Initial Thoughts and Research

Anyone of middle age can remember their early encounters with photography in the film age. Most cameras accessible to young boys like me in the 1970s had limited control; there was basic automatic exposure and if one was lucky, a couple of fixes shutter speeds. Like many children of my age, I didn’t understand shutter speed, so automatic was my ‘mode’ of choice. In not understanding the part that time plays in photography, my early efforts often had motion blur, caused either by the subject moving or a shaky hand. These accidents were met instantly with a sulk, disposal and the immediate need to find more film to put in my camera.

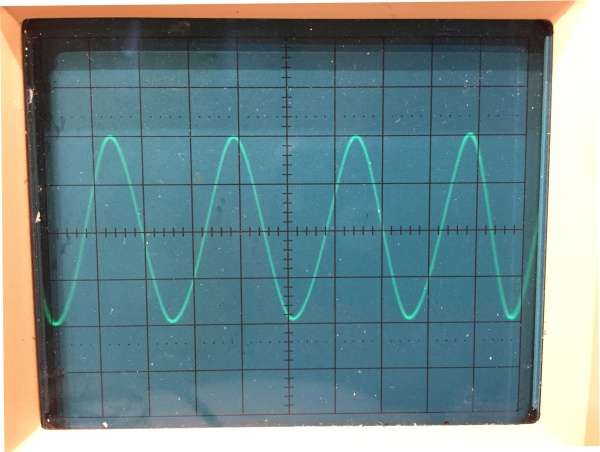

My first real introduction to the importance of time, or shutter speed was when I was an apprentice engineer. We used oscilloscope machines to measure waveforms in our electronic circuits, which were displayed on a cathode ray tube screen; an old television essentially. The line scan of the ‘scope was rapidly repeated in the screen so that the trace remain visible to the eye, but in fact each trace was a fragment of time during which the signal being measured was changing. If the signal changed in a repeatable way, as in a sinusoidal wave (Photo 1), the trace would look like it was standing still on the screen.

Photo 1 – Sinusoidal waveform on an old analogue oscilloscope (image from EDN.com)

Nevertheless, the only way the user could preserve that image indefinitely was to take a photograph. In those days, the system of choice was a polaroid pack film camera which would take a single instant picture at a fixed focal length determined by the end of its hood (Photo 2).

Photo 2 – Polaroid Oscilloscope Camera (source: Rabinal on Flickr)

The film had a very high ISO of 3000 so that the dimly lit screen could be exposed properly. What I came to learn though was the single, fixed shutter speed of the camera was still fairly slow (of order 1/30th second), so the trace needed to be stable to get a ‘sharp’ image. If the circuit being tested changed the trace in any way during the time the shutter was open, the image would have a ghost trace superimposed on it. Being exuberant teenagers, my colleagues and I used the camera for shooting other subjects in the camera’s focal plane and while mercifully none of these prints survive, I recall us shooting posed portraits, where everything was held as still as possible and more candid shots with movement and anything else that could be captured in the small frame.

“There is a pleasure and beauty in this fragmenting of time that had little to do with what was happening. It had to do, rather, with seeing the momentary pattern of lines and shapes that had been previously concealed within the flux of movement” – Szarkowski, The Photographer’s Eye, 2018 (reprint)

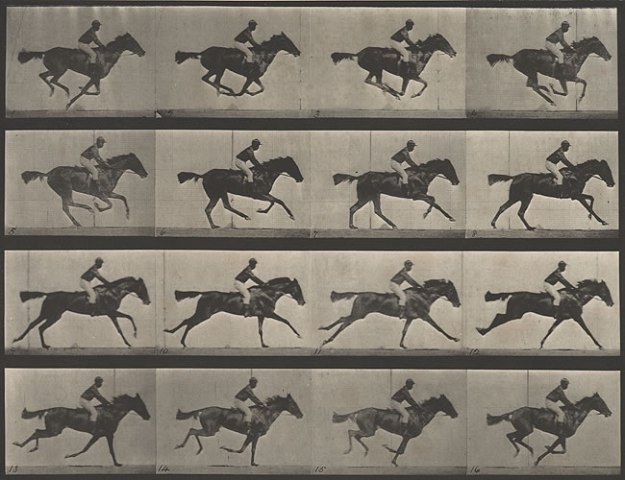

When I read this quote in Szarkowski’s book[1], I immediately appreciated what he was saying. Photography was initially a clinical capturing of a subject or scene, which was very different from classical painting where the artist had to represent their interpretation of something witnessed. The struggle for photography to establish itself in its infancy as an art form is for me, vindicated by the fact that selecting a slice of real time is possible because of the technical capability that was initially rejected by the art world. In reviewing Duchamp’s famous painting “Nude Descending a Staircase No 2” [2], we could be forgiven that this cubist depiction of a nude figure represented in a time-lapse style was an influence for photographers of the time.

Nude Descending a Staircase No2., Marcel Duchamp, 1912 [*]

Horse in Motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1872

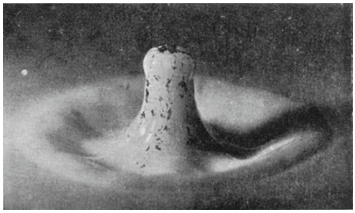

In the late 1920s, A.M. Worthington FRS built upon Muybridge’s work by using the ever advancing shutter technology to capture images of splashes and droplets in his study of fluid-dynamics. Worthington still found that shutters were too slow and so, turned to a combination of very high sensitivity photographic plates and a short duration ‘spark’ timed to illuminate the subject at the point of impact. The subsequent images are very grainy and inconsistently lit, but of little consequence as Worthington’s work was more about the practical understanding of the effect of collision and dispersal of energy[4] than creating anything artistic.

The Splash of a Droplow Fall (no.13), A.M. Worthington from his book “A Study of Splashes”, 1908

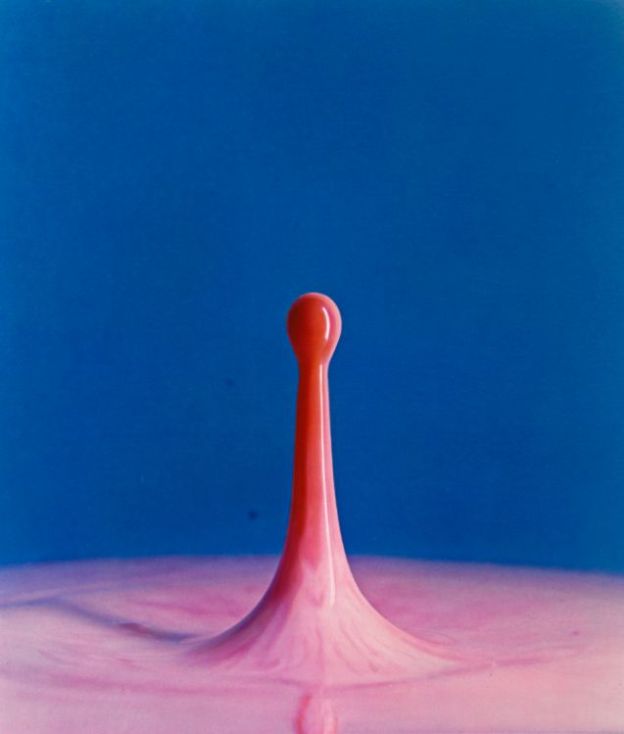

However, his application of the technical advancements of cameras led others to capture beauty in the laws of physics. In seeking the beauty that Szarkowski refers to, we start by looking at the work of Harold Edgerton. During a scientific career, Edgerton pioneered the use of reliable, high speed strobe lights to act as the ultra-fast shutter (of order 1/1,000,000th second[5]. Now photographic detail and quality of reproduction could capture microsecond slices of time and reveal the beauty of the seemingly ordinary.

Dye Drop Into Milk, Harold Edgerton, 1960. Reproduced from Huxley-Parlour’s catalogue of works

The image above shows one of Edgerton’s photographs similar to Worthington’s work. The use of colour enhances the subtle mixing of the dye drop as it impacts the milk and captures the beauty of the physics of nature.

These three photographers are famous for their work in advancing technical understanding rather than art, but their photographs taken on an artistic appeal because of their connection with the natural world, usually missed in real-time.

My Conclusions

In researching this topic, I’ve quickly come to realise the ability to extract a small unit of time from the natural course of events is something that photography can exclusively claim for itself. The work of Muybridge, Worthington and Edgerton appeals to the engineer in me as with those early days in my career with that ‘scope camera, my intent was to capture something that I knew to be fleeting but was being made static be the oscilloscope itself. Those repeated fleeting moments that I was trying to capture had the same properties as the subjects they were trying to capture, only their efforts required grabbing the moment as a one off. As I’ve progressed as a photographer, I’ve naturally understood shutter speed, its place in achieving an exposure and how to use it to capture instantaneous and evolving slices of time. However, I hadn’t appreciated until now the use of it in an artistic sense. Taking DiCorcia’s work as an example, the fleeting moments captured in heads are all different, yet the same. The beauty for me is the story of which these moments are a part; ‘Where are they going?’, ‘What are they experiencing on their journey?’. The subjects were all walking through Times Square, going about their lives in a variety of different ways, yet all having the fact that they were ‘trapped’ in the same way in common. When I saw an exhibition of ‘Heads’ at the Hepworth Gallery, Wakefield in 2014, I was struck by how powerful the private nature of these moments were and how DiCorcia had arranged the lighting to isolate the subject from the environment as if they were experiencing life by themselves. I’m not surprised that DiCorcia got into legal trouble about the series as we believe our daily lives are our own property. By capturing a slice of that property without discussion or permission, we breach that concept of ownership and privacy.

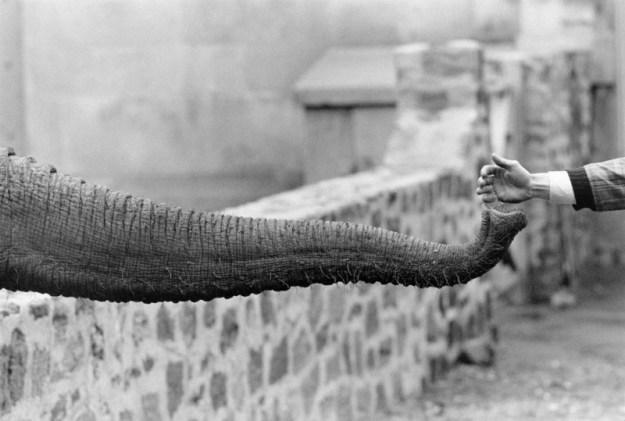

With the ‘pattern of life’ quality of DiCorcia’s work, I concluded that freezing a slice of time isn’t simply a mechanism used to be clever or scientific. In terms of art, the traction of a moment further adds to the mystery of the story. With this in mind, I went back to Szarkowski’s book [1] and looked through the collection of photographs to underline my point. The one that struck me because of its subtle movement was an untitled picture by Garry Winogrand. The image is of an elephant being fed by hand.

‘Untitled’, Garry Winogrand, 1963 (from The Photographer’s Eye)

The apparent movement is not obvious, but this is the point following the offer of food and before the elephant feeds. This photograph is made more intriguing by the exclusion of most of both subjects from the frame. Who is the person feeding the elephant? Could be a zoo-keeper, but his jacket looks more sixties fashion than uniform. Was he even supposed to be feeding the animals? This photograph explains much but also leaves the viewer with questions, made possible by the frozen moment and interesting composition used together.

References

[1] Szarkowski, J, “The Photographer’s Eye”, MomA reprint 2018

[2] Chadwick, S, “Introduction to Dada (page 2)”, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/wwi-dada/dada1/a/marcel-duchamp-nude-descending-a-staircase-no-2, accessed January 2019

[3] Herbert, Alan, “Exhibition Notes”, University of Texas, https://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/windows/southeast/eadweard_muybridge.html, accessed January 2019

[4] Worthington, A.M, “A Study of Splashes”, 1908

[5] Editorial, Harold Edgerton, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Harold-Edgerton, accessed January 2019