The Brief

Find a scene that has depth. From a fixed position, take a sequence of five or six shots at different focal lengths without changing your viewpoint. (You might want to use the specific focal length indicated on the lens barrel). As you page through the shots on the preview screen if feels as though you are moving through the scene.

Research

The course notes make reference to Ridley’ Scott’s Blade Runner, which is one of my favourite science fiction films. I have been a fan in large part because of the close relationship between what could be real science or engineering, and the fiction that the film envelops it in. Growing up, the predictions of this century were all around voice control, self-driving flying cars and artificial intelligence. While cars don’t fly, the rest is pretty much here including the ability to resolve images in ultra-high resolution. Deckard’s scanner is almost real, only separated from reality by the 3D exploration of a 2D image. We can, however forgive that level of artistic licence. In reviewing Google’s gigapixel work, it’s clear that the technology is hugely impressive but the real interest is in what the extreme zoom capability reveals that could be missed from the more distant viewpoint. The painting that caught my eye was Vermeer’s “Girl with the Pearl Earring”, a very famous, and often copied image. I’ve always been superficially impressed by it, but with the gigapixel, the ability to explore the micro detail of the painting gave me a new appreciation of it.

The original canvass is only 17.5 inches by 15 inches in size, which makes the detail of the painting closeup extraordinary. Looking at the eyeball itself, we can see subtle shadowing near the lower eyelid and both colour and texture in the cornea. Vermeer painted this with attention to these details as well as the subtle highlight and shadow detail around the face and was known to use a camera obscure to accurately assess the way that light was falling on the subject [2]. To think he did this in the 17th Century with whatever light was available and his own imagination, I find remarkable. Except for the fact that there are many painters of this era who were achieve similar feats. What surprised me is how the technology of the modern digital camera provides us with these insights.

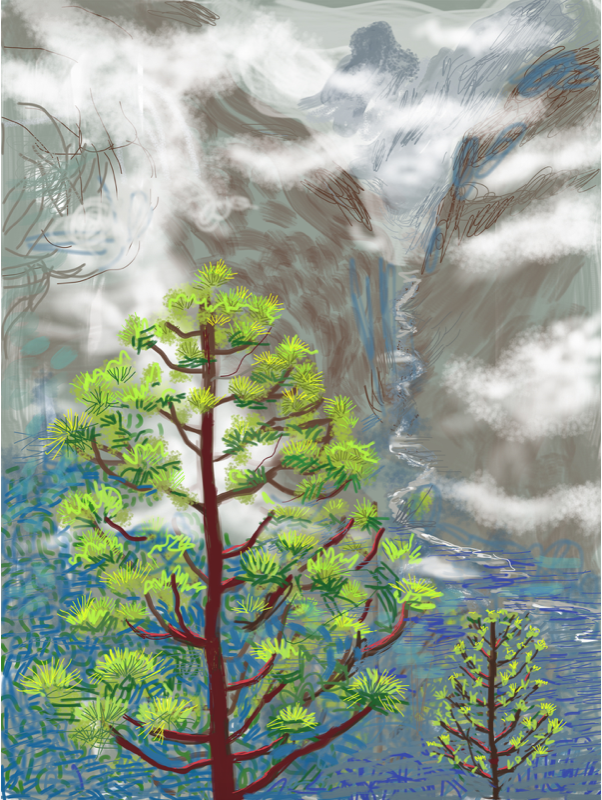

This reminded me of one of my favourite artists, David Hockney who presented an exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy of Art in 2012 [1]. I went to this exhibition and the paintings that struck me the most were a series called Yosemite. Hockney had created artworks that were 365.8 cm by 274.3 cm made up from an assembly of 6 prints made on dibond paper. This in itself wasn’t the unusual aspect, because Hockney had ‘painted’ each panel on an Apple iPad. In the reverse situation to Deckard’s extreme blow-up of a small print, Hockney achieved a huge painting by working at the micro level first. The effects were a series of beautiful paintings as digital prints as shown below.

Yosemite 1, David Hockney, 2011

My plan

I have a mix of lenses for my DSLRs that include fixed focal length, or prime lenses, wide angle and telephoto zoom lenses. For this exercise I decided to use the Nikon 70 to 200mm f2.8 lens as it offers the longest range of focal lengths and has very high quality glass elements. For the location, I chose Great Malvern’s railway station platform, which is a typical example found in a Victorian town.

When I arrived I realised, quite reasonably that the railway station did not allow tripods. For my set, I was going to have to hand hold so I went with the following settings.

- Aperture Priority set at f11.

- ISO200.

- Manual focus – to begin with, I did not want to re-focus and re-meter between shots. I picked the coffee sign as the point of focus.

- Setting 70, 85, 105, 135 and 200mm as per the lens barrel markings.

My Images

- P1 (70mm @ f11)

- P2 (85mm @ f11)

- P3 (105mm @ f11)

- P4 (135mm @ f11)

- P5 (200mm @ f11)

The first noticeable issue is that reading the focal length markings on such a large lens while handheld is a major challenge. It’s particularly noticeable between 70 and 85mm, where although my position and viewpoint haven’t changed, the position of the clock in the scene is slightly higher than it should be.

Nevertheless, scrolling through the images, one gets the sense of walking along the station platform toward the cafe. The subjects within the composition exit the frame with increased zoom and the effect of the image depth being reduced is clear as the focal length approaches 200mm – note the apparent reduction in distance between the rail at the end of the platform and the white sign. By using a smaller aperture, the signs and clock are acceptably sharp (while not totally so).

Reflection

A tripod would have improved the accuracy of the zoom, but that wasn’t the point of this exercise. What I’ve got from it, and by recalling and reviewing the film references in the brief, is that the image can start with one viewpoint and change to another through using zoom. As with Deckard viewing the photographs in Bladerunner, everything that is of less interest falls outside of the frame, leaving a narrow window on the subject. If used in a composition without changing viewpoint, the subject itself can be completely different. In my case, I looked at the images I shot for this exercise and saw something that amused me; the way the signs direct the viewer. For my final shot for the set, I took P4 and used a tight crop, effectively throwing away most of the frame. The subjects are now isolated from the railway platform; no longer obvious where the photograph was taken and they stand on their own in relation to each other.

What I have learned from this exercise is that although I already knew that a longer focal length creates a narrower field of view than a shorter one, zooms can be used to creatively alter what we want the image to say.

References

- Hockney, David 2012 – A Bigger Picture Exhibition Book, Royal Academy of Arts

- Johannes Vermeer and his Paintings, http://www.johannes-vermeer.org, accessed 14th December 2018