Considering the three viewpoints, Charity, Compassion Fatigue and Inside/Out

Martha Rosler

Rosler’s assertion that the use of photography by social-conscience photographers increased the gap between social classes is an interesting one. Her essay ‘The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems’ looks at the photographers who documented the Bowery slums during the Depression era. Her view was that the use of photography to highlight the plight of the poor and the homeless was considered an attempt to bring their world into that of the higher classes to affect change. While on the surface it looks like a noble effort, Rosler stated that the effect of pointing out that ‘you have much better lives than them’ merely galvanised the class structure. For me, the criticism of the sentiment is harsh. As with the work of the FSA, the intention was to effect change by ensuring that the wealthy did not forget the problems of the poorer classes. In the case of the photographers working for the Farm Security Administration, the scale of the geography involved could only really be reported through photographs as many of the upper classes were not centred in rural America. Was it pushing a socalist agenda? Undoubtedly so, but when considering the imagery in a non-photographic review, I admire what they were trying to do. Where I agree with Rosler is the exploitative nature of the work in the Bowery slums. Here the photographers were capturing images of people who had little in terms of voice or in some cases, even consciousness. Alcohol and drug abuse was rife at the time, so many of the subjects would not have even been aware of the context the photographers were looking for. Some may have not registered that they were being photographed at all. I immediately saw the connection with Mendel’s Dzhangal, where the people themselves didn’t want to be photographed. By using their possessions without them being part of the project, Mendel essentially avoids any counter discussion about the lives of the people at the camp. The other connection I drew was when people photograph wild cats. Most access to wild cats is via a zoo or rescue centre, where an animal has limited ability to be as it would in the wild. Like many photographers who have shot these sort of pictures, I have waited for long periods to capture what I think is the behaviour of the cats and what I want the people who view my photographs to see. In fact, if I really wanted to document a lion or tiger as it should be seen, I’d have to go on a safari. Here, the constraints of environment are removed which allows the subject to act entirely naturally. Friends who have shot in these conditions say that there are many more opportunities to observe the animals when not trying to control them. When I read Rosler’s paper, I concluded that the Bowery and the social circumstances were the constraints and the people were effectively being watched for certain patterns of behaviour. I concluded then that this use of documentary photography is exploitative, even if that wasn’t the original intention.

In terms of its ability to effect change, I believe that photography is a powerful addition to wider perspective, either written or spoken. The irony of the socially conscious image that seeks to change, is that the only way it becomes well known is for it to be distributed. Distribution usually involves some form of financial benefit, whether through purchase or enhanced exposure. With the advances in social media and camera technology, that benefit is more widely acquired, but for me the expectation of some form of altruism in return is a naïve one. With Lange’s famous image ‘Migrant Mother’, the subject complained that she never benefited from the success of the photograph despite the photographer having done so. I suppose the thought was that the impact of the work of the FSA would outweigh any royalties, but nevertheless Rosler’s theory that the divide between rich and poor increases, is validated by the apparent lack of support.

Over the decades, we have seen examples of imagery provoking action in people, from Live Aid to Climate Change. In some cases, the appeal is for help while others seek to shock. The sheer volume of photographs that are taken of a single subject is, in my view, having a greater impact because of the perception that they statistically support the argument. For example, the bombardment of the suffering of animals due to habitat loss through climate change, provokes a sensibility in many (particular in the UK, where people are considered animal lovers) that sparks people into action. This plays somewhat into Sontag’s argument about compassion fatigue, but it’s demonstrably successful with animal charities being among the most supported in the UK.

Susan Sontag

Compassion Fatigue is a feeling that I regularly get when viewing photographs. Last year, I visited Tate Britain to see Don McCullin’s major exhibition. The collection contained some 270 photographs spanning McCullin’s time as a war photographer. The imagery was naturally harrowing but because there was so much of it, I found myself beginning to look at the way the photographs were shot rather than at the subject itself. I had become disinterested in the horrors of the images and even applied the same disengaged fatigue to his lighter landscape work towards the end of the exhibition. I think the shock value of war photography starts by making the viewer feel like it’s something real to them, but as the number of images increases, the sensation moves to one of normalisation. With that normalisation comes a sense of ‘it’s not real to me’. In my experience during the McCullin exhibition, I found that my sense of empathy toward the subjects dulled with the increasing number of photographs, but also my ability to reset my perspective when it came to less harrowing imagery. McCullin’s landscape photographs of the flood water on the Somerset Levels in late 1990s were bleak in the way they were photographed. As the majority of the other work was war or conflict, my natural tendency was to see the destruction of the flood water, rather than the dramatic power of nature. Similar to Mendel’s images of people in flood water, there is both resignation in the expressions of the subjects as well as a sense of comfort in a few of them. How can we tell the difference in the photographer’s intention?

Abigail Solomon-Godeau

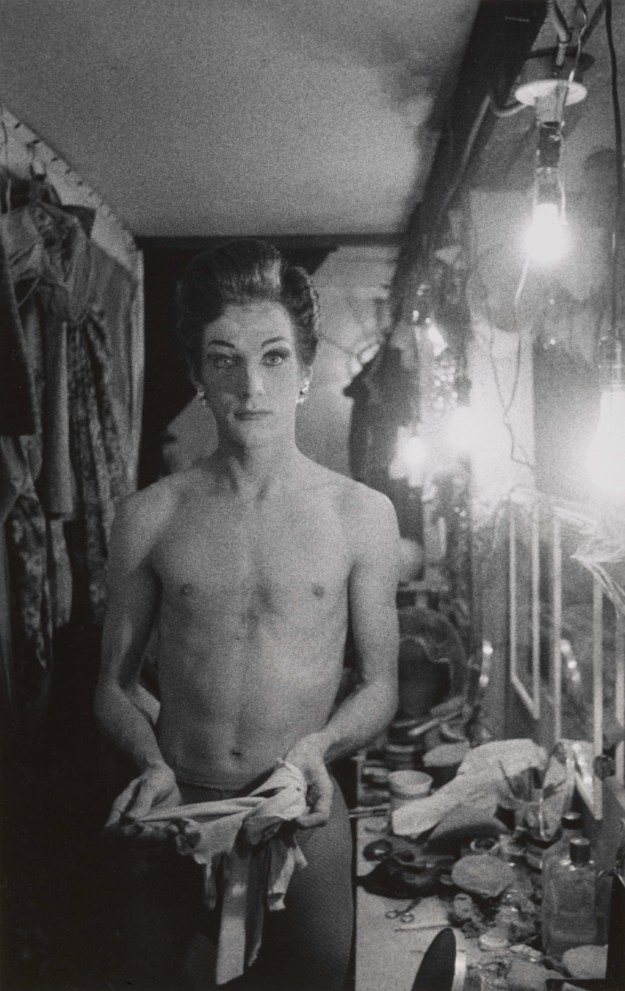

The answer to my last question comes from the essay by Abigail Solomon-Godeau. The concept of being an insider vs a spectator perhaps offers the explanation of the flood images. In Mendel’s images, the flood victims have let him into their lives to capture what are very clearly posed photographs. In the case of the photograph of the woman in her hallway that I described at the start of this course, the sense of being inside is even stronger because the photographer lives in the UK and is very much part of the society devastated by the weather of that time. In the case of his photographs from India, that connection is missing which for me turns him (and us) into the tourists described by Sontag. For me, then, the difference is around how we relate the image to our own lives or supporting context, in this case what we know about the artist’s body of work. During Expressing Your Vision, I looked at Nan Goldin’s work “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” that is referenced by Solomon-Godeau in her essay. My research took in a number of interviews with Goldin[1] where she talked about her years living in what others called the fringe society in New York. Her subjects often lived with her and as a consequence, Goldin’s photographs in that piece often show her friends in everyday relationship situations, some good and some bad. Goldin shows her subjects from a viewpoint of a clear closeness that can only really be achieved by being an insider. When I visited the Diane Arbus exhibition in London in spring 2019, I was struck by her early work photographing circus performers. As Sontag postulated, Arbus’ photographs were more of an impassioned look at her subjects and we really get that sense of ‘look at how different this person is?’ when we look a them. An example from each photographer can be seen below.

Female impersonator holding long gloves, Hempstead, L.I. by Diane Arbus, 1959 [2]

Jimmy Paulette on David’s Bike, NYC, by Nan Goldin, 1991 [3]

In terms of what makes a successful documentary project, I am left with the thought that it very much depends on what the photographer believes to be their viewing audience to be and the nature of the subject itself. I’m currently working on a personal project to document the decline of the high street in my town. I’m visiting and revisiting the town centre as part of my daily walk and trying, without bias to capture the changes. When I started the work, I hadn’t begun this course and in terms of reflection I realise that I am both inside and outside. I am passionate about my home town after living here for 20 years and the fact that I have friends who own businesses here makes me an insider. However, I’m not a business owner by profession and so don’t fully appreciate or connect with their struggle, which in turn makes me an outsider. I’m also conscious of the glimmers of optimism that are around the town which I am photographing in equal measure, trying to maintain a balance. All of my photographs to date have been devoid of people, but trying to capture the essence of the business that was there before. I guess I have been subconsciously trying to work more like Rosler. The long term nature of the project means that this may evolve as things change around me. In conclusion, I believe that balance of subject, empathy and perspective of the photographer is the compromise to achieving as objective document within a single photograph or series. I’ll revisit these thoughts are the project progresses.

References

[1] Reeves, E, 2017, “On the Ballad of Sexual Dependency”, MOCA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iDSvD0yhjWQ

[2] O’Regan, K, 2019, “Diane Arbus’ unflinching portraits of outcasts are more impactful now than ever”, Sleek Magazine, https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/diane-arbus-hayward/

[3] Finn, B, 2019, “A new book documenting Nan Goldin’s journey through drag”, HERO magazine, http://hero-magazine.com/article/159524/a-new-book-documenting-nan-goldins-journey-through-drag/