A Different Experience

I’ve made no secret among friends and colleagues that my long term plan is to move away from engineering and to teach photography. I made this decision shortly before starting this course, after realising that the most enjoyable thing about my job was mentoring and coaching people at the start of their careers. Combining what I’ve learned about photography over the past 10 years with trying to inspire people with my passion for the medium, is what I plan to do for the remainder of my working life.

This has been well received by all those I’ve discussed it with, so it was a wonderful moment when a member of my work team approached me with a proposition last month. The primary school that her son attends has an ‘Aspirational Week’ every year, where a number of guests are invited to talk to the children about their careers and interests in an effort to inspire them. I don’t recall anything like this when I was at school; careers were encouraged by pushing the children to quickly make their minds up toward the end of their secondary school education. I thought this was a wonderful idea and was very excited when she asked me if I would be interested in talking to the children about photography. A conversation with the teacher resulted in a plan for me to talk to around 60 children between the ages of 8 and 10 in two presentation slots. I planned a brief talk about how I got into photography and the showing of a couple of the more interesting cameras from my collection. My props included some prints of photographs made by each one, a strip of negatives with images on them and a 4×5 colour slide for them to look through. The star of the show was my Graflex Crown Graphic, which was set with the lens open so that they could see each other upside-down in the ground glass. After my talk, they would get to practice some basic composition techniques (rule of thirds, uncluttered backgrounds, framing etc) using the school’s iPads as cameras. Each session went as planned and as they enthusiastically started shooting pictures, I started to think about creativity and how it evolves.

One of the children had asked me what I took pictures of and my answer was “whatever interests me or whatever I like”. I realised that this is probably the starting point for all photographers. I certainly remember pointing my first camera at anything and everything, without caring much about what was in the frame or whether it was in focus. When we completed the iPad exercise, I was staggered at the quality of their images. Being a primary school, the building we were in was brightly coloured with examples of the childrens’ work on the walls. Almost every child in the room used their environment to make their pictures more interesting. They were utilising my very brief lesson on composition, but were seeing patterns and colours as well as related subjects when framing their shots. To the casual observer, they were randomly running around, but their ability to see things and shoot was quite remarkable.

The stand-out image was shot by a lad who was fascinated by the Graflex earlier. His shot, which I don’t have for obvious safeguarding reasons, was very similar to one of my pictures from Assignment 5 (see below) where I shot a self portrait through the ground glass.

Eight, from Assignment 5 showing me inverted in the ground glass of my Graflex

What surprised me about the picture was how quickly he had seen the potential for combining both the inverted subject in the ground glass and as seen past the camera in the far field. He placed the Graflex in the far left of the frame in order to fit it all in. The resulting image was his friend inverted (in focus) and him as ‘normal’ with a small amount of bokeh in the background. The shot was exposed properly, which was to be expected owing to the technology in the iPad camera. However, what stood out for me was the fact that when I shot the above photograph, it came from an idea that took several hours to mature and perfect as part of my theme for Assignment 5 and here was a young boy shooting something very similar and of excellent quality in a matter of minutes. How could this be? I asked myself “what happens to our creativity as we get older?”

Was it a one off?

In an effort to understand what happens to our creativity, I first wanted to make sure that it wasn’t an isolated event; this boy and this class weren’t just the result of a great school (it has an excellent reputation in the area). I thought back to the last time I spent time with children and cameras, which was back in 2015. I was on a photography holiday in Marrakech with a group of other keen amateurs and our tutor. We were staying at a retreat on the outskirts of the city that was owned by two former UN workers from the United States. Their retreat was specifically for holidaymakers, but the owners also ran a community project called Project Soar. The project was aimed at educating and inspiring the young girls of the local area; part of the progressive movement in the rural communities of Morocco. During our trip their ‘activity’ was photography, which involved us ‘students’ handing over our expensive DSLRs for the girls to shoot with (on Auto). The resulting images would then be printed for the girls to keep. As the session progressed, I began to notice that the children were moving quickly around the retreat, shooting their friends against a variety of backgrounds and with a selection of teenage poses that they had picked up from the culture of their US teachers. They were not dwelling on a place or composition, but shooting and moving on to the next location. As with the children at the school, they were taking many photographs and because of the automatic capabilities of the camera, were getting successful exposures most of the time. I contrasted this with my own experience as a child where the sophisticated electronics of modern DSLRs did not exist; my ‘hit rate’ was far lower and much more disappointing when the film had been developed. The photographs that the girls of Marrakech had taken were similar in their quality to those at the school but there was also the same attention to the relationships between elements within the frame, related colours and textures and in some cases even the way the light fell on the subject. Their unrestrained enthusiasm for creating an image outweighed any technical or artistic knowledge and, like the children at the school, it really didn’t matter.

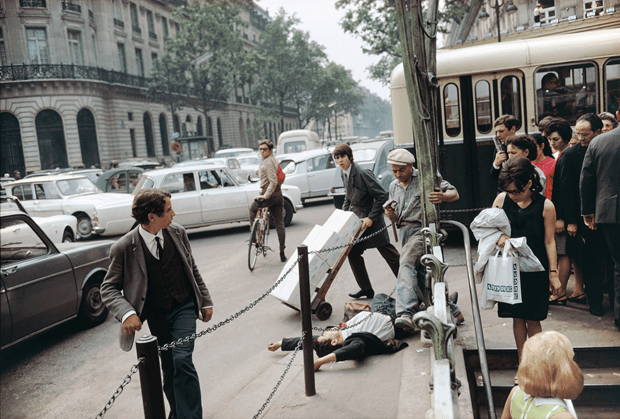

One of the shots from Marrakech taken by the one of the students

With these two similar experiences with groups of children of similar age groups and completely different backgrounds, I concluded that what I had seen was no lucky accident. I started to think about what might be behind my observations.

A Theory

When we are very young, we have no rules. Our parents begin our upbringing by prescribing standards, i.e. what is acceptable or unacceptable, what is right or wrong. For example, my parents instilled in me that I was responsible for my younger brother’s behaviour when we were out playing. My brother was always a more lively child than me and wanted to explore and take risks that were not my first instinct. When we inevitably got into trouble because of that, it was me that was ‘held responsible’. Years later, I understood why my parents wanted that to get this message across, but as we were only two years apart in age, it was never going to be realistic proposition. It follows then that we begin to apply those rules to daily situations and test their effectiveness. This learned behaviour tunes and increases our sense of ‘the rules’ and influences our behaviour.

The same can be said of how we try out things that we might be interested in. We have not real clue how things should be done, but we have a go and see what the result is. In my case, I loved the understanding of how my first camera (below) worked and the act of pointing at a subject but I had no idea how the image would turn out. I certainly wasn’t seeing what was in the frame and the happy accidents of good composition were rare. However, the hiatus between my early attempts and photography and my first DSLR included many opportunities to learn about my process of learning. By the time I had taken a serious interest in photography, I knew that I needed to understand the technique and to look at what makes ‘a good picture’. That became the basis for my taking photographs, rather than what I was trying to capture or say about the subject. For me, it is that which separates adults from children and sets boundaries to both our learning and our ‘creativity’.

The Voigtländer Vitoret 110 – This was the first model camera I used as a child

In the case of the children, they saw what they liked or had an interested in and pointed the camera at it, without fearing disappointment in the result or believing that they had made a mistake; there was no mechanism that would hinder them. With the digital cameras, they could quickly review and discard if necessary. The key difference being that they had no investment in that particular image so if it didn’t work, they moved on. At the end of both sessions, the school children were asked to show their two best pictures and every child quickly decided upon their favourites. This could be because they weren’t concentrating on why they had taken the picture in the first place, so were re-discovering it or that they were filtering or mentally censoring the images as they were shooting them. Either way, they were not overthinking the process, the result or what the image meant to them because they had not had the experience of building rules or barriers to learning.

On a recent training course that I attended, I was introduced to the concept of ‘limiting beliefs’ [1]; the idea that we create barriers to doing certain things because we believe we will fail at them. Experience and education both have the ability to create these barriers because the fear of failure is common in almost everyone, resulting in us trying everything possible to avoid it. With no real experience or teaching in photography beyond exposure to the technology, the children didn’t fear failure but instead just wanted to enjoy the activity. Further research for this essay led me to a TED presentation by Dr George Land [2], who discussed a study carried out by NASA on creativity. Of a sample of 1600 children aged 4 to 5 years old, 98% of them met the study’s criteria for ‘genius’. When they tested the same group of children 5 years later, the number fell to 30% and on to 12% when they reached the age of 15 years old. By the time the sample were 30, the number was a mere 2%. Land’s explanation wasn’t that they had somehow lost intellect, but that their thinking had moved from Divergent, that is idea-generating, inventive, to Convergent which is more problem-solving. Education was what taught the children to combine both ways of thinking and their experience of growing up meant that they built internal rules, criticism and censorship of the creative part of their minds. It would appear then, that my observations during the school visit are validated to some extent and that the children were unlikely to be mentally censoring their images during the exercise.

Conclusion

My visit to the school was a learning experience for the children and for me. Most of them had never seen a film camera before (although one told me that their dad had a shelf collection of cameras he never used). They had never held a positive slide or strip of negatives up to the light to see an image. I had explained to them that when I first experienced these things, I believed photography to be magic, something that they all were quick to agree with. The children had also never seen how a simple camera obscura could produce a picture, with most of them not believing it was a camera to begin with. However, what I learned was important also. Children are completely free to think divergently and do not fear making mistakes or not achieving what they set out to do. By contrast, I realise that my photography has become very controlled by rules and generally accepted wisdom, which has often been at the detriment of the original idea or inspiration. Surely this much change somehow in order for me to improve artistically.

“To stimulate creativity, one must develop the childlike inclination for play and the childlike desire for recognition” – Albert Einstein

What Einstein was saying is similar to Land’s conclusion in his TED talk [2], that we can access the area of our brains that works creatively, but in order to do so we need to become more like children in our outlook. I’ve made many references to my engineering background and the challenges of letting that go to become an artist. For me, I feel that I’ve learned a great deal about photography both before and during this course, but I need to find a way of looking at my art as a young boy before I apply that learning. . If ever there was a perfectly timed trigger for this realisation, my school visit must have been it.

References

[1] Burnford, J, 2019, “Limiting Beliefs:What are they and how can we overcome them?”, https://www.forbes.com/sites/joyburnford/2019/01/30/limiting-beliefs-what-are-they-and-how-can-you-overcome-them/#3fe8a9386303

[2] Skillicorn, N, 2016, “Evidence that children become less creative over time (and how to fix it)”, https://www.ideatovalue.com/crea/nickskillicorn/2016/08/evidence-children-become-less-creative-time-fix/