The Brief

Create a set of between six and ten finished images on the theme of the decisive moment. You may chose to create imagery that supports the tradition of the ‘decisive moment’ or you may to question or invert the concept by presenting a series of ‘indecisive moments’. Your aim isn’t the tell a story, but in order to work naturally as a series there should be a linking theme, whether it is a location, event or particular period of time.

Include a written introduction to your work of between 500 and 1000 words outlining your initial ideas and subsequent development. You’ll need to contextualise your response with photographers that you have looked at and don’t forget to reference the reading that you have done.

Initial Thoughts

The photographer’s eye is perpetually evaluating. A photographer can bring coincidence of line simply by moving his head a fraction of a millimeter. He can modify perspectives by a slight bending of the knees. By placing the camera closer to or farther from the subject, he draws a detail – and it can be subordinated, or it can be tyrannized by it. But he composes a picture in very nearly the same amount of time it takes to click the shutter, at the speed of a reflex action.

Sometimes it happens that you stall, delay, wait for something to happen. Sometimes you have the feeling that here are all the makings of a picture – except for just one thing that seems to be missing. But what one thing? Perhaps someone suddenly walks into your range of view. You follow his progress through the viewfinder. You wait and wait, and then finally you press the button – and you depart with the feeling (though you don’t know why) that you’ve really got something. Later, to substantiate this, you can take a print of this picture, trace it on the geometric figures which come up under analysis, and you’ll observe that, if the shutter was released at the decisive moment, you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been both formless and lifeless. – Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment, p.8.

When beginning this assignment, I was already aware that this is a brief that causes some difficulty among students. Following on from “Collecting” where the objective was to create a strong theme throughout that links the photographs, we are now presented with the additional challenge of supporting or inverting a concept by one of the most influential photographers of the 20th Century. The decisive moment has had its supporters, adopters, doubters and opponents over the past 80 years, so how do we identify with one of these groups while putting our own interpretation into them.

‘The decisive moment is not a dramatic climax, but a visual one: the result is not a story but a picture’ – Szarkowski, 2007, p.5

Szarkowski’s assertion about the decisive moment is a good starting point as with most of his book [1]. Like most people, my early photography was snapping pictures of whatever was in front of me without any planning or understanding of what I was trying to get across. Storytelling or a visual climax that has the view asking questions about what the photograph might mean, didn’t enter my ‘process’ of taking the picture. As I progressed in confidence, my thoughts moved towards creating something that was pleasing to look at, which in turn drove me to photographing landscapes. However, I was still trying to simply please the viewer rather than present them with a photograph that revealed the subject or, heaven forbid told a story. The idea of some order to the photograph that includes visual and contextual balance along with inviting the viewer to create their own accompanying narrative, appeals to me. However, I also see value in the counter-argument that the decisive moment does not describe the events prior to, or following the moment the image is made. To truly reveal what is going on with the passing of time needs more context, such as in the work of Graham and Luski [2]. While I admire the counters to the decisive moment, I am more interested in my own interpretation of the concept as defined by Cartier-Bresson. As someone who has struggled to shoot this way, I wanted to shoot this assignment in tribute to it, as I believe it still has relevance today in its challenging the viewer to internally narrate what they see.

There were a two elements of research during Project 3 [2] that captured my interest. The first being the admission by Cartier-Bresson that luck played a major part in one of his iconic decisive moments and the idea contrasted with really looking at the scene. The second being the idea that a decisive moment cannot be forced or brought into being by the photographer. I concluded from this that a plan is not a bad thing, thinking in particular about Cartier-Bresson’s Hyères, 1932 [3] but that in preparation for a photographs like that, the photographer has some element of control over when the decisive moment occurs. In addition, one can work the subjects in the frame to gain the best chance of capturing the moment, by altering perspective or viewpoint and waiting for the rest of the picture to present itself. The quotation from his book, The Decisive Moment places a great importance on the decision by the photographer to take the picture in addition to seeing the moment itself either instantaneously occurring or evolving in front of them.

Why have I struggled with this?

Simply put, my original interpretation of the decisive moment was being able to observe, identify and capture the moment instinctively and with alacrity. Street photography that involves people forming part of the subject matter has always been a difficulty to me, owing in part to my lack of confidence in shooting discreet pictures of people. However, knowing that I can set some parameters to the image before the moment occurs, gave me the inspiration to try street photography again during a recent trip to London. An example of my work from that trip can be seen below.

Southbank, London 2019 by Richard Fletcher

I saw the man sat on one of the brightly coloured benches outside the Southbank Centre with his dog. It was clear from his behaviour that he was waiting for someone to arrive. I was shooting with my Leica M6 with a 50mm lens mounted, which offers a very discreet shooting experience because of its quiet shutter but having a focal length that required me to be close to the subject. I positioned myself where I could see the dog clearly and some contextual background in the canopies and the pathway that had many people walking along. To be even more discreet, I asked my wife to sit just outside the frame on the right hand side so that it looked like I was photographing her. When the woman appeared and greeted the dog, I shot two frames. The luck element in this composition was the casual observer behind the subjects, which for me makes for the decisive moment. My input to it was different to previous street photography experiences where I wandered around trying to will a picture into being by observation only. My lack of speed with a camera as old as the Leica meant that I had previously missed many intended decisive moments. Armed with this approach, I began researching the photographers that inspire me.

My Research

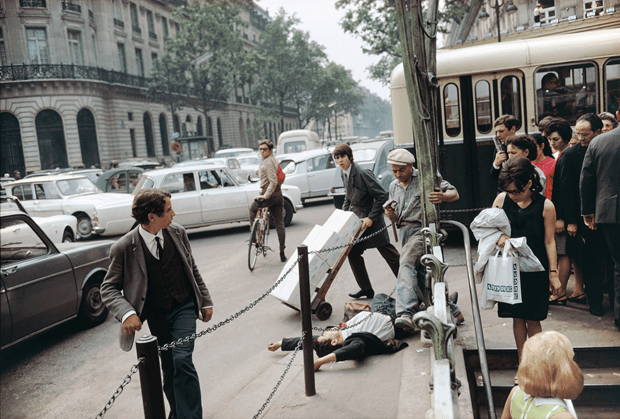

I’ve previously stated that the work of Joel Meyerowitz has inspired me a great deal in my photography over recent years. My favourite photograph in any genre is one of his early colour street photographs that is a great example of the decisive moment (below). This fleeting moment with its huge visual impact and potential for narrative captures my attention every time I look at it. It’s not a surprise that his body of work contains many classical decisive moments.

Paris, France, 1967 by Joel Meyerowitz (from Taking My Time, Phaidon)

“A young man lies on the sidewalk with his arms outstretched. A workman with a hammer casually steps over his fallen body. A crowd stands at the entrance to the métro, stunned by curiosity into inaction. A cyclist and a pedestrian each turn over their shoulders to catch a last glimpse, while around them the traffic glides by. Which is the greater drama of life in the city: the fictitious clash between two figures that is implied, or the indifference of the one to the other that is actual? A photograph allows such contradictions to exist in everyday life; more than that, it encourages them. Photography is about being exquisitely present.” – Joel Meyerowitz talking about Paris, 1967 in 2014[4]

While I wanted to pay tribute to the decisive moment and this image in particular, I wanted to look at how the photographer’s decision can be brought directly into the image, using either subtle or exaggerated ‘working of the subject’ within the composition. Reviewing Meyerowitz collective works book [5], one photograph struck me as an example of the photographer’s ‘decisive moment’. This image can be seen below.

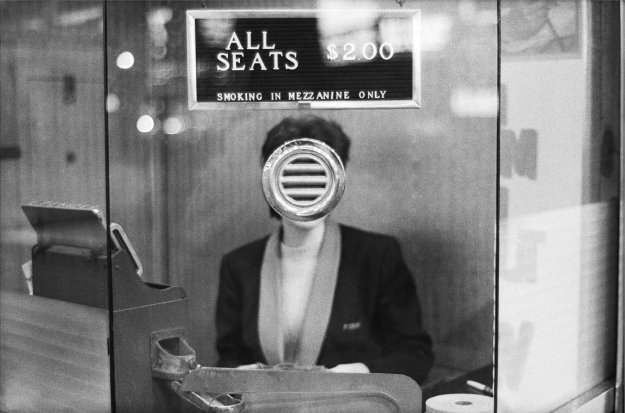

New York City, 1963 by Joel Meyerowitz

Here we are a lady in a ticket booth looking toward the photographer but her face is completely obscured by the microphone grille in the glass in front of her. She is not in the plane of focus, instead Meyerowitz draws the attention to the glass screen and the information on the sign attached to it. My initial reaction was to question whether it’s a decisive moment at all, but noticed that I was narrating what was occurring in the image. I then realised that the moment is the photographer’s as a booth like this is intended for as brief an engagement as possible. Meyerowitz had to see the juxtaposition of the woman and the grille, the frame created by the glass and the balance between in focus and out of focus elements, all presumably before holding up the line to the booth or being noticed by the subject herself. For me, a decisive moment driven by perspective and deliberate obscuring of the main subject both spatially and in focally.

I recently had the opportunity to view exhibitions by Diane Arbus and Martin Parr; two photographers with very different styles. In both collections, I saw images that follow similar lines to the above, placing the subject either in partial or full obscurity while having the impact of a fleeting moment. The first, from Arbus’ exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in Southbank, London is a shot of a scene from the motion picture Baby Doll taken in 1956 in New York.

The scene is a a kiss, but the two people in the shot are almost completely lost in the way the photograph was exposed. The lighting in the film was clearly to emphasise the female character’s eyes, which reminded me of my second assignment [6], but Arbus also underexposed the photograph in a way that preserved the few highlights while the boundaries of the composition are lost in darkening shadow. The effect is that the image clearly shows the fleeting moment of the kiss in the linear timeline of the film, but Arbus creates the visual impact by obscuring any detail or distraction from the frame. I don’t personally know the film, so the context of the scene invites speculation as opposed to the picture telling a story in its own right.

By contrast, the image using this approach that struck me from Martin Parr’s exhibition at The National Portrait Gallery [7] is a fun affair. I’m a fan of Parr’s lighthearted perspective on life and social class, brought to life in almost over-saturated pictures. They remind me of holiday snaps at first glance, but Parr’s technique is to distract from clear photographic skill, leaving the subjects and settings to speak for themselves. For his collection A Day at the Races, Parr took the photograph below using obscurity to emphasise the moment.

The Derby, Epsom, Surrey, England 2004 by Martin Parr

In this photograph, the conversation between the two main subjects is clearly cordial, but that’s about all we can see. The man’s face is almost completely obscured by the hat and drink, which, along with the couple in them background set the context of the moment. Unlike Arbus’ image, with this photograph Parr doesn’t take things too seriously and as with much of his work, the use of flash and the heavy saturation tend to polarise the public and critics alike. However, the element of fun in this composition is something I intend to introduce to my collection for this assignment.

The final photographer I researched in preparation of this assignment was Garry Winogrand. Winogrand was a photographer who didn’t approach his work with over-complexity or the need for a narrative. In an interview towards the end of his life [8] he said

“A picture is about what’s photographed and how that exists in the photograph – so that’s what we’re talking about. What can happen in a frame? Because photographing something changes it. It’s interesting, I don’t have to have any storytelling responsibility to what I’m photographing. I have a responsibility to describe well.”

What he was saying here is that a subject undergoes a change from the perspective of the viewer and the photographer is responsible for how it is presented, not what it might mean; very much in line with the devolved sentiments around the decisive moment.

While he photographed many subjects, he was known for challenging compositions that often caused controversy, for example his photograph of a young mixed-race couple carrying chimpanzees at Central Park Zoo [9]. The photograph was has a naturally balanced composition with the couple merely walking along, completely relaxed. It was interpreted by a shocked America as a suggestion of what might happen if a mixed race couple were to have children. Winogrand saw the likely problem at the time but asserted no responsibility for how others would interpret it. The same drawing of conclusions beyond what is in the photograph as experienced in a decisive moment.

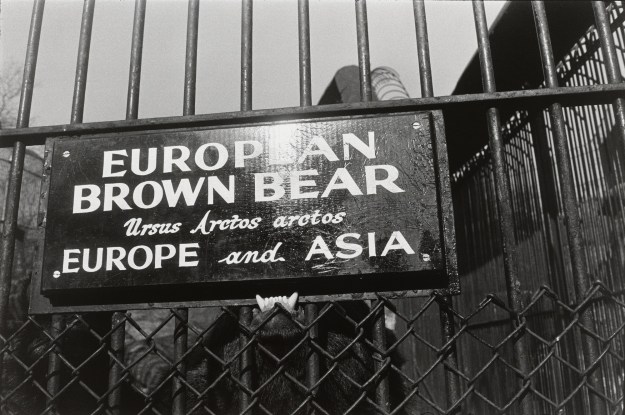

He took his documentary style of wanting to see how things looked then photographed [8] through a number of subject matters. One of the first of Winogrand’s images that I saw was from his collection The Animals (below)

Central Park Zoo, New York City, 1962 by Garry Winogrand

Here we see a simple composition of a sign describing the occupant of the enclosure. Only on closer inspection, we can see the moment where the bear’s jaw, its face obscured by the sign. The image is devoid of clutter and the subjects within the frame all relate to each other. However, the brief moment of contact with bear indicates captivity, which can be interpreted a variety of different ways. The convergence of the teeth and the cage sign occurs at the decisive moment, but the visual climax is made by how much of the bear we do not actually see.

My Idea

The works of these 4 photographers are different from each other in so many ways, but the common thread of these images is that they are a series of decisive moments, driven more by the photographer’s decision to release the shutter more than a specific action taking place. Each has a planned feel to it, with the subject being worked to an extent before the moment that the photographer is trying to catch is committed as an image. The missing elements caused by obscuring part of the subject causes the stand-alone visual climax that Swarkowski was referring to as well as promoting the narrative that might the reason behind the photograph. Each photographer went about it in different ways and with different styles but reached the same outcome.

My series of photographs will be on the theme of unconventional perspectives on a moment that I decide to shoot, using some playful juxtaposition of subjects being partially obscured.

Some Thoughts on Styles and Subjects

My first requirement was to try to emulate Parr’s sense of fun. The subject must be in plain sight but not necessarily obvious as with Winogrand’s bear and there must be some context to where the subjects are within the frame. Decisive moment may not tell a story, but the image must be in balance. Street scenes were the obvious choice as there are people and situations that they find themselves in, no matter how mundane. As well as partially obscured faces, I was looking for an obvious human form, but only part visible to the viewer to create a disembodiment, e.g limbs without bodies, floating heads etc. The decisive moment still needed to be captured too, so staging images beyond the level that Cartier-Bresson did was something I would not do.

I also wanted the images to be colour to connect with Parr’s style, but although dominant, vibrant colours would be an option, I did not want to limit the set by copying Parr. Another consideration was a recent EYV video conference where the question of ‘what makes a collection?’ was discussed. Among ideas such as similarity of subject, environment and light, we discussed the use of aspect ratio and adopting either ‘all colour’ or ‘all black and white’. The latter could be an option for this assignment but I concluded quickly that it was a lazy way of connecting the images together. During the days of black and white film, there was no choice in the matter but with colour, the opportunities to link bold colours or subtle background tones were open to me.

The Images

- Photo 1

- Photo 2

- Photo 3

- Photo 4

- Photo 5

- Photo 6

Photo 1

It occurred to me that the decisive moment didn’t have to be something organic, that it could also include repeating, fleeting moments as with Arbus’ Baby Doll image which was itself a frame on a piece of film. I spotted this mobile phone shot covered in scaffolding and the rolling neon sign promising repairs inside. The irony reminded me of Parr’s recent collection ‘Britain at the time of Brexit’ where confusion is represented both literally and metaphorically.

Photo 2

Walking around Bristol, I encountered people wearing huge billboards on their backs, which obscured all but their limbs from some angles. I followed these on their mission to offer cheap bus rides to passing visitors. It was difficult to shoot as they would quickly turn to look out for the rest of their group who had scattered around the square.

Photo 3

A well known busker in Bristol, Junkoactive Wasteman captured the attention of some climate change campaigners. This shot was fairly straight forward in that once the dustbin lid cymbal was positioned with respect to the subject, it was a matter of waiting for the dancing.

Photo 4

I noticed two postal workers carrying a parcel to their van and noticed the brief moment where they were completely obscured. I wanted this to be a simple composition, so positioned the van to dominate the frame with the subject on the right hand third line.

Photo 5

A coffee shop in Malvern that piles the cups high. I noticed that the only member of staff who regularly made coffee was the tallest one. I shot several photographs trying to capture him using the milk steamer. The decisive moment I ended up with was him reaching for a cup from the stack.

Photo 6

Is saw this scene unfold as the pavement narrows near where the couple had parked their car. In trying to navigate through the people, I spotted the dog’s head above the line of the car boot. I shot two frames as the moment passed very quickly. As with Cartier-Bresson’s luck, only when I downloaded to the computer did I notice the family reflected in the glass of the car behind.

Reflection

This assignment was a huge challenge for a photographer not comfortable with street shooting. When researching the decisive moment for Project 3, I decided that for this assignment I would try to make things easier for myself. I wanted to work with the concept as I believe it to be an important cornerstone to photography revealing a subject as it is impacted by what is happening around it. However, I wanted to show that the decisive moment was as much about the decision to release the shutter as the moment itself, something that Cartier-Bresson mentioned in the quote earlier, but seemingly left out of many analyses of his work. The more I looked at this element of the decisive moment, the more I realised that it can be found everywhere. The irony here is that in consciously adding the photographer’s influence in this way, I actually made the whole assignment much harder. I’ve never been an instinctive photographer, preferring instead to carefully compose and choose the look and feel of the image before pressing the shutter button. There is no room for it in this work, which pushed me further than previous exercises and assignments had done.

For me, the strongest image is Photo 6 as it combines my viewpoint and the decisive moment itself in one photograph. The equipment frustrations that I had all the way through this work was more evident in this shot than the others. I have perfect street cameras in the Leicas but they are both film and my skills with them are not as advanced as when using my DLSRs. However, in the event that the subject has seen me raise my camera to my eye I may as well be pointing a Howitzer at them. If they hadn’t seen me, the noise from the mirror slap is enough to attract attention. In the case of Photo 6, I managed to get all elements to work together. I noticed that one of the elements that connects the images together are the colours red and green. In some cases, they are dominant and in others subtle. The only photograph that doesn’t follow the theme is Photo 1. I like the irony of the composition which isn’t part of the rest of the set, but don’t feel like this image is as strong as the others. However, given the difficulty that I had shooting for this assignment, I elected to include Photo 1 as it points to the in-organic decisive moment where the others rely on a brief slice of time related to life.

Overall, I am happy with the collection. Each image achieves the obscured feel that the photographers worked with, as well as a decisive moment playing out in front of the lens. I believe the decision to shoot is strong in each, which is what I set out to explain with the collection. I would improve the strength of the collection by seeking to improve my street photography, which is largely through building confidence with practice.

References

[1] Szarkowski, J, 2007 edition, “The Photographer’s Eye”, The Museum of Modern Art.

[2] Fletcher, R, 2019, “Project 3 – What Matters is to Look”, http://www.richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog, accessed March 2019

[3] Goldschmidt, M, 2014, Artist Entry, Tate Museum, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/cartier-bresson-hyeres-france-p13112, accessed March 2019

[4] Phaidon Publishing, 2014, “Why Joel Meyerowitz thinks this is his best photo”, https://uk.phaidon.com/agenda/photography/articles/2014/september/03/why-joel-meyerowitz-thinks-this-is-his-best-photo/, accessed March 2019

[5] Meyerowitz, J, 2012, “Taking my Time”, Phaidon Publishing

[6] Fletcher R, 2019, “Assignment 3 – Collecting”, http://www.richardfletcherphotography.photo.blog, accessed March 2019

[7] Parr, M, 2019, “Only Human – Exhibition Catalogue, National Portrait Gallery

[8] Moyers, B, 1982, “Garry Winogrand is interviewed by Bill Moyers, https://www.americansuburbx.com/2009/06/interview-garry-winogrand-excerpts-with.html, accessed March 2019

[9] Winogrand G, 1967, “About a Photograph”, https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/7084, accessed March 2019