The Brief

Read the section entitled ‘The Real and the Digital’. in Wells, L (ed.) (2015) Photography: a critical introduction (Fifth Edition) London [England]; New York, New York, Routledge. pp 92-95.

Does digital photography change how we see photography as the truth?

Consider both sides of the argument and make some notes in your learning log.

The Arguments

The article puts a number of arguments forwards about the rise of digital media and its impact on what is ‘real’. Broadly speaking, it is argued first that far from being a technical curiosity that seeks to mimic traditional photographic method, the advance of digital techniques will eventually evolve into a medium in its own right; imagery claiming to be real having being created entirely from scratch. This evolution makes it virtually impossible to seek out the truth in an image. The argument that truth is found by the connection of the image to the trace of an event (Barthes) is challenged by this ability to create from nothing. The counter argument is made that perhaps it isn’t necessary for a photograph to be single-handedly based in truth as the evolution of visual media as a whole has transformed how traditional documentary is achieved. Buadrillard and Campany support the lack of a point to representing the reality of an event when the story is much wider than what is happening. The latter going on to say that photography has never been self-governing or reliant on technological factors, more how it is used and to what end. The rise of the ‘citizen journalist’ with their handheld devices places the ‘photographer’ firmly in the action, making it appear a more honest and real report. This has replaced the level of separation present in traditional documentary photography between subject, editor and the public but achieves a similar goal. Citizen photographers publish to the world via social media platforms and to some extent, control the audience for their images. News outlets pick up this media via the same technology and so, the evolution of this style of documentary is argued to be spelling the end of traditional documentary as we know it.

Analysis

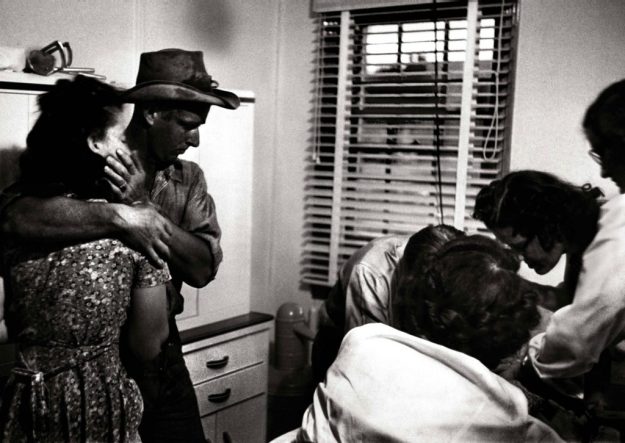

The first and possibly most obvious argument about the rise of digital photography techniques is one that I can directly relate to, being relatively inexperienced at using editing and manipulation software. What I have learned has been entirely self-taught, using online video tutorials on YouTube. Like many, I started with wanting to know something specific and have experimented in the margins around that particular topic. What has been clear to me over the years is the rate of change. Adobe Photoshop used to be a single program, updated every year or two to bring enhanced feature sets to its devoted users. In recent years however, the software has moved to a subscription platform where now it appears that updates and functions are added much more frequently. Whenever I use the software now, I’m acutely aware of the distance between its limitations and my own capabilities. Far from mimicking what could be done in the darkroom with paper, chemicals, toning, tinting, Photoshop allows for the creation of fantastical images with relative ease. In Exercise **, I created a composite image of my face blended with a phrenology bust and the result was haunting in appearance but had that element of truth that Barthes referred to in his assertion about the trace of an event. In the photograph, my eyes and hair are very real, but the glassy surface of my new skin with its virtual tattoos of the areas of the head are clearly not. The alignment of both images is sufficiently accurate to leave the viewer wondering what I am. Is this the face of a doll or some experiment in robotics that one might find being reported in some science and technology publication? What digital media has created then is an image that our first instinct is to believe and second is to question. As Baudrillard stated though, the event itself isn’t the story but the factors that surround it and the sensationalism or enthusiasm at how it is being reported that tells the truth of it. In the case of my photograph, its not that clear a connection to draw. However, the Victorian ghost photography that was created with the similar but more primitive technique of double exposure, had a different cultural meaning. The Victorians were a superstitious and spiritual generation that wanted desperately to believe their loved ones went onto another place after death. They treated their dead in a way intended to be as normal as possible, including photographing their corpse in a living scene (below) and many of the traditions we have today with regard wakes and funerals trace back to their time.

Two Victorian death photographs. On the left, the dead woman is posed with her parents and appears sharp during the long exposure compared to the living. On the right, a more conventional documentary tribute [1]

Imagine the shock and joy of discovering that photography could capture the spirits of the departed. As photography was a serious technical endeavour, its use (Campany) was never questioned by the unsuspecting public. If they had done, they would have uncovered the fraud being committed by the photographers who deliberately sold them images that were manufactured in the darkroom. In this case, the social clamour for photography to be truthful outweighs the event being captured, with manipulation being a method to achieve an intended goal.

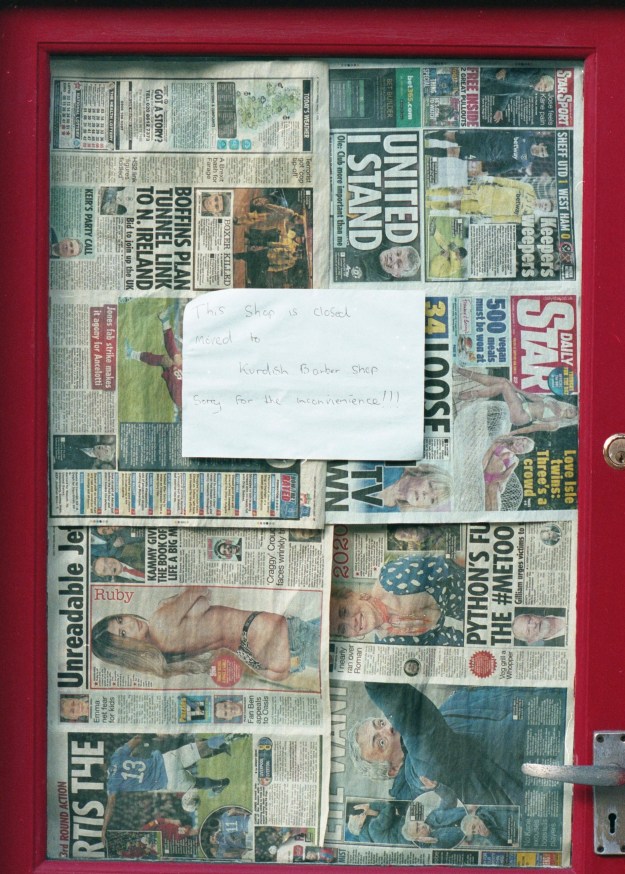

The other argument being made is that the evolution of digital media alongside photography has lent truth to stories that we wouldn’t ordinarily believe or want to focus on. With citizen photography placing the ability to document an event in the hands of everyone with a mobile phone, the news is captured and made accessible every minute of every day. This bombardment of news via social media and through the online presences of traditional news outlets, makes it difficult to see what is real and what is not. Now we have Barthes’ traces of the event, combined with the availability of high resolution video in the hands of the masses and also the socio-political temperature stoked by social media and 24hr news. The phrase ‘truth and consequences’ perhaps more than ever, has a relevance in modern documentary. An example of this happened in my region in 2016. A photograph was shared on social media of a man sitting in a pub garden, wearing a very offensive t-shirt that mocked the deaths of the 96 victims of the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989. The edited image is shown below:

This image of the man first appeared on social media. The text was pixellated by the news outlet reporting that he’d been charged with a public order offence [2]

The image was shared as a statement of the horrific poor taste of the t-shirt that the wearer claimed was ‘banter’ at the time of the incident. However, the strength of feeling in the UK about the Hillsborough tragedy meant that it was circulated widely and quickly at the same time that the police were investigating the man for a public order offence. The impact of this viral explosion was that the man was quickly identified by people who were present at the pub and soon after that, he was tracked down via social media and made the target of hate campaign. When the case came to court, the man was fined for the offence but he stated in court that the incident had cost him his job, home, relationship and friends. He spoke of his remorse for what he had seen as fairly harmless and accepted that the punishments fitted the ‘crime’. In the context of the crime committed, it is difficult to see its severity but in the context of society and the pain caused by Hillsborough that is still felt 30 years later, the incident was hugely offensive to a great many people. What interested me about the coverage when I was looking for the photograph for this essay was that the mainstream media outlets all elected to pixellate the text on the t-shirt so as to not cause further offence. However, some online news sources were not so accommodating. For me, this plays to the traditional model of the editorial defining how the story is told, despite being of the modern era.

The final point made in the source material was that traditional magazine photojournalism has been in decline for many years because of the way that events are recorded using mixed media. This makes sense as many magazines have had to move their focus online as this is how many people consume their content. The need for high-quality, carefully photographed subjects is still there when it comes to lifestyle, travel and the review of art. However, there is a move towards the authentic experience particularly in travel, which is becoming increasingly satisfied by travelogs and Instagram rather than the traditional glossy publication. I am reminded of a training course that I taught at work where we explored entrepreneurship in the 21st Century. I would tell the story of having to flick through glossy travel brochures where the hotels were shot sympathetically to emphasise their scale or in some cases hide building works. The imagery was always oversaturated, shot in ideal weather and generally made to look like somewhere we would want to visit. Now, of course with the invention of the travel review sites like Trip Advisor in the early part of the century, we want to know what people really think. The power to make or break a holiday offering now sits with the people as part of the media revolution we’ve all had to adapt to.

Conclusion and Reflection on Part 1

In conclusion, the argument that photography can be used to create a false truth is something that I accept both as an engineer and as someone trying to develop their own creativity. However, I strongly believe that people make their own mind up what is real and what isn’t. The photograph needs to have a trace element to something believable as Barthes asserted, but that trace can be miniscule. The contextual elements in a photograph on their own might lead the viewer to reach the ‘truth’ of the image, but it is more likely that their personal experiences and what is happening around them influence the conclusion that they reach. The rise of digital and social media mean that people associate truth with the ‘herd’ mentality. To that end, digital media has changed the way we see the truth in photography. With the Gulf War example that Baudrillard controversially stated ‘didn’t happen’, our perception of the politics that took a previously supported dictator in Saddam Hussein into an invasion of a neighbouring country, shaped the way we saw the news of the conflict untold. Instead of describing something that backed up our assumed knowledge, we should think of what truth there is in Baudrillard’s comment about the conflict rather than dismissing it.

At the start of this unit, I assumed documentary photography to be a straight capturing of the event at hand. In a similar way that at first glance, the decisive moment is seen as an accurate slice of time, I believed that documentary was the no-frills view of what is happening. However, we know that the decisive moment says little about the pattern of life, the events leading up to and immediately following the snapshot, so why is it such a departure to question the truthfulness of documentary? Documentary for me is a perspective on an event that we are encouraged to believe, e.g. the FSA images of American migrants. It blends the reportage of showing only what is needed and seeks to tell the story in either a single frame or series (Cartier Bresson, Lixenburg). The concepts of being part of the story and being an observer were new to me. When comparing the works of Arbus and Goldin, I could clearly see how their differing viewpoints of trans-sexual people provoked different emotions in me. While Arbus’ observations appeared to focus on the strangeness and unrecognisable, Goldin’s work is warm and affectionate towards the people who were her dearest friends. Lixenburg achieved the same sense of belonging by becoming part of the community that she was photographing, while still not entirely relating to their plight.

I also learned that when the frame or series contains space for interpretation, we start to move into the realms of documentary art (Seawright, Pickering). Too little context and the viewer creates their own fantastical narrative. Too much and the viewer is signposted to the point of the image. Seawright’s Sectarian Murders collection struck a chord with me as each image takes on greater meaning with the external text as context. Overall, I would say that my understanding of documentary has shifted significantly in Part One with a focus on challenging my interpretation of the image, while not getting hung up on the truth.

References

[1] Bell, B, 2016, “Taken from life: The unsettling art of death photography, BBC News Article, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-36389581

[2] Stewart, G, 2016. “Man charged over offensive Hillsborough T-shirt”, The Liverpool Echo, https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/man-charged-over-offensive-hillsborough-11403422