How does a photograph contain information?

In starting this project, my first concern was what appeared to be a generalisation that photographs are all somehow informative. The quotation by Flusser further suggests a quest to inform through ‘improbable’ images that offer something new. My instinctive reaction to the quotation when I first read it was “Do I do that?” When we consider the meaning of the words ‘information’ and ‘improbable’, the quotation makes more sense.

noun:information.facts provided or learned about something or someone.“a vital piece of information”adjective: improbable.not likely to be true or to happen.“this account of events was seen by the jury as most improbable”

It would appear then that Flusser was referring to the creative process of ‘informing’ the viewer about the subject, but in a way that isn’t quite real or believable. We have learned already how the context of an image can change the perceived meaning, but when we consider the internal context, that is what is present in the image, we have the ability to shape the meaning further through information or even disinformation. In the course notes [1], the statement that a well exposed photograph contains more information than one that is under or over exposed is certainly true when considering an image as a technical achievement. The way that light is represented on the ‘sensor’, whether film or electronic is the something that we strive to do with camera skill, but this achievement has little to do with the information that the photographer is trying to impart in the photograph. The amount of information about the subject is completely under the control of the photographer, but whether or not that is what the viewer chooses to ‘consume’ is something that is again a potential contradiction. In their blog article on information [2], the Oxford English Dictionary describe themselves as a vast source of information made more readily available by the internet age. With all of this information to hand, their top searches for word meanings always include the word ‘fuck’; perhaps then, people’s interest in titivating swearwords means that they are more likely to consume that than what else is on offer. The article also quotes President Obama as saying ‘information is a distraction’, which points to the way that the message cam be lost in amongst other information. When we consider the technical use of depth of focus in photography, we can use a large aperture coupled with a long focal length to pick out the subject from the background. It follows then that photographers can use their technical skill to control the risk of information distraction or overload. I have found in my photography that landscapes are the biggest challenge to me, because I am striving to describe the beauty of something that I am seeing within the vista in front of me. However, the usual convention for landscape photography is to include as much detail about every element as possible. An example of this can be seen below.

Santa Barbara Beach 2019 by R Fletcher

This photograph was shot during my recent holiday in California. It’s pretty conventional in terms of composition with leading lines, rule of thirds etc. It was also shot at a fairly small aperture at f/11 to preserve detail throughout the depth of the image. However, what I wanted to convey was the hazy California light and how the mountainous regions are almost always blanketed in a fine mist (or just plain fog). The challenge is emphasising that without losing the rest of the detail of what is a typical paradise beach on that coastline. There is nothing about the image that is unreal or improbable, it is just factual.

Less is More

When we look at Kawauchi’s work in her book Illuminance, we are presented with what at first glance looks like minimal information about the subject. Overexposure and colour saturation create the improbability, but when we look closer, the information that is needed to create that sense is there but just concentrated. The shot below from her book is my favourite image from the book.

Untitled, by Rinko Kawauchi, from her book Illuminance [3]

In Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography, he discusses the difference between the way we read text and how we look at photographs, the suggestion being that the former is linear and the latter, more of an ‘orbit’. This theory reminded me of when, as a teenager, I read the original version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Published in 1818, it was beautiful crafted, certainly using language and sentence structure that I wasn’t familiar with at the time. Shelley also used embedded narrative to structure the story, where a number of characters and the writer herself assume the role of narrator. The book unfolds with these viewpoints layered and interconnected, which requires ‘care’ when reading. What I mean by ‘care’ is that important information can easily be missed if the reader is not concentrating. My experience was that I would have to re-read some passages and even sentences to ensure that I was following the plot this, perhaps the most original horror story ever written. Surely this is at odds with Flusser’s assertion that we don’t re-read? In fact, it supports his notion that we consume the words linearly enough to understand what they are saying, where his comment about re-visiting photographic information is very different. In this case, the viewer returns to the information either to gain further understanding or simply because it is what provokes the biggest reaction. It could be that the information is not understood or that it is somehow unbelievable or improbable; the continued re-visiting being some way of trying to make sense of it.

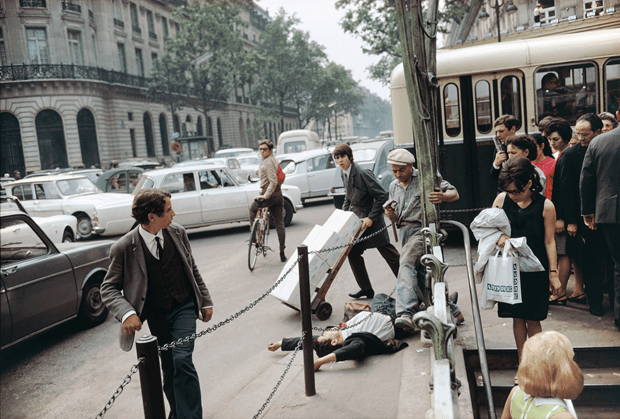

As I’ve mentioned previously, my favourite street photograph is Joel Meyerowitz’s Paris France, 1967 because it has always appealed to me.

Paris France, 1967 by Joel Meyerowitz (from Taking My Time, Phaidon)

Looking at the photograph again, the context that I interpret comes from the information in the image. The man lying on the ground with the hammer-carrying man standing over him and the public looking on. The scene is clearly of the 1960s time period which presents as familiar but somehow different to someone like me who is in their mid-forties. When I view this photograph, I keep coming back to the expression on the face of ‘hammer man’. Is it shock at an unfortunate fall? Or concern? Or is it the anger of an aggressor? Meyerowitz considers this to be his greatest photograph and has been reluctant to give any information that supports any contexts. For me, this certainly preserves the mystery of the photograph and means that I never tire of looking at it every morning (I have a print on my bedroom wall).

We can use this photograph to support the idea that John Berger discussed [4]. In his book, Berger describes the painting as presenting everything in a single moment to the viewer and it being their attention to each element that allows them to draw some form of conclusion. He contrasts the single frame to a moving picture film where the instant now has time added to it. The next image on the film strip will have different information that the viewer needs to consume quickly in and in sequence, in the same way as the written word. For a single image, then this return to the photographs for new information has an almost a cumulative effect on our interpretation of the subject. When it comes to the improbable, this can be an instant reaction as it was when I first saw Paris France, 1967. Surely the man could not attack someone in broad daylight. What happened in the instant after the event? Did the man help the other up because it was a mere tumble in the street or was he arrested? What part did Meyerowitz himself play in the scene that followed? If it had been a movie, we would simply have to wait for the answer. Like Berger’s comment that ‘paintings are often reproduced with words around them’, the photographer can choose to do the same or provide nothing to support or contradict the perceived context. What they have is a toolkit to make the believable unbelievable with a single 2-dimensional view of the world.

References

[1] University of the Creative Arts, Expressing Your Vision Course Notes page 108.