The Brief

Take a series of 10 photographs of any subject of your choosing. Each photograph must be a unique view of the same subject; in other words, it must contain some ‘new information’ rather than repeat the information of the previous image. Pay attention to the order of the series: if you are submitting prints, number them on the back. There should be a clear sense of development through the sequence.

Initial Thoughts

Simple (adjective): Easily understood or done; presenting no difficulty – from Oxford English Dictionary

Throughout this course, I have resisted the temptation to read ahead as I wanted to progress my learning in a linear fashion. I guess my engineering background is probably the reason why I tend to look at things this way, however, I wrote this initial preparation paragraph while working through Part 4; following a recent course video conference with Robert Bloomfield. In that meeting, Assignment 5 was discussed at some length, in particular the fact that the open brief causes many students struggle with where to start. To get a head start, the first section of this post outlines my initial thoughts on my subject and how it links to the brief.

Photography is simple? I must admit to never having seen it that way. What I have observed is my continuing quest to make my photographs interesting, or at the very least not boring. As a technical person, I’ve also observed the increasing complexity of the ‘process’ of photography, that is the way that camera evolution has almost made it easy to take the same photograph as the previous, or the next person. When I started to ‘rebel’ against my DSLR a couple of years ago [1], I slowed things down and started shooting with all manual, film cameras to improve my technique. This would allow me to focus on the look and feel of how I wanted the image to look, but ironically the technical rigour of film took my attention away from really looking at the scene. During this course, my attention has shifted back towards the subject and what I’m trying to say about it. The discipline of creating a series of photographs has been a worthwhile change to my approach.

When starting to think about the assignment, I was drawn back to the research I did in Part 4 on how painters, in particular portrait painters, manipulated light. They are able to conjure light where it perhaps wasn’t previously present and interpret what is there to create the shapes on a face or figure. Rembrandt was the master of this work and for this assignment, I wanted to play with some of the simple lighting arrangements that he was famous for. For the subject, recalled Assignment 2 and how people reveal their emotions through the eye area of the face. I’m always fascinated by what makes us different and how we value that which we hold dear. My subject could therefore be the evolving way that people ‘cherish’ as they get older, which will provide the connection between what the brief describes as the information in the series.

I started to consider the concept of Window or Mirror, which was the topic addressed in the video call and a way of looking at how photography has evolved in its use. The contrasting ideas of a photograph that reveals the subject in its truest form (the window) vs. the photographer’s perspective or views on it (the mirror), is a thesis well understood within the art. Szarkowski’s book on the thesis [2] describes three significant photography releases during the 1950s; the first publishing of Aperture Magazine, the ‘Family of Man exhibition at MoMA and the publication of Robert Frank’s The Americans. Each of these events had an impact on photography as a modern medium, but for a variety of audiences and used photography in a different way from each other. Aperture Magazine, although well known today reached a fairly limited audience at the time of its released. This was considered to be because of the steady decline of the traditional photo magazine owing to their subject matter being more accessible to the public with advances in worldwide travel. As with the publications it competed against, Aperture’s mission was to reproduce photographic works that revealed the subject in the best possible way (Szarkowski refers to the Adams and Weston ‘quest for the perfect negative’) and wasn’t really interested in anything more than documenting what was in front of the lens. While influential to a whole raft of young photographers and of passing interest in magazine terms to a wider audience, Aperture’s initial impact was fairly limited. By contrast, The Family of Man was a highly successful exhibition that revolved around the premise that all people were fundamentally the same although demonstrably not the case. The photography for the exhibition was essentially curated to look the same from a technical perspective, while the subject matter varied considerably within the theme. The people that saw the exhibition could relate to the familiarity and be challenged by the contrast. Finally, The Americans looked at 1950s American life from the viewpoint of Frank. The book highlights the social, political and racial tensions and contrasts the lives of members of the class systems in the US during a period of great change. With these three events, we have windows and mirrors and a combination of both; Aperture’s window on the world with its many different photographers revealing the subjects as best they can, Frank and his “searing personal view of this country the Eisenhower years”[2] mirroring his view of America into the public consciousness, and in the exhibition both cases. The subject is revealed in a documentary style, but with the approach taken by MoMA to have consistency in the images themselves. Here, the museum is forcing the perspective without necessarily changing the way we look at man, beyond the stark contrast of our similarities with differences. For me, the categorisation of how photographers work with their art isn’t the important concept, but how simplicity of connection can make or break what the image means to the viewer. I attribute this to the way I’ve historically looked at photographs, that is with much more bias toward the ‘window’. When I first looked at The Americans, I struggled to make powerful connections between the images as to me, the seemed illogically ordered and often obscure in composition. However, in progressing through the course, I’ve come to appreciate the visceral nature of Frank’s photographs as both a factual snapshot of 50s America, but also a bold statement of where the American dream had issues; something still very evident 60 years later.

Taking a Step Back

Following the completion of Assignment 4, I had a call with my tutor for feedback during which I asked how he thought I was doing so far. My concern has been that I’m most comfortable with the technical aspects of photography than the artistic and I was keen to know from my previous work, what my tutor thought. His feedback was that it was clear that I knew my way around a camera and the technical skills of shooting both digital and film. However, these strong connections with the technical are evident in how I approach the work, often with the elements that link a series together being something to do with how the photograph was taken rather than intention. The feedback was that I needed to look more closely at connecting the images with something more subtle, expanding more on the what I am trying to say about the subject and its context, than the technical achievement of shooting it.

At this point, I had a loose idea of shooting a subject with a single camera for my 10 images, but the idea revolved around the simplicity of the camera itself. My medium-format pinhole camera is one of my favourites because of the unique look of the photographs it makes, but also the simplicity of its use. For the assignment I planned to shoot portraits of people with the theme of something they cherish or treasure with this camera and I went to the lengths of working out how long each exposure would be depending on the film, reciprocity failure etc etc. This recent feedback, though had made me realise that once again, my ideas were technical; the camera is very simple to use, but the skill required to use it is much higher and I was drawn to how clever it would be. I think this can be described as a ‘lightbulb’ moment which required me to reconsider this assignment; take a step back.

Ideas…Ideas…Ideas

With the objective now to connect to the subject in a way other than technical, I started to review the constant theme that has been running through my work on this course to date; revelation. As the brief calls for new information in each photograph in the series, my approach to composition or what is in the frame, would be similar to previous work. With regard to Window or Mirror, though how much would the subject reveal itself naturally and how much of my perspective would encourage the detail to be revealed?

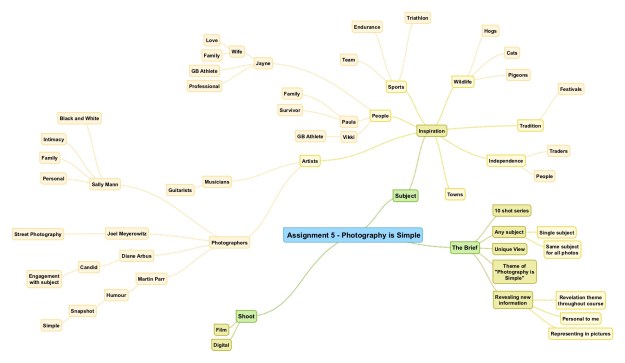

I started with thinking about the things that inspire me and created a mind-map. Mind-mapping has been a useful tool that I have used in my professional career, so my thinking was that I could use this to help encourage inspiration for this assignment, My mind-map is shown below:

While I’ve been interested in architecture and landscape for many years, my studies have moved more towards shooting what I’ve referred to as ‘pattern of life’, most of which involves people being in the frame. Assignment 3 on The Decisive Moment was the most challenging so far because of how I find shooting people an uncomfortable experience. Not wanting to duplicate the classic street photography style, I came back to my original thoughts about portraiture, which left me unable to decide who my subject should be. Lots of people inspire me, from my Dad who was the person who introduced me to photography in the first place (and has encouraged me ever since), to my wife Jayne, who’s athletic achievements are a constant inspiration. My friends, colleagues and family all impact on me in more that one way, so perhaps one of them could be my subject. A few years ago, I had the idea of following a friend around during a typical day in their life, which was inspired by the diversity of my friends’ professions and interests. The challenge would be avoiding simple documentary shots with something that obviously points towards the interesting element, for example a racing driver sitting in a racing car. I would need to combine context with perspective to reveal the detail without leading the viewer to the answer; in the same example a close-up of a helmet visor or item of race clothing could reveal the information on its own.

My Idea

The mind-map itself wasn’t all that helpful in selecting a single subject for this assignment, but combined with an important meeting at work, I eventually settled on what I wanted for the series. As I’ve mentioned previously, I work in engineering and am part of the leadership team for our business. Following a recent number of changes to our organisation, we held a 2 day leadership meeting away from the office to work on our future strategy. As part of our preparation for the event, we were asked to put together a single presentation slide called Who Am I? The slide was to contain photographs only, as opposed to a written narrative, that we would talk through as an ice-breaker at the beginning of the meeting. I have done many exercises like this one before, but the concept of describing myself with pictures alone was a challenge. I started with my parents and family and moved through my work, marriage and interests. The challenge here was to find a single image that told as much as possible about me as space on the slide was limited. The finished version of the slide can be seen below.

Who am I? slide presented at a work meeting

In a sense, this was a revelation of the important things in my life and I was happy with the result. The main issue for me was that despite careful selection, I still managed to miss out some of the things I hold dear; my love of motorcycling, the arts and charity interests. This realisation brought Szarkowski’s window and mirror thesis back into my thinking. Photography that exhibited the former tended to be representative and documentary in nature and during the 1950s it became clear that photography was not able to describe the scale or impact of events. Szarkowski refers to Don McCullin’s photographs of the Vietnam war as being powerful and impactful, but that they didn’t directly affect the way that people saw the conflict on a larger scale. It would seem that the window being described is actually fairly small. As Meyerowitz described the viewfinder as the limited view we have by comparison with the field of view of the human eye, Szarkowski concluded that the singular window was not enough. When I was compiling this slide, I paid careful attention to the sequence with regard to logical flow; my parents wedding in the top left corner and my cameras and wildlife interests in the bottom right. In this sense, the slide is a mirror of how I want myself described. Fairly quickly, I settled on the idea form this assignment. My series of shots would be self-portraits that describe who I am. The key differences in my concept would be that in most cases, I would be directing another person to shoot my picture, rather than the now-all-familiar selfie which has become part of our daily lives. The series would be intended to both mirror my own views of who I am as well as show enough of my personality to create a narrative in the viewer. I would bring the simplicity to the series through the composition but not the technical aspects of each photograph.

Influences

When I think of self portraits and their ability to both reveal and mystify, I think of Vivian Maier. Maier was an unknown photographer who was discovered by accident when boxes of her possessions came up for sale in an estate auction in the US. When the new owner started to look through the boxes, he found thousands of images in negatives and undeveloped film rolls. As he started to catalogue and scan the find, the quality of Maier’s work became clear and although the nature of the discovery and its subsequent exploitation divides opinion, she is now a highly regarded artist.

The mystery of Maier for me is that despite the efforts to understand her life and work by the owner of her work, later described in the documentary film Finding Vivian Maier, little is really known about her. This makes the self portraits she took with her trusted Rolleiflex TLR camera all the more alluring. She was noted to be a quiet person by those who knew her, so why would she peer into her own eyes with her camera reflected in the glass of a shop window? I took this as the basis for my series and the simplicity of photography that the brief was asking for.

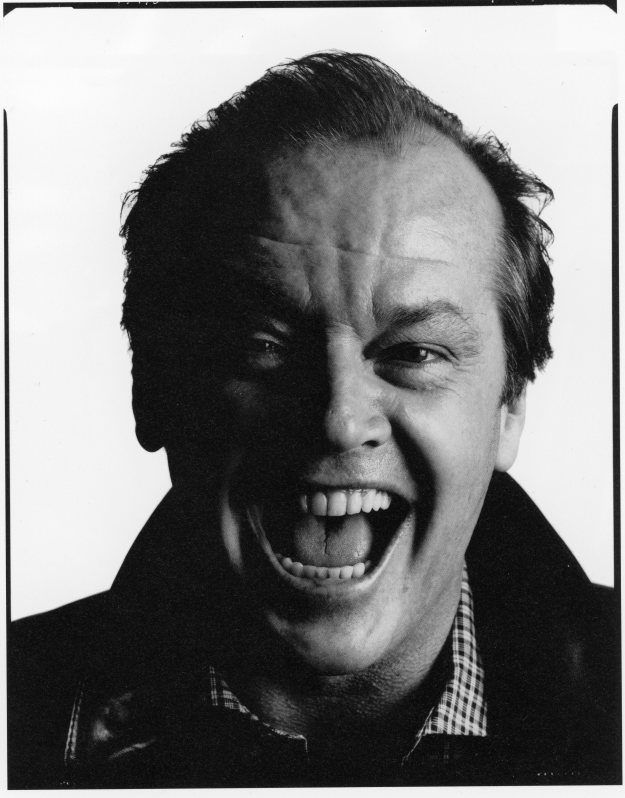

Another portrait influence of mine has been David Bailey. Famous for shooting the famous, Bailey’s portrait work has always appealed to me as his approach is to shoot the subject in an apparently simple, high-key light setup. His most famous work was, of course shot on black and white film, which emphasised the range from highlight to shadow and for me, reveals the complexity behind the simplicity of his images. The engagement between photographer and subject is clear, but we are not sure how much of it is Bailey trying to capture what we know or how much the subject wants to show us. In the case of his portraits then, Bailey is both window and mirror, with the subject playing their part to a greater or lesser extent. One of favourite shots was of Jack Nicholson in 1984 (shown below). When I saw the Stardust exhibition[3], this image in particular made me smile as I instantly related it to another print of Nicholson that I own. Here we have Nicholson in Bailey’s traditional setup, but with a very simple Rembrandt light which I’ve used previously with a single diffused strobe and reflector. However, this photograph is all about Nicholson and his eccentric character. The image works because he is showing us what we know about him, lifting the impact from a simply-lit actor in a contrived fashion pose, to a snapshot of a larger-than-life personality. Like the Family of Man exhibition, here we have the familiar speaking for itself and more importantly, being similar yet very different from the rest of the collection of Bailey’s images. The other image I referred to earlier is a film promotion shot by Herb Ritts of Nicholson in his Joker make-up from the film Batman (1989). The similarity in what the photographs ‘reveal’ about the actor is clear, even though the lighting and composition of the images is different.

Jack Nicholson (1984) by David Bailey from Bailey’s Stardust

Jack Nicholson III (1988) by Herb Ritts []

The Shoot

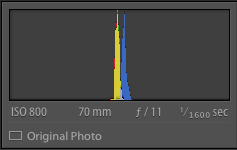

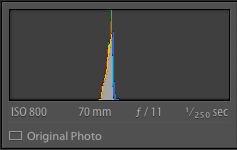

The first aspect I settled on was the basic look of the images. I’m a huge fan of black and white, mainly because of my passion for film and driven the film stocks that are still available. For this assignment, I wanted to combine digital and film if possible and with my favourite film cameras being 6x6cm medium format, decided that the series would be square crop black and white.

Beyond this decision, I wanted to limit my technical thinking and concentrate on the subject. I’ll confess to being someone who does not enjoy having my photograph taken. A friend recently pointed out that the images of me he has seen on social media were either with a serious expression or the extreme opposite ‘clowning around’, with very little in between. This reminded me of my very first conversation with my tutor, where we discussed the importance of constructive feedback, no matter how uncomfortable. I believe myself to have a good sense of humour and the ability to make my friends and loved ones laugh, but am also aware that it’s virtually impossible to switch this on and off. Therefore, my images would reveal something about me in a completely natural expression, whatever that may be.

Equipment

I used two cameras for this shoot; my Nikon D4 DSLR with three lenses (24 to 70mm, 70 to 200mm and 200mm macro) and my Hasselblad 500cm with an 80mm prime lens. The film used was Ilford HP5+, ISO400 stock, which I developed myself at home. I used a variety of light sources, but mainly my Elinchrom studio strobes with soft boxes, grids and snoots. The main addition during this shoot was the discovery of the tethered web-based control for the D4, which I hadn’t known about. This program made setting up and shooting myself much easier for some of the shots.

The Images – Pictures of You?

“I’ve been looking so long at this pictures of you, that I almost believed that they’re real”, Robert Smith, The Cure

Review

One

This shot was inspired by Bailey and his high contrast black portraits and is essentially what many people see in me. I’m a professional with a senior management position, in which I’m expected to fit a certain mould. For the most part, this isn’t a challenge although I don’t wish to be seen as a stuffy guy by the people who work for me. I wanted to express the formal an informal here through the clothes and pose, but maintain a level of focus with my eye contact with the camera.

Two

My Dad and his wife came to dinner recently and he very kindly agreed to sit for this portrait of us both. For most of my life, people have pointed out our family resemblance which actually happened when I talked through the Who Am I? slide at work; my colleagues wondering how I’d travelled back to the 1960s for the wedding photograph! As we’ve grown older, the differences between how we look have joined those similarities; something I wanted to capture in this photograph. The composition was inspired by Mel Smith and Gruff Rhys Jones’ head to head segments in their comedy show in the 1980s. During this shoot, our inability to stop laughing resulted in a number of different versions. I chose this one, because as well as appearance we are also very alike in personality, which has led to tension from time to time; I believe this image reveals these details in what is a simple composition.

Three

Following the death of my mother, I suffered from depression for over a decade which had a damaging affect on me and the people closest to me. Apart from the classical symptoms, one of the noticeable issues was my desire to hide. After many years of support, I started to venture out more both socially but also in terms of what made me happy. Photography for me was one of the interests that came from that time and has been perhaps the most revealing part of who I am ever since. It was my Dad that originally inspired me to pick up a camera, being a professional himself, so I feel this image naturally leads on from Two. This picture is actually a digital ‘multiple exposure’ which was assembled in post-processing.

Four

With that period of my life came also my getting married. My wife has always been a great source of strength and support from recovery to furthering my career and starting this course. I wanted to show my relationship with Jayne as naturally affectionate, but also completely open with the contrast of order and chaos; her straight blonde hair and perfect figure against my dishevelled hair and creased complexion. I emphasised the closeness with the tightness of the crop and softness of light and shadow.

Five

From relationships to interests and what links them. I’m not a natural athlete, but after a long distance open-water charity swim in honour of my late mum, I became hooked. The concept behind this shot was to show the vulnerable guy in Four in a more statuesque pose akin to an athlete. The wetsuit being partly zipped up was to symbolise the transformation from being the slightly overweight forty-something to athlete, inspired by the myriad of superhero movies that surround us today. The biggest challenge with this shot was not overheating as the outfit isn’t designed for the photographic studio.

Six

Leading on from Five is the sense of enjoyment and, more importantly peace that I get from swimming outside. While I swim with others and compete in races, I see swimming as a solitary relaxation where problems can be worked through or let go of. The composition is intended to reveal this, while, my partial obscuration (inspired by the Martin Parr work that I researched when shooting Assignment 3) shows the privacy of being alone in my thoughts.

Seven

Another way that I relax is through my hobbies, in this case the guitar. For this image, I wanted to avoid showing me playing the guitar as I’m very much a beginner. The composition here is intended to show affection for the peace the guitar offers me. My arm and hand are relaxed on the body of the instrument, almost cradling it. I shot this without noticing my hand obscuring the volume control, but revealing the word Tone on the other control knobs. In reviewing this photograph, the absence of volume actually describes how much the guitar relaxes my busy mind.

Eight

Photography is my main passion and more recently, my enjoyment of using film has led to a substantial collection of beautiful old cameras. What I wanted to reveal here is my love of the technical with the aesthetic of the camera as an instrument in a more fun way than simply documenting me with one of them. This shot came about after previous attempt at combining these elements (see Reflection). I wanted something that wasn’t ordinary but that was still a portrait of me, which led to my using my Graflex Crown Graphic. The inverted image of my head and shoulders connects back to the camera obscura, the most simple camera there is, while the rest of by body appears where it should. I saw this as being the way my life has changed, almost turned upside-down by my passion for photography. I used additional lighting to pick out the edges of the Graflex as its shape is unlike most common cameras.

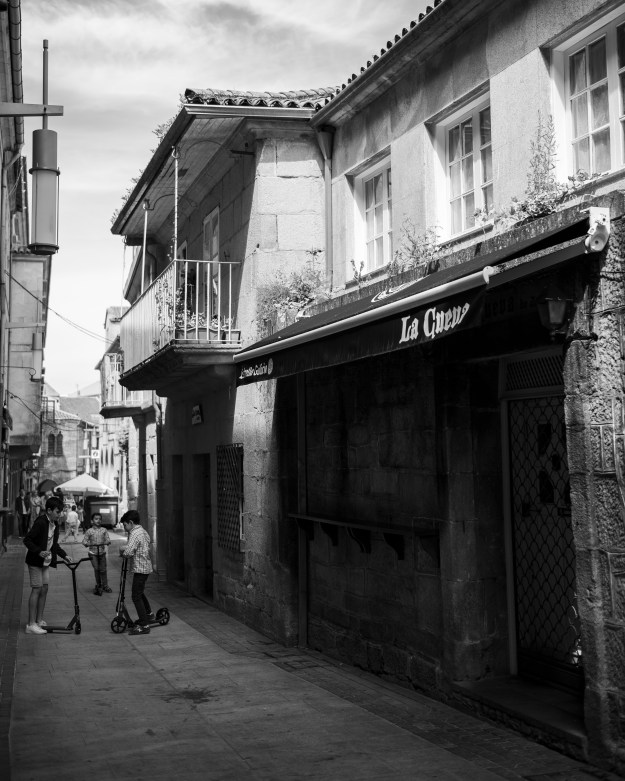

Nine

As well as a passion for photography, I’ve also loved music my whole life, even though I’ve not really played an instrument until my recent venture into the guitar. I’m fortunate to live in a town with its own independent vinyl record shop where I can sometimes be found indulging my interest in both music and the artistic marvels of the vinyl album cover. Inspired by Vivian Maier’s self portraits reflected in shop windows, I wanted to connect these two passions and emphasis my love for film cameras. This image was shot with the Hasselblad in the image, was developed by me at home and led to a more traditional selection process based on a contact print (achieved using Lightroom).

Ten

This final image came about following a visit to Carnival Records in my home town. I’d purchased a rare 12 inch vinyl copy of the single Pictures of You, by The Cure. Having been Cure fan since my teens, this single is one of my favourites and it was made more special by the fact that the vinyl itself is red rather than black. I wanted to use this image to both provide a theme for the series but also to tie it up visually by returning to high-key lighting. As I mentioned previously, I struggle to smile on demand, so in order to create a more relaxed view of me, I decided to blow imaginary dust from the record surface.

Reflection

When I first thought about Who Am I? as a concept, the first things that sprung to mind were the obvious. The slide I had produced for work took significant time to assemble from the many photographs of me within the context of my life. However, when I look at them, they are an almost ‘social media’ view of me, as opposed to something revealing. What I mean be this statement is that by looking at what I choose to share willingly, it is easy to see what is important to me. What it does not achieve is any sense of context. For example, many of my acquaintances see a confident man, while those who know me really well know that the opposite is often the case. Many people know how unwell I was, but very few saw the struggle to return to whatever normality is. In this series of photographs, I have sought to reveal the things that people don’t see through imagery that on the face of it is fairly self explanatory. In terms of the Window vs. Mirror, I would say that I am completely in control of that revelation; that there is no documentary visual associated with the way I’ve shot this assignment.

For the first time since beginning this course, I’ve left my technical head behind and focused entirely on what I’m trying to say. Even so, the technical elements have been highly complicated in creating these pictures, even though the subject and composition is simple enough. That was only the most recent piece of advice from the many helpful critiques by my tutor throughout this course. Following Assignment 1, it was about keeping the theme focused, resisting the temptation to expand the concept to something that could actually fill many themes. With Assignment 2 it was getting that broad feedback and being prepared to change, should that feedback not align with what I’m trying to say. After Assignment 3, I was encouraged to push myself outside of my comfort zone; accepting the difficulty that brings and finally Assigment 4 was about looking for deeper connections that just clever use of technique. I feel with this assignment that I’ve taken these points on board and that the series is the most successful I have been at expressing my vision so far.

What Went Well

As with Assignment 4, I found that I had to stop myself from trying too hard to come up with a theme. The open nature of the brief made this particularly difficult and I found I continually in danger of the huge potential scope problem that I had in Assignment 1. Interestingly, it was an alternative thought about portraiture and turning the camera on myself that started this series. In seeking to reveal myself, I tried lots of things; some working and some not. I’m very happy that each of the photographs leads on from the previous and in some cases refers back to others. Some of the smaller details included in the shots, e.g. the use of contrasting stripes and checks of my shirts in the ‘photography’ pictures were intended to subtly reinforce the subject, in a similar way to Frank’s use of windows and flags in Frank’s The Americans. Above all, I was able to see the images for what they mean rather than how well they were shot. A good example of this is Two, where the reactions of my Dad and I were so different. Dad was a professional portfolio and wedding photographer so was predictably concerned with the composition; me being higher in the frame etc. I agreed that the composition probably wasn’t perfect, but the effect was what I was looking for. I guess, like me, there will also be some element for him of not liking oneself in photographs at play too.

When it came to the strength of what I was trying to say, I concluded that two of my original set were not strong enough and needed to be re-shot. The first (below) was the original concept for Eight.

Rejected candidate for Eight

The rangefinder on my 1936 Zeiss Super Ikonta has a highly reflective mirror that I thought I could shoot my portrait reflected in. The result was fine, but the use of a macro lens to get the portrait left too much of the camera out of the shot, which I felt didn’t do it justice. I also realised that it meant that there were two very similar techniques in Eight and Nine if I included the shot in the series. Replacing Eight with the Graflex brings balance to the series and improves the way the theme flows.

The second image (below) was a candidate for Ten. My concept was to include a ‘happy’ version of me enjoying the record. However, as I indicated previously my discomfort with being in photographs means that I can’t really create a false smile. Every attempt a this shot looked artificial compared to the other photographs in the series. I also realised that the record sleeve wasn’t actually that obvious either, instead potentially looking like a magazine or photograph. I then decided to use the vinyl record itself, knowing that the red colour would present as a lighter tone than black in the final image. By blowing the dust away from the record, I achieved a more natural look.

Rejected candidate for Ten

In terms of the individual photographs, the most powerful for me is the one with Jayne. I had the idea from a picture that I shot of our friends Janet and Bill at the end of Janet’s return to competition following her recovery from cancer[5]. That image was very powerful as although she was the subject of the picture, she wasn’t the only one in the frame. With Four, I sought to show me in the context of the importance of my relationship with my wife. The shot took some patience and careful setup, but both of us reacted the same way to the finished image.

What Could be Better

In this assignment, there weren’t really any significant things I would have done differently. I was challenged to overcome my discomfort with being the subject, which I did through concentrating on what I wanted to say. Arguably I still over-analysed my ideas and tried to force a theme, but quickly remembered my experience with Assignment 4 where I just went out and shot artificial lights to begin with.

In terms of the series, I think the one that doesn’t fit as clearly as the others is Seven, because although it fitted my narrative of the things that give me peace, I couldn’t find another composition that said that without cliché. I’ve seen may close-up photographs of guitars and guitarists using shallow depth of focus to create a surreal effect, but that wasn’t what my connection with the instrument was about. Having settled on the candidate for Seven, I struggled to find another that would work better in the series than the other 8 images. That said, I’m happy with how the image itself turned out. My original idea was to capture my heart-rate monitor reading on my wrist, but the challenges became purely technical and I quickly concluded I was tying too hard to be clever.

Photography is Simple?

This was the theme for the assignment and it became a question for me. As the subject for the assignment, I’m both cooperative and resistive which in any other case would mean that a photographer could let me speak for myself. However, as the photographer as well, I was trying to tell the story of the subject from my own point of view. If my points of view are from the same personality, I am both mirror and window with neither being necessarily the stronger approach. Winnogrand said that he took photographs to see what things looked like when photographed, going on to say that he had a burning desire to see how things looked like when they are photographed by him. These are the classic window and mirror existing at the same time. How can photography be simple in its representation of a subject when this is the case? The answer to the question from my perspective is that the photograph is simply a connection between the viewer and the seemingly familiar. We can limit our vision to the elements in the photograph while simultaneously looking for meaning in the things that are not in the frame. The complexity that makes that connection is the artistry of the photographer. Photography itself is simple, but it has little meaning unless those relationships between photographer, camera and view are in harmony with each other.

Testing the Water

There was one question remaining as I completed this assignment, which was regarding how my personal voice has developed. I was happy that the selection of images revealed what I intended, but as part of the write-up I naturally added external contextual information to each shot. We know from Part 5 that context can be manipulated by factors within and outside of the photograph, so how would the set be received by people without the accompanying narrative? I answered this question by showing the images to my friends, family and colleagues, all of whom know me in different ways. Their reaction was a rewarding experience as each saw the pictures very differently, but understood they connected as a set. The image that provoked the most significant reaction was Four. People saw affection and vulnerability, but also reluctance and distance. The latter pointed to dominance and chauvinism, which couldn’t be further from reality. I concluded that this image in particular created the improbability that we discussed in Project 2 by allowing the viewer to interpret a number different contexts from the composition alone. I’m happy that the assignment meets the brief, but also that my approach expressed my vision as intended.

References

[1] Fletcher, R, October 2018, Learning Log Article “Always Meet your Heroes”, https://richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/2018/10/26/always-meet-your-heroes/

[2] Szarkowski, J, 1978, “Mirrors and windows : American photography since 1960″ – page 16, MoMA. https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2347_300062558.pdf

[3] Bailey, D, 2014, “Bailey’s Stardust”, National Portrait Gallery Exhibition Catalogue

[4] Ritts, H, 1988 “Jack Nicholson III” – http://www.herbritts.com/archive/photo/jack-nicholson-iii-london-1988/

[5] Fletcher R, 2019 “Project 3 – What Matters is to Look”, https://wordpress.com/post/richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog/782

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my wonderfully patient wife for modelling, shooting and offering feedback when I needed to hear it. To my Dad also, who started all this and to Chris Heard at Carnival Records for letting me shoot his shop window.