Barthes R, 1967, ‘The Death of the Author’, essay

[3] Meyerowitz J, ’35mm Color Street Photography’, Artist’s Website, https://www.joelmeyerowitz.com/street-photography

[4] Frieze C, ‘Excerpt from Rhetoric of the Image, Carnegie Mellon University Course, https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~cfrieze/courses/Barthes.pdf

[5] Fletcher R, 2020, ‘3) Exercise 3: Childhood Memories’, OCA Blog Post, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2020/10/18/3-exercise-3-childhood-memories/

Pingback: Research Task: Rhetoric of the Image | Richard Fletcher OCA Photography Blog