Introduction – what we know so far

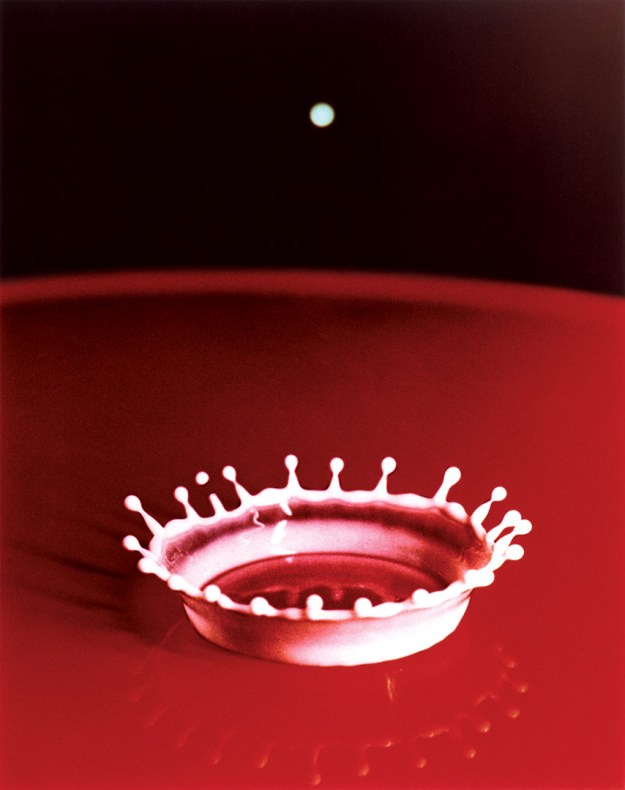

With the completion of The Frozen Moment, it’s clear that photography gives us the ability to reveal what the human eye is not able to isolate or retain. The work of Muybridge, Worthington and Edgerton further reveals the beauty in nature that is happening all around us but is largely invisible. During our recent video conference, Rob Bloomfield challenged us to look for the key elements in the first of the assessment criteria for this course in Edgerton’s Milk Drop Coronet, 1957 (below).

Milk Drop Coronet, 1957 by Harold Edgerton

The criterion in question was as follows:

- Demonstration of Technical and Visual Skills, which breaks down into

- Materials – this could cover any element brought into making the photograph, such as light, equipment, props etc.

- Techniques – what was used to make the image?

- Observational skills – seeing the elements that make up the photograph as it evolves

- Awareness – similar to observational skills, but more being aware of the context, the moments leading up to the decision to make the photograph

- Design and compositional skills – how the photograph was executed.

When we were discussing this, my initial thought was that one would be unlikely to look at every image with these criteria in mind as thusfar, I’ve been considering the impact an image has on me personally and how that might work creatively. However, I’ve come to realise that this gives our consideration of a photograph a simple structure to challenge the way we might think about the image. Practicing using these simple titles may help understand the quality of a photograph.

With regard to Milk Drop Coronet, the obvious materials include milk, strobes and dye, but the technique was the ground-breaking use of strobes combined with the fastest shutter cameras available. When we consider awareness and observation, it is here that the creative connection is made. Edgerton was an engineer who began photographing the everyday. His knowledge that the surface tension of the milk; the effect of the connection of the molecules at the boundary between the milk and air above it, would be disturbed by the falling droplet. What he wanted to observe was how the energy from the drop dispersed as it impacted the surface. What he revealed was the beauty of this natural physics in action. His compositional skill with this image is in the cleanness of the the background and placing of the next falling drop above the coronet. It is a stunning image, both technically and aesthetically.

For the Durational Space

In this Project, we see photography used to reveal time instead of stopping it. Although my early photographs as a child exhibited motion blur for all the wrong reasons, the concept of using long exposure to capture the passing of time through a moving subject is something I am more than familiar with.

Capa’s photographs from Omaha beach are, as we know a combination of a number of elements that occurred deliberately and accidentally [1]. Capa set out to show the hell that is war by observing the emotion in a situation rather than trying to be a part of it.

“You cannot photograph war, because it is largely an emotion. He [Capa] did photograph that emotion by shooting beside it. He could show the horror of a whole people in the face of a child” – John Steinbeck

Capa’s creative vision in being an observer to war’s emotion is complimented in the Omaha beach photographs by other factors. The film was botched during development which vastly reduced the number of usable negatives from the roll as well as increasing the drama of each through larger grain and blurring. The solider in the image that has come to be called ‘The Face in the Surf” was later identified and tracked down. Almost immediately after the photograph was taken, the soldier was injured and Capa found himself helping him onto the beach so that he could be treated. In a way, Face in the Surf was a slice of time captured when the soldier was advancing on the enemy with the steely, committed expression on his face. That slice of time, however was longer than the works examined in Project 1, starting with Capa’s observational awareness and ending with the soldier being shot.

Face in the Surf, 1944 – © Robert Capa

For me, the use of movement in an image describes something that can only be appreciated during more than a passing glance. What is clear in Capa’s famous image is that the blurred subjects in the foreground and background make one linger on the image long enough to observe the hell of war that Capa was witnessing.

With Hiroshi Sugimoto’s work Theatres, photographer uses time to completely remove traces of activity from the images. Opening the shutter when the film starts and leaving until the final credits, the screen is completely blank; all traces of the movie failing to register on the photographic film. In Sugimoto sought to use the static subjects in the image to frame the void of empty space, which reveals the beauty of the old theatre buildings themselves. The effect of the movie providing slow, soft light and the absence of any people in the image leads the eye around the detail of Sugimoto’s framed emptiness.

Carpenter Center, 1993 by Hiroshi Sugimoto [2]

World Trade Center, 1997 by Hiroshi Sugimoto [2]

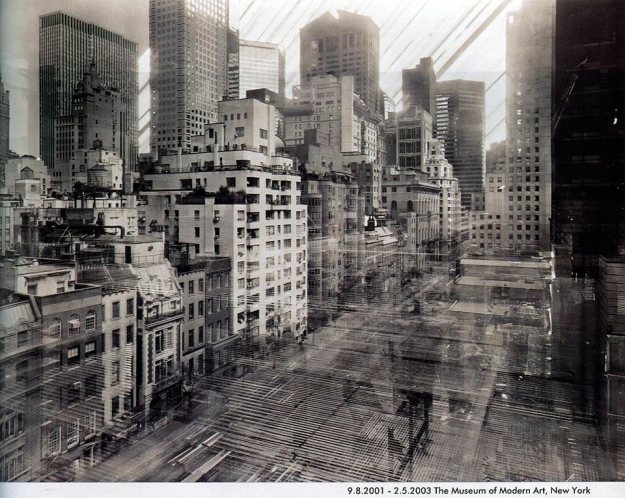

MoMA, 2001 to 2003 by Michael Wesley

For me though, his more interesting work is far less grand. His shot of a vase of flowers dying slowly over time from the series Still Lives, shows the power of this technique []. Here, the viewer can clearly see the flowers in their prime gradually moving downwards as they decay and drop petals on the table. This image evokes a sadness related to the loss of the flowers but also how time can be compressed into a single, seemingly fleeting frame that is itself only looked at briefly.

Still Lives, 2013 by Michael Wesley

My Own Work on Durational Space

As I stated previously, I am no stranger to the use of long exposure or the addition of accidental technique to achieve motion or drama in an image. However, unlike Sugimoto, I’ve not previously envisioned the subject and then decided how to shoot it to achieve the aesthetic that I want. Perhaps the most common of subjects for me have been photographing triathlon events and waterfalls, both needing movement to be revealed in order to make them interesting. I have included two examples here.

On Your Right, 2016 by Richard Fletcher

The first is a shot I took at a race in 2016. My friend is about to pass a cyclist much to his surprise and probably frustration. I’d been practicing panning the camera with a slow shutter speed to include the movement in cycling as without that, the result can be very static. The sense of speed of both sets of wheels in this shot is emphasised by the indecipherable writing on the rims of the red bike. Her expression of pure focus on the job in hand is offset by the guy looking back at her which suggests that he is unsettled. The background and foreground detail is largely lost, even though the spectators can be seen clearly enough.

West Burton Falls, 2017. by Richard Fletcher

The second photograph is one that I shot with a pinhole camera, which I’d not used before. I was at shooting West Burton Falls in North Yorkshire with my DSLR and the technique was all about capturing the movement of the water over the falls themselves. When it came to this camera, the extremely small aperture of f132 and no control other than choice of film ISO and shutter ‘speed’, a long exposure with this camera would be all I could really achieve. What I failed to appreciate was that film has a non-linearity of sensitivity decay called Reciprocity Failure. This is the way that the film gradually loses its light sensitivity over the duration that it is exposed, which is not a problem at typical speeds such as 1/30th. In fact, when the exposure slows to over 1s the reciprocity failure value for that film stock means an even longer exposure to get the same amount on the film, e.g. 1s might instead be 2 or even 4 seconds to get the same equivalent exposure. I had not taken this into account with my 15 second exposure in this photograph. The resulting happy accident was an underexposed shot of the whole distance to the falls from my position, which in reality was only about 50m away. Pinhole cameras tend to have substantial light roll-off from all but the centre region of the image so what shouldn’t have worked at all, ended up being a softly lit, glass-like waterfall with almost no sharp details to distract from it.

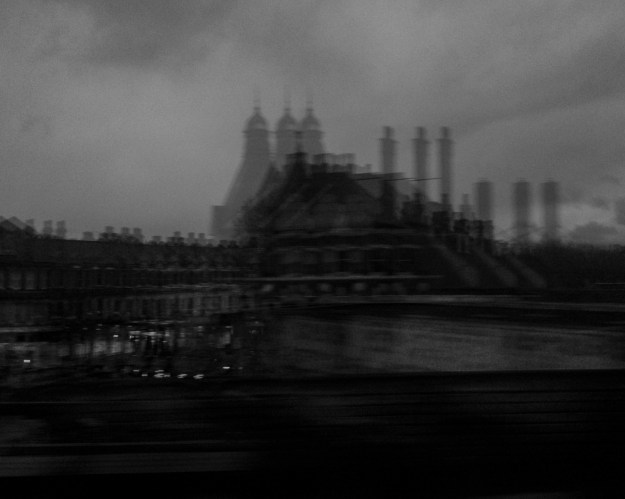

In concluding the study for this Project, I recently visited London for a short break. On the overland train back to our hotel, I noticed the way that perspective of the lit skyline changed as the train moved past. In a similar way to Maarten Vanvolsem [4], I turned to my smartphone that has an app that creates a pseudo slow shutter speed. It achieves long speeds by taking multiple shorter speed shots of say 1/2 second and overlays them. For the two images below I pressed the phone to the train window to reduce internal reflections from the glass and shot the skyline with exposures of 3 to 5 seconds.

From a Train, 2019 by Richard Fletcher

From a Train 2, 2019 by Richard Fletcher

The first shot of the Brixton skyline on the way into the station shows the effect of layering, which for some reason the phone did not stitch the three images together properly. The second shows the skyline crossing the river, with the motion of the train, its motion and the window glass distorting the cranes on the horizon.

In conclusion, the durational space takes us away from the stationary. The viewer looks at the image for more than simple sharpness and lack of blur or noise and instead embraces the feeling of time passing. This passage of time is much like the ‘moment’ that we achieve with fast shutter speeds, but instead of revealing what we don’t see, it reveals what we might not have noticed. In the case of Capa, it emphasises the emotion and terror or the war. In Sugimoto’s work, we are directly to consider the unnoticed and the idea behind the subject and its place in the composition. I mean, when was the last time we noticed the interior of a cinema during a showing of a film? Wesley’s work draws our attention to progression over time, from the simple act of a plant dying to the major renovation of a museum building. Finally, the brain’s ability to see the movement in a still image means too that the way the photograph was shot could also be abstract as with Vanvolsem’s Contraction of Movement image [4].

References

[1]. Wiess, H, 2018, Visual Culture article, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-photographer-robert-capa-risked-capture-d-day-images-lost, accessed February 2019

[2] Sugimoto, M, https://www.sugimotohiroshi.com, accessed February 2019

[3] Gramovich, M, 2015, Time Shows, Ultra-long exposures in the work of Michael Wesley, https://birdinflight.com/inspiration/experience/time-shows-ultra-long-exposure-in-works-of-michael-wesely.html, accessed February 2019

[4] OCA, 2018, Photography 1 – Expressing your Vision Course Notes